Article in PDF (Download)

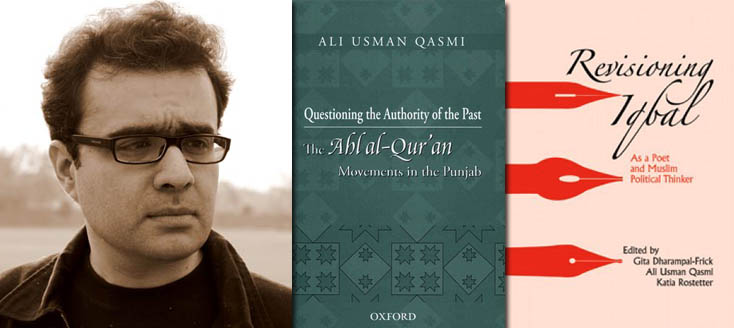

Dr. Ali Usman Qasmi, Assistant Professor (History) School of Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), on Shia-Sunni Schisms in Pakistan

The Shiite Communities of Pakistan – Brief Overview

Writing about ‘the Shiites’ of Pakistan is a difficult task for multiple reasons; To begin with, the dearth of academic literature on the history of Shiite Islam in South Asia is an impediment. An exception is the magnum opus of Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi’s two volume work titled A Socio-intellectual History of the Isna Ashari Shiʼis in India. It traces the historical evolution of Shiite communities in various parts of South Asia and maps the growth of their power and influence institutionalized in the form of political authority at different periods. The critique of this work – which is part of the second problem about academic writings on Shiite Islam – is the monolithic identity ascribed to ‘the Shiites’. It approaches the history of Shiite Islam as a linear progress towards certain ends. It gives ‘the Shiite’ a false sense of cohesive identity overlooking the fact that not only were there internal differences along class lines, the Shiites groups were devoid of necessary camaraderie, which is considered vital for any self-contained religious group. Lack of unanimity in religious ideals and doctrines had been quite tangible among Shiite.

Another problem which has been added to the corpus of writings on Shiite Islam in general is the influence of Iranian revolution since 1979. The abruptness in the fruition of the revolution propelled the Western need to make sense of the ‘Shi’i version’ of Islam with Iran being its epicentre. Therefore, most of these studies were specific to Iran and its politics underpinned by Shiite Islam, which had been played up constantly by the leaders of the revolution as a distinct feature of Iranian polity. Outside Iran where Shiite Islam did not pose a political threat, the nature of academic studies has been markedly different. For example, in case of India and Pakistan numerous studies on the ritualistic aspects of Shiite Islam were carried out by anthropologists like David Pinault and Vernon Schubel, among many others. Only recently some historians have begun to bring the historical aspects of Shiite Islam into focus with South Asian perspective. In this regard, the path breaking study by Justin Jones’ on the politics of Shiite Islam in colonial North India is noteworthy. This will soon be followed by publication of a book by Andreas Rieck on the Shiite community in Pakistan. Peter Wolfgang Fuchs, a brilliant young scholar at Princeton University is working on the history of Shiite community in Pakistan, which will soon be published. Other than anthropological interest in rituals, the origin and dynamics of sectarian violence in Pakistan particularly from 1980s onwards have drawn attention of many a scholar. In this regard the works of Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Vali Reza Nasr, Mariam Abou Zahab and Tahir Kamran are significant contributions.

After furnishing this brief overview of recent trends in the study of Shiite Islam, I will now shift my focus to different aspects of history and politics of various Shiite communities in Pakistan.

Situating Shiite Communities (within the Pakistani context)

To begin with, I find sectarian difference along Shiite-Sunni lines as arbitrary and highly problematic. In Pakistan, existence of any singular sectarian identity whether Shi’i or Sunni is a misnomer for a majority of Muslims. Both sects are riddled with internal fissures and sub-sects, punctuated at times with loyalties of class and ethnicity. Such communities exist in different locales with a distinct historical background and social ethos. But one must not lose sight of the recurrent violence against Shi’is which has brought divergent factions within the community together. The persecution has also sensitised them to the vulnerable position they are in vis a vis Sunni majority.

The Shiite communities (estimated at 15-20% of Pakistani population) are spread all across Pakistan and their social interactions with other communities and daily lives are impacted by a variety of factors. The majority of Shiites in Pakistan are Isna Ashari (or the Twelvers) with paltry number of Ismailis, Bohras and Nurbakhshi living in some parts of Pakistan.

In the Gilgit-Baltistan region, the followers of Shiite Islam have an absolute majority. Interestingly in such areas as Hunza-Nagar, they are in competition with the Ismaili denomination of Shiite Islam. In Skardu and Gance in Baltistan, approximately 25% of the population follows Nurbakhshi variant of Shiite Islam which the orthodox Shiite Ulema are reluctant to accept as a legitimate Shiite sect. The nature of violence and conflict in Gilgit-Baltistan stems from the fact that it is the only part of Pakistan where Shiite communities are in a decisive majority.

Constitutionally speaking, Gilgit-Baltistan does not form a part of Pakistan as a province. For decades its legal status remained ambivalent and some constitutional rights were extended to the region as it would have, first, influenced Pakistan’s stance over Kashmir to which these areas owed nominal allegiance at the time of partition in 1947.Secondly, if the constitutional rights are fully accorded to the people inhabiting that region it will imply authorizing ‘Shiites’ to govern, a proposition not acceptable to Sunni factions. The Sunni community has strong presence in Gilgit, the commercial and administrative centre of the entire region.

Sectarian violence leading to imposition of curfew has been a recurrent phenomenon since 1980s. For example an incident centring on the issue of textbooks in Gilgit-Baltistan published by Punjab Textbook Board led to large scale violence. Nosheen Ali’s article reveals that in Grade 7 textbook for art and drawing students were required to sketch and colour calligraphic illustrations of the names of four caliphs. This was resented by the Shi’i majority which holds a divergent view about the first three caliphs and does not accept them as legitimate inheritors of Prophet’s political authority.

The introduction of self rule in 2009 through Gilgit Baltistan Empowerment and Self-Governance Order has led to new forms of sectarian violence and insecurities. Even though this Order allows self rule, legislation and executive authority but on a limited number of issues only, it has been perceived by some radical Sunni groups as grant of power to ‘the Shiites’ to rule in a Sunni-majority country. This would imply that ‘the Shiites’ will have the authority to disallow any textbook which is contrary to the belief system of ‘the great majority’ (sawad-i-azam as some certain Sunni groups like to say in order to boast about their numbers) and implement policies in accordance with their particular belief system and liking. Such a perception has led to an increase in the scale of violence in this region. In one particular incident in 2012, a bus on route to Gilgit was intercepted at Chilas and passengers identified on the basis of ‘Shiite sounding names’ were taken off the bus and then shot dead.

In Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa the Shiites communities are concentrated in some pockets of the province and have a sizeable number in the Kurram Agency, especially among Turi and Bangash tribes. Here, Shi’i-Sunni conflict is a constant feature for many decades and is further aggravated by tribal rivalry and attempts for greater control over water and other natural resources as the region has limited sources for livelihood.

In Balochistan, Shiites are less significant in terms of numbers. Some commentators have tried to essentialise this on the basis of historical rivalry between Iranians and Baloch. The poetry about mythical origins of Baloch suggests that the Baloch clans lent support to Imam Husain in Karbala and were consequently punished for this support. The result was the mass exodus of Baloch from Halab or Aleppo (currently in Syria). A Baloch nationalist historian, Inayatullah Baloch, maintains that the Baloch people embraced Sunni Islam in reaction to Safawid Iran’s acceptance of Shiism. In present day Balochistan, the Shiite communities like Hazaras, who migrated from Afghanistan, are mostly settled in Quetta. In recent years, Hazaras have been subjected to the most atrocious violence in which thousands of their men women and children have been exterminated. In 2012, the Hazaras registered a powerful protest in Quetta by organizing a sit-in in freezing temperatures with un-buried dead bodies of those killed in a massive bomb blast. It was only after this protest that the provincial government was dismissed and governor rule imposed in the province. Some commentators have suggested that Hazara carnage was not just sectarian in nature but it also had ethnic dimension in which non-Pashtun and non-Baloch groups were being targeted. Some have also alluded to the involvement of property dealers of Quetta who benefit from forced or panic eviction of ‘non-residents’ of Quetta as they sell off their properties at reduced prices to escape violence.

In Punjab and Sindh, the Shiite communities are not concentrated in any particular area but spread across the region. The local culture emblematic of the spiritual bonds and connections with Sufi shrines spread throughout the region, present a highly syncretic picture. The Sufi shrines serve as pluralistic sites of interaction between people of different ethnic and religious backgrounds. In the case of present day South Punjab and Sindh, the Ismaili missionaries remained active for hundreds of years and even managed to establish their rule for some time. The effects of that resonate even to this day in centrality of the figure of ‘Ali’ as a spiritual fountainhead. Reverence for Ali and Ahl-e-Bait holds the sway with majority of inhabitants in the region maintaining allegiance to Sunni Islam.

However, it will be too simplistic to presume an idyllic co-existence between the sect(s), devoid of any conflict in this sprawling region. Since the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, this area underwent a revivalist streak which profoundly influenced some of the Sufi orders; Chishtis in Punjab being a case in point. Another influence has been spawning of the reformist Islam from late nineteenth century onwards, which professed and upheld unequivocally the puritan version of Islam, devoid of any local cultural influences. The legacy of the reformist Islam was sustained through the mushroom growth of the number of madrassas. The number of madrassas continued to multiply after 1947. It acquired a steep growth gradient during 1980s as petro-dollars from Saudi Arabia and Sheikhdoms started pouring in. The petro dollars were funnelled into, first, to strengthen the political and religious influence of a more ‘Arabized’ Islam in Pakistan and, second, to provide finance for a proxy war against a resurgent Iran, who itself was bent on spreading its version of revolutionary Islam in the region. These madrassas not only provided education but also food and shelter to some of the most deprived segments of the population. Equipped with the power to speak authoritatively about Islam, passionately invoke rhetoric and provided with funds to acquire sophisticated weaponry, some of these madrassa trained students laid the basis for wholly new brand of radical religious violence in Pakistan. Previously, there had always been disputes on such issues as tazia processions and polemics about the veracity of one’s sect over the other leading to occasional skirmishes and even limited scale violence as well. But what Pakistan witnessed from 1980s onwards was unprecedented. In his influential essay on the origins of sectarian violence in Jhang – which became the epicentre of such trends in the entire Pakistan for decades to come – Tahir Kamran has done an excellent social profiling of Haq Nawaz Jhangawi, the founder of rabid anti-Shiite militant group called Sipah Sahaba Pakistan (The Army of the Companions of the Prophet). Jhangawi came from a poor tenant family working for a local landlord who was a Shiite. Once Jhangawi had been madrassa trained, he became a fiery speaker equipped with the ability to inspire and enthral his audience with hateful speech against local Shiites. With his financial resources expanding, Jhangawi inverted the power relations between him and the Shiite feudals. This subsequently served as a model not just for Jhang but for several parts of South Punjab where there were numerous ‘Shiite landlords’ and ‘Sunni tenants’ who could find similar inspiration and finances from madrassas.

Karachi represents an interesting medley of various Shiite communities. Not all of these communities are followers of Isna Ashari variant of Shiite Islam. Various Bohra and Isamili communities also wield considerable influence because of their entrenched prowess in industrial and financial sectors. Most of the Shiite communities of Isna Ashari persuasion came to the city as migrants from United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh in India) in 1947 and brought with them various regional varieties and traditions pertaining to Muharram rituals. Consequently Karachi came to be the most important centre of azadari in South Asia where different traditions and rituals are devoutly observed during Muharram. As an upshot to the Shii concentration there, Karachi became a centre of sectarian violence for many decades. From 1990s onwards targeted killing has become a norm; hundreds killed were identified as ‘Shiite doctors’. In addition, Imambargahs and tazia processions were at times sabotaged by suicide bombers.

The Interests of the Shiite Communities

At the time of partition, the Shiite communities of the areas which constituted Pakistan in 1947 were less significant. Their numbers and influence was greatly enhanced by the influx of migrants from United Provinces. These migrants were more affluent and educated than most in the existing communities.

During the early decades of Pakistan’s history, various Shiite organizations that cropped up attempted to impose an ‘all Pakistan’ tag and petition the government on the behalf of ‘the Shiites’. Their demands were mainly focused on issue of permits for tazia processions, recognition of the right of Shiite communities to practice azadari and, later, demand for the inclusion of ‘Shiite Islamiat’ at school level. While Shiite rituals and their practice was a recognized feature even during the colonial period and hence continued in Pakistan as well without any hiccup, the demand for ‘Shiite Islamiat’ however was a new one. Various Shiite organizations complained about their children being instructed in a version of Islam which was completely at odds with Shiite beliefs. Hence they demanded that Shiite students should have the option to study Islamiat as approved by Shiite scholars. This demand finally got the nod of approval during Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s government in 1974. But Shiite Islamiat was introduced at high school level only. It never became popular with students as, in many cases , government schools did not have qualified teachers to teach it. Also, students were not too keen to distinguish themselves along sectarian lines by opting for Shiite Islamiat and, hence, make themselves prominent or subject to discrimination and even violence.

A wholly new dimension was added to the politics of Shiite organizations by the Iranian revolution of 1979. Iran became a Shiite republic. It was all the more eager to export its brand of revolution in the region. It also championed the rights of Shiite communities around the world. For this purpose, various Shiite organizations were supported and financed by Iranian government. The Iranian version of Shiite Islam – including the concept of vilayat-i-faqih –was widely propagated. The main interest of this new brand of Shiite organizations was to transform Shiite communities from a quietest group of mourners to a politically charged one. For them Karbala did not simply have a moral, pietistic and spiritual significance rather it represented a clarion call for political action. They, therefore, sought to go beyond rituals like self flagellation or matam. This was argued on the ground that it makes Shiite Islam ‘look bad’ to an outsider. Alternatively, they suggested setting up blood banks where mourners could donate blood on the 10th day of Muharram instead of ‘wasting’ it by self flagellation.

It is difficult to estimate the strength and impact of these new groups and organizations. In his important article on this theme, Hussain Arif Naqwi points out growing differences in Shiite communities. Many in Shiite communities have resisted this Iranian version of Shiite Islam. But the influence of Iran has continued to wax because of its generous financial support for the construction of madrassas and scholarship awards to potential candidates for pursuing higher studies in the prestigious centre in Qom. The dialectics of this struggle – which is partly played out in competing understandings about the trope of Karbala – continues to unfold and will have an important bearing on Shiite communities across Pakistan.

Lastly, the issue of security is deemed extremely vital, given the spate of violence against Shiites in Pakistan. For extremist Sunni groups, every Shiite is a potential target. In many cases the Shiite as a target can be identified on the basis of his/her name and artefacts of religious symbols carried by them. The Shiite communities all over Pakistan bear the brunt of this indiscriminate violence. In places like Parachinar, there is no let up in the violence against Shiites for years. Killings in Dera Ismail Khan go unnoticed because of lack of media reporting and general lack of security in the region. A lull in the bombings of Hazara residential areas in Quetta is temporary as those perpetrating violence are not brought to justice. Gilgit remains prone to violence throughout the year. ‘Target killing’ of members of the Shiite community is ubiquitous in Karachi too. More recently, disturbing trends have emerged in Punjab and rural Sindh as well. In case of latter, mushroom growth of madrassas belonging to more radical Sunni groups has heightened the sectarian tensions in areas like Sukkhur and Nawab Shah. Large scale target killing of Shiites used to be a common phenomenon in Punjab during 1990s. The fact that the once defunct Sipah Sahaba Pakistan has become active and been allowed to operate – at least in South Punjab – there is a growing sense of fear that the saga of 1990s will be repeated.

Some commentators have suggested that there is a silent agreement between Pakistan’s Punjab-centric military establishment and sectarian militants whereby the militants have been allowed to keep their presence in the marginalized South Punjab which also serves as a happy recruiting ground (for Lashkars) in the most impoverished areas and carry out their actual operations elsewhere in Pakistan. Such an ‘arrangement’ can quickly go out of control as was evident in a recent incident of violence in Rawalpindi on Muharram 10th during the tazia procession. In that incident, a mosque and madrassa with links to a radical Sunni group was torched and students lynched. This led to massive unrest in the city and curfew was imposed for a couple of days. Other cities in Punjab also experienced hyper sectarian tensions. This incident calls for a more nuanced understanding, an understanding that may help us get to the root of the violence which rocked Rawalpindi rather than simply analyzing it along essentialized Sunni and Shiite identities. This is what I have tried to achieve in this article by advocating a move away from singularity of identity and emphasizing the variations within the Shiite communities, coupled with a focus on socio-economic milieu to explain factors that contribute to sectarian violence.

References

Ali, Nosheen. “Outrageous state, sectarianized citizens: deconstructing the ‘textbook controversy’in the Northern Areas, Pakistan.” South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 2 (2008).

Ali, Shaheen Sardar, and Javaid Rehman. Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Minorities of Pakistan: Constitutional and Legal Perspectives. Routledge, 2001.

Baloch, Inayatullah. The problem of” Greater Baluchistan”: a study of Baluch nationalism. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden, 1987.

Jones, Justin. Shi’a islam in colonial India: religion, community and sectarianism. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Kamran, Tahir. “Contextualizing sectarian militancy in Pakistan: A case study of Jhang.” Journal of Islamic Studies 20, no. 1 (2009): 55-85.

Naqvi, Hussain Arif, “The controversy about the Shaikhiyya tendency among Shia ‘ulama in Pakistan”, in: Brunner, Rainer, and Werner Ende. The Twelver Shia in modern times. Brill, 2001.

Pinault, David. The Shiites: Ritual and popular piety in a Muslim community. St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

Rieck, Andreas T. The Shias of Pakistan: An assertive and beleaguered minority. Hurst, May 2013.

Rizvi, Saiyid Athar Abbas. A socio-intellectual history of the Isnā ʼAsharī Shīʼīs in India: 2 Vols. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1986.

Schubel, Vernon James. Religious performance in contemporary Islam. South Carolina University Press, 1993.

Zahab, Mariam Abou. “The regional dimension of sectarian conflicts in Pakistan.” Pakistan: Nationalism without a Nation (2002): 115-128.

———————————-

Dr. Ali Usman Qasmi is Assistant Professor (History) at the School of Humanities, Social Sciences and Law since January 2012. He received his PhD from the South Asia Institute of Heidelberg University in March 2009. Before joining LUMS, he was a Newton Fellow for Post Doctoral research at Royal Holloway College, University of London. He has published extensively in reputed academic journals such as Modern Asian Studies, The Muslim World and The Oxford Journal of Islamic Studies. He has recently published a monograph titled Questioning the Authority of the Past: The Ahl al-Qur’an Movements in the Punjab (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2011). Besides these, he has co-edited a volume on Muhammad Iqbal titled Revisioning Iqbal as a Poet and Muslim Political Thinker (Heidelberg: Draupadi, 2010; Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2011). Dr. Qasmi is also a visiting research fellow in History at the Royal Holloway College, University of London.

http://www.anthempress.com/the-ahmadis-and-the-politics-of-religious-exclusion-in-pakistan

http://oup.com.pk/shopexd.asp?id=2106

http://oup.com.pk/shopexd.asp?id=2010

Twitter @AU_Qasmi

One Reply to “Dr. Ali Usman Qasmi – Shia-Sunni Schisms in Pakistan”