Live Encounters Poetry & Writing, Volume One, December 2020.

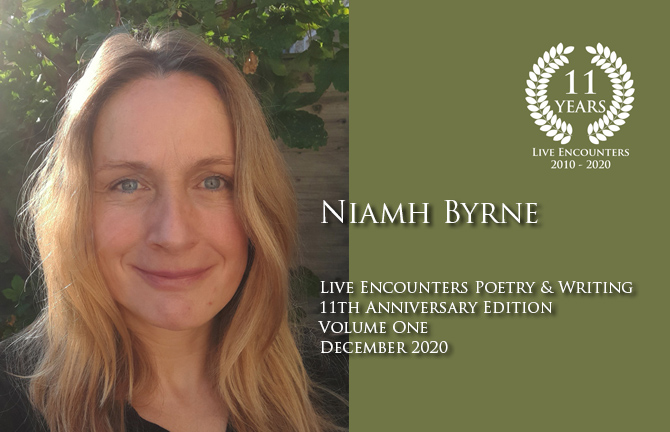

Niamh is a writer from Dublin. She has published in four collections including an Easter 1916 commemorative edition of poetry. Niamh is a member of two writing groups and regularly chairs workshops at these. Niamh has just finished her first novel ‘Ruth’ about women and war. Niamh teaches Creative Writing and has a MEd in Adult and Community education. She has performed her work at the Red Line Festival Civic Theatre Tallaght Dublin and in St John’s Theatre Listowel Co. Kerry. Most recently, two collections Niamh has published in were shortlisted for the CAP awards 2017 going on to win for Circle and Square first prize for best anthology.

https://liveencounters.net/le-poetry-writing-2017/

http://writingcap.ie/awards-2017/

https://platformonewriters.wordpress.com/

https://issuu.com/liveencounters/docs/

http://www.southdublinlibraries.ie/

https://www.civictheatre.ie/

The wind is high, the clouds a sea of pearl on a southwest tide. The clothes twist and knot on the line. The garden a wet muck, the plants limp sad cold. The sun is white bright behind the clouds. The dust catching on the window, finger prints and the paw from the cat. Inside the TV is a black screen, the stereo idle, the fireplace empty of ashes. The Christmas lights off, the dust has settled. A fine grain of it on the furniture, on the pictures, on the carpets. I opened the blinds in the kitchen delph left drying on the rack, a pot soaking in long forgotten suds. The bins nearly full, turkey and ham cooked and out on the counter. I’ll put it out for the foxes and birds. The making of a desert left in a bowl. That was a fast year I say it out loud that was a fast year wasn’t it, no one answers because there all gone on with their own lives. I ponder the pot, the dust, the delph. If I put it away what does that say? If I clean their dust what does that say? If I make that cake who will eat it? I wonder what it was the last thing they did in their own home. Was it hang out the washing, switch off the lights before bed, say I’ll make that desert tomorrow. The presents are under the Christmas tree; maybe they wrapped them and went up then to their bed. But sure, didn’t I know what the last thing was they did.

The wind is high, the clouds a sea of pearl on a southwest tide. The clothes twist and knot on the line. The garden a wet muck, the plants limp sad cold. The sun is white bright behind the clouds. The dust catching on the window, finger prints and the paw from the cat. Inside the TV is a black screen, the stereo idle, the fireplace empty of ashes. The Christmas lights off, the dust has settled. A fine grain of it on the furniture, on the pictures, on the carpets. I opened the blinds in the kitchen delph left drying on the rack, a pot soaking in long forgotten suds. The bins nearly full, turkey and ham cooked and out on the counter. I’ll put it out for the foxes and birds. The making of a desert left in a bowl. That was a fast year I say it out loud that was a fast year wasn’t it, no one answers because there all gone on with their own lives. I ponder the pot, the dust, the delph. If I put it away what does that say? If I clean their dust what does that say? If I make that cake who will eat it? I wonder what it was the last thing they did in their own home. Was it hang out the washing, switch off the lights before bed, say I’ll make that desert tomorrow. The presents are under the Christmas tree; maybe they wrapped them and went up then to their bed. But sure, didn’t I know what the last thing was they did.

If I had of dropped by … maybe; maybe I could have undone the play interrupted the set. I was like an actor waiting on cue. My belly was sour with it all. Across my ruminations of my struggle to accept betrayal, lies and deceit. Always hoping when someone is speaking that it is the truth coming from their being. I know it, I have always known. It is because I do not know how to cope with liars that I pretend to believe them. Like I pretended to believe you.

‘Ah no everything is grand, no nothing to worry about; the doctors they don’t know what they’re talking about.’

But I went, and I saw those doctors. This was too, too important; no this was life and death. I waited all day on a bench in a corridor outside their office. I stood when I saw them coming, I was invited in and told. I always know when people are lying but it’s the people I love that lie, I know what it means. This is the end they will not be in my life anymore. It’s a premonition of my future. Sometimes I’m relieved, sometimes I’m scared, sometimes I pretend but this time. This time it’s not like all the others. This time the inevitable too big for the lie. This time it’s different.

I spend the next day outside another doctor’s office; she is kinder she arrives when the nurse pages her. Yes, it is true but your Mam she signed you’re Dad out, I am sorry because I know she is not well either. Thank you doctor they just want to be together in their own home, if I could speak with someone who could help, help us for them to be together at home. The nurse makes calls; I go drink a coffee in the canteen. The nurses and doctors all eat their food and chat. An odd person sits over a coffee, I catch one of their eyes, and we nod. It is evening before we meet to make the plan of action.

‘But being the holidays; if you fill this prescription, pain relief to make them comfortable as is possible.’

I thank the social worker wish him a merry Christmas he says he has two boys waiting on Santa. I wonder if I ask Santa what would happen. I go to the church instead, there are too many people its normally empty. I light a candle anyway and I ask God to forgive me. ‘The lie’ I say ‘I know what it means can you help? Will you give your mercy?’

I leave the church and I do what needs to be done.

Afterward I eat the Christmas dinner, I pull the crackers, I drink wine, I watch a movie, and I go to bed. I dress early, I drink a long glass of water, and I close the door quietly.

Pulling into their driveway I vomit out the door onto the path, the cat walks over to it I hiss it away. My head spinning. I decide I’ll make tea I’ll bring it up to them. It’s their decision I say aloud it’s their decision, their lives. I make a pot; I put milk in the jug sugar in a bowl. The turkey and ham out on the counter cooked and ready, the makings of a desert in a bowl, delph drying beside the sink, clothes twisting on the line. I steady the tray as I walk up the stairs, their door is shut tight. I have to put the tray down and shoulder it open. I don’t look straight away. I hold onto the door and there it is. Not like in the movies when the couple are lying wrapped around each other forever embraced. No.

My mother’s leg hangs from the covers her mouth is wide open she is sideways across the bed. My father is foetal on his back like an astronaut in space; his knees face the ceiling, his mouth open his head tilted back.

I say, ‘I’ll kill the pair of yea look at you’s where you at that wine again.’

I fix my mother into the bed, I pop three pillows under her head it’s not easy Mam’s nearly hard. I can’t push my Dad’s knees down, so I sit him up and put a cushion behind him. I get an extra blanket from the hot press.

‘Now yous must be freezen, I’ll put the heater on, I have a cup of tea for yous, now a cup of tea come on now wake up.’ I put it beside them on their lockers, beside the empty wine glasses and the packs of pills. I brush their hair. My Dad’s with his comb, I fix my Mam’s wig. ‘Now that’s better.’

My bowels strangle, I run to the toilet into the sink I vomit, and the toilet fills with the sourness of Christmas. I pass their room, I can’t look their faces grey, their mouths wide open, their arms hanging from their shoulders. I get downstairs, I search my bag for my mobile. But I know I must go back up. I charge upstairs I put mams right hand under the covers my dad’s left hand under the covers and I clasp their left and right hand together over the blanket. I fold the blanket neatly and straighten it out. I turn off the heater, slightly open the small top window. I shut their door tight.

‘Ambulance please, no need to rush no, no pulse no, no heartbeat no.’

The house fills, guards wait we offer sandwiches, biscuits, tea, coffee. Autopsy, inquest is mentioned. We bury them together we play their songs, say prayers, cry at the grave go home sit and stare at the wall.

The sky is bright a southwest wind blows, the turkey and ham are wrapped now in tin foil, they came in handy for the sandwiches. I’ll put that out for the birds, for the foxes. I go and take in their clothes. Fold them put them away.

‘Who filled the prescription?’ I hear the detective’s voice in my head.

‘I did’ I say.

The room quietens; the whole family and the neighbours are looking at me. I stand taller I hold her eyes. I didn’t take my eyes from the detective’s.

‘I did’ I say again.

‘A lot of morphine on there.’

‘For the pain.’ I say.

She holds my eyes there’s just me and her now the rest fade out.

‘The social worker said it would take time for plans to be put in place, hospices and homes and such.’

She looked back down at the empty packets in her hand and the bottle of wine then looked back. I’m still looking at her.

‘And you are?’

‘I am their daughter.’

‘And you went and got all this by yourself?’

‘I did’

‘Did they ask you to go?’

‘To go?’ I say

‘To go to get the whole lot.’

‘Yes, we decided it was for the best.’

‘For the best?’

I breathe into my belly; I won’t let her look away.

‘Because of the holidays, the pain we weren’t taking any chances.’

She looks at the empty packets the half empty wine bottle.

‘They liked a good red.’

She’s looking at me again.

‘Good for them’ she says.

‘Good for them.’ I say.

©Niamh Byrne