Article in PDF (Download)

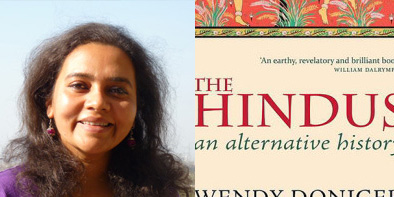

It’s my right to offend. How dare you be offended! – by Vandana Vasudevan in response to Wendy Doniger’s book – The Hindus: An alternative history

While the dust has partially settled down on the case of Wendy Doniger’s “The Hindus: An alternative history”, the controversial book which its publisher Penguin, has decided to pulp because of a legal notice against it, there are some fresh inputs that people have shared with me which prompt further comment.

In a New York Times article Doniger says that after the book was published, she and her publisher worked “to take out things we thought might be particularly offensive to Hindus, to not thumb our nose at them.” Curious choice of words, I thought. It implies that she admits that there were parts in the book which were deliberately insulting to Hindus and therefore she and Penguin sat and corrected that to some extent. “Thumbed our nose”. What a vicious way to put it. A more sincere writer would possibly say “which might hurt them” or “which might be viewed as offensive”. Thumb your nose is something bullies do in the playground to other kids when they want to show who is superior. Notice also the “our” and “them”. Them is Hindus, of course. But who is “our”? Who is this cosy team that was thumbing its nose at Hindus? White Anglo Saxon Protestants? All Caucasians? Americans? The developed world?

Writers are in the business of words and choosing the right ones usually comes easily to them, unless they are being purposely malicious or simply don’t give a hoot.

Doniger claims that the alternative history that she is presenting is that of “untouchables, animals and women.” In fact, there is less of all that and more of Wendy’s determinedly sexual perspective to fairly straightforward things and situations in a stretch of imagination that would be the envy of a fiction writer. She draws parallels between every Hindu God and his vehicle with anatomical parts. Someone needs to tell her: Wendy, sometimes a cigar is just a cigar, you know.

The details of all the fallacies in the book are described by Aditi Banerjee in an article in Outlook magazine on October 28, 2009 www.outlookindia.com and Aseem Shukla has composed a dignified retort to the book here in 2010. www.faithstreet.com

Doniger has accused anyone who dares to criticise her as a right wing fundamentalist. But there are parts which are jarring to even a garden variety Hindu like me who is nowhere near wielding a saffron flag.

For instance, take the scene in the Ramayana when Sita is alone in a hut guarded by her brother in law Lakshman while her husband Ram has gone to hunt a golden deer she desires. When they hear Ram’s anguished voice crying out their names, Sita urges Lakshman to go in the direction of the voice and help Ram. Lakshman refuses saying his duty is to guard her and Ram was invincible, so no harm would befall him. A desperate Sita then accuses Lakshman of having mal intentions towards her and of a desire to misuse the occasion of staying alone with her. Hearing this, a hurt Lakshman, of course, rushes to help his brother.

Even if someone had not read the Ramayana, just as a mere exercise in literary interpretation, a plausible explanation for Sita to utter these intemperate words would be that a stubborn Lakshman was simply not agreeing to go and in desperation she resorted to saying things which she knew would provoke him to leave her side. It is a human reaction: we all have said hurtful and exaggerated things to family members in the heat of an argument because we want to make things go a certain way and are reaching the end of our tether with the other person.

Now Doniger’s interpretation is that Sita made this comment because there existed an underlying subtext of attraction between her and Lakshman, which created a tension within the trio. And this, Doniger says, was the basis of Ram later, supporting the monkey king Sugreeva and killing his brother Vali. Vali had taken away Sugreeva’s wife and kingdom and dear old Wendy indicates that the Lakshman-Sita frisson was on his mind and seeing a parallel he felt justified to kill Vali. What is he, a character from Wendy’s favourite soap opera?

Let us pause here to allow all Hindus to hold their sides laughing or explode in fury as each may deem fit.

Moving on, she describes Lakshman’s entering into the Sarayu river, which he was obliged to do after he interrupted Ram’s parley with the God of Death, Yama, as “committing suicide”.

I cringed when I read that phrase. “Committing suicide” is not a term you would use to describe Lakshman’s act unless you deliberately want to be banal. Or you simply don’t understand the nuances and texture of Hinduism, which is definitely the case with Doniger. “Committing suicide” is the ending of one’s life because of extreme angst, hopelessness and despair. In Lakshman’s case, he merely was honouring his elder brother’s promise to Yama that no one would interrupt their closed door meeting. Since Lakshman opened the door, he came face to face with Yama, which can only mean one thing: termination of one’s earthly life. Lakshman was a divine figure, he’s not going to drop down dead like us mortals. Therefore, in complete equanimity, he steps into the Sarayu river, from where he is absorbed into heaven. It is an elegant transition, which subsequently each of his other three brothers follows. Were they all “committing suicide” then? What a crass term from a supposed scholar! It makes it painfully evident that unless you live and breathe a religion, you cannot know its warp and weft, its subtleties and tonalities just by reading books.

Everywhere, Doniger eschews the most plausible explanation and presents the most titillating one. At each juncture where a more sensitive understanding is required, she prefers to be obtuse. It is this disposition that caused her to write the most wanton description of Hinduism on Microsoft’s Encarta which was removed following this brilliant rebuttal www.sankrant.org.

And then there are her annoying attempts to be cool and funky in the oddest of places. Why a serious professor in a supposedly academic book must so frequently dissolve into flippancy and incongruous analogies from contemporary popular culture is bewildering. Sita looks at the golden deer and is “delighted that Tiffany’s has a branch in the forest” or that the monkeys in Ramayana once got drunk like a “frat party out of control”. No Indian needs these analogies. The only people who need them would be those who have no clue about the subject which makes one suspect the book is a collection of classroom lectures Doniger gave to American sophomores in the University of Chicago. (Come on, I am allowed a little guessing when Doniger is revelling in conjecture!)

Putting aside the many inaccuracies, bizarre extrapolations and meanderings into fantasy that are there in the book, two things are getting missed in the flurry of overreaction to Penguin’s decision to pulp the book.

First is the right to be offended. Just as a writer has a right to offend, a reader has the right to react in any way he or she wants. The degree of offense that is “right” to take in the view of self appointed guardians of freedom is a moot point.

While I was merely amused by the silly digressions that Doniger indulges in, someone else may be deeply hurt, another outraged. Who decides which response is valid and comfortable for everyone? To someone a Facebook post is enough, to another a 500 word blogpost is a form of protest. The man who went to court felt strongly enough to issue a legal notice. What is wrong with that- no one burnt buses or broke shop windows. Going to court is a legitimate form of expressing one’s protest. Some of our erudite commentators are bristling at the sheer act of being offended.

The second is that creative freedom, like any other freedom, cannot exist in a void. As an author I understand that the freedom to provoke, disturb and offend must be on par with the freedom to inspire, soothe and stir. But all freedoms come with responsibility.

In this book, there is no denying that Doniger has been irresponsible in her presentation of the history and mythology that shaped Hinduism, simply because she has blurred the lines between facts from ancient texts and her own fantastical interpretation of them.

In 1908, American thinker John Dewey whose work has been very influential in social thought, wrote in an essay called “Responsibility and Freedom”:

“An agent is free to act; yes, but–. He must stand the consequences, the disagreeable as well as the pleasant, the social as well as the physical. He may do a given act, but if so, let him look out. His act is a matter that concerns others as well as himself…”

When writing non fiction there is a huge onus to not mix personal interpretation with facts. This increases by many orders of magnitude when it is a scholarly work that will contribute to the work of other researchers in the field. Even more so when one is an influential academic in the world’s most influential country. And the responsibility becomes staggering when you are writing about religion because you are stepping into a very personal, sacred mind space of millions of practitioners of that religion. More so, as it happens in this case, if it isn’t your own.

——————————————-

Check out Vandana Vasudevan’s interview on her book ‘Urban Villager: Life in an Indian Satellite Town’ in Live Encounters here