Article in PDF (Download)

Crossing the Bridge to the Past: Reflections on Damascus, Syria

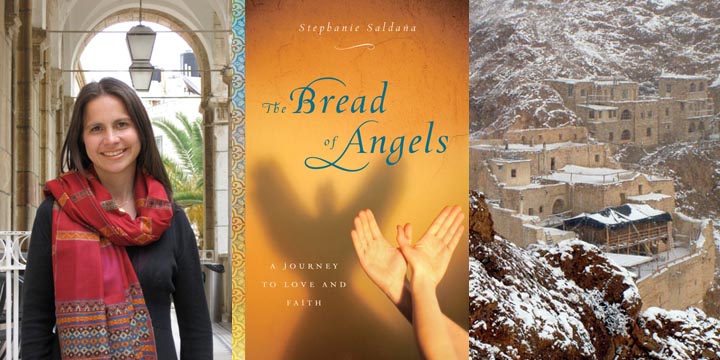

Stephanie Saldaña author of The Bread of Angels

L.P. Hartley famously wrote that “the past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” When I set out to write this piece, a friend of mine mentioned that I was sitting down to do the unenviable task of writing myself into the story of my own past. And while I agree that the past is a foreign country that all of us are in some way exiled from, in this case it is even more true, for the past I wish to write about is a world that I used to live in that no longer exists. I am writing about Syria: a country that I loved and that changed my life forever, and which is now in its third year of a devastating civil war. Never has the past felt so much like a country where things were different, and that now has disappeared.

In 2004, when I was twenty-seven years old, I finished my Masters at Harvard Divinity School and set out to spend a year in Damascus, Syria, on a Fulbright fellowship to write about the Prophet Jesus in Islam. As a scholar of Christianity and Islam I knew that Damascus was one of the richest cities in the world in which to study Muslim-Christian dialogue, a place where Muslims and Christians had lived side by side since the earliest days of Islam, and where Arabic speaking Christians were still a thriving minority, forming one of the oldest Christian communities in the world. The Syrian landscape was a living testimony to a Christian past, studded with the ruins of monasteries from the Byzantine Empire. The Umayyad Mosque, which sat like a jewel in the heart of the old city of Damascus, with a towering minaret known by locals as the “Jesus minaret”, was once the cathedral of St. John the Baptist, and remained a site of Christian pilgrimage. Tradition held that in the earliest years of Islam, Muslims and Christians had shared the space, each praying in their own respective section.

I had traveled to Syria several times in the past, and I had always wanted to return there for research. Yet while I justified my journey in scholarly terms, in ways I was only beginning to understand I was really running away: from a broken heart, from a family history of depression and madness, and from a life in which I had found myself, despite my years in Divinity School, somehow exiled from God. The following twelve months, which I write about in my memoir The Bread of Angels (Doubleday, 2010), would see me wrestle with God, with myself, and with everything I imagined my life would become, at times losing nearly everything.

When I arrived in Damascus that summer, I had nothing more than the two black, wheeled suitcases I brought with me from Boston, and a map of the city to help me find my way. I set out to search for a house in the only way that I could think of: by knocking door to door in the ancient Christian neighborhood of Bab Touma, where locals sometimes rented rooms out to students. It was the height of the U.S. led- war in Iraq, and perhaps not the smartest moment for an American girl to go knocking house to house in Damascus, Syria. Yet eventually I found a room in a sprawling, enormous house just off Straight Street, the famous street where St. Paul fell from his horse after being blinded by a vision of Jesus. My neighbor, a 73-year old Armenian who called himself The Baron, quickly adopted me, insisting that I drink tea with him at least three times a day and commenting on everything from my clothes to my desire to study Islam. There was no way that I could know that he would not only be my neighbor but that he would become my home: that he would teach me about war and about survival, and that, most of all, he would teach me to speak the Syrian dialect of Arabic.

The Baron had lived through the Lebanese Civil War, and in his past life—before he lost his entire fortune— he had been a shoe salesman. Though he was now very poor, in the afternoons he entertained me with tales of his old life, stories of wooing women and selling shoes, playing football and traveling to Milan and Tehran. After I finished listening to his stories, I wandered into the narrow streets of the famous Old City, the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world, and found myself in a world more diverse than I thought possible, where Armenians, Kurds, Sunnis, Shiites, Iraqis, Circassians, Palestinians, and even a few Jews lived, and where it didn’t seem surprising that my Christians neighbors still spoke Syriac, a dialect of the Aramaic language Jesus once spoke. In the early evenings I would enter the Umayyed mosque and watch pigeons circle the Jesus minaret. As the sun set, the courtyard was magically transformed into a river of light, so that the children playing in it seemed to be illuminated.

Those moments of light illuminated the darkness, and yet the darkness remained. I was an American in Damascus during the height of the U.S. led invasion in Iraq, and the tension was palpable. I could not enter a taxi without the driver grilling me about American foreign policy, which I stumbled to discuss in my failing Arabic. In my language classes at Damascus University, America was a common topic. Secret Police were everywhere. In fact there was nothing secret about them, and they came to my house off Straight Street and openly questioned me. In the meantime, the streets of the Old City flooded with refugees fleeing the war in neighboring Iraq. With tensions rising between the American government and Syria, many of my neighbors feared that they, too, would be invaded. I, too, was scared.

In November of 2004, George Bush was re-elected as president of the United States, and it quickly became clear that the war was only going to get worse. That week, I packed my bags, and headed to the desert to change my life.

It was not just any desert, but the ancient monastery of Deir Mar Musa, a stunning 6th century monastery hanging from a cliff face and accessible only by a flight of 350 stairs. I was there to meet Paolo Dall’Oglio, the Italian abbot of the monastery, who had invited me to do the month long Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, a month of silence and meditation. During that month, I would be asked to confront all of the demons of my past, and to meditate on the gospel of Matthew. Finally, I would need to make a decision about what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. I had no idea of what that choice would be. All I knew was that something had to change.

When I reached the top of the stairs, Fr. Paolo was waiting. I had never met anyone like him, with his voice booming across the courtyard. He was imposing: six foot four, with an unruly beard and enormous hands, a burly Roman who looked more like he belonged on a rugby pitch than in a monastery. Completely fluent in Arabic and yet constantly gesturing with his hands like an Italian, he had first come to the monastery in 1982, when it was still in ruins, and decided to rebuild it into a monastery dedicated to dialogue with Islam. Every year, alongside Christian pilgrims, thousands of Muslims climbed the stairs to visit with the local community, where they would eat and even pray. Though Paolo was a devout Christian, he believed that Islam was part of his own spirituality, that Islam was not an accident, but part of God’s plan for the world. He did not think that mere co-existence between Muslims and Christians was enough, but he believed in dependence: that the Muslims and Christians of Syria needed one another to be whole. He even named his desert monastic community Al-Khalil, the special name that Abraham, the “friend of God” and father of Muslims, Christians and Jews, is given in the Quran.

For an entire month, in the silence of the mountains and the desert, I prayed. In the tradition of the Spiritual Exercises, I meditated on the stories of the gospels until I could picture the characters in front of me, could ask them questions and wait for them response. I remembered what a priest had once told me, that you know that you are really immersed in the Exercises when the characters start telling you things you don’t want to hear! And they did. And yet the spirituality of my childhood, that I had been exiled from so long, came back and lived beside me, day after day in the desert where monks had come to pray for 1500 years.

In the evenings I came and sat across from Fr. Paolo, and we spoke of my past, of my fears, and of my hopes. He spoke to me of fear as a gift, something to be confronted, as something that always comes to us on the way to faith. This is why, in both the Old and New Testaments, angels always appear and whisper: “Do not be afraid.” For fear comes when blessings come. I listened to him, and in a way that has happened in monasteries around the world since the beginning of Christianity, Fr. Paolo became a spiritual father to me, listening to me, until day after day I slowly climbed my way back to God. By the end of a month in the desert, not only had I reconnected with my faith, but I had decided to become a nun.

Yet as the saying goes: man makes plans, and God laughs. In the months following the Spiritual Exercises, I returned to Damascus, became ill, and lost faith again. This time I was nursed back by the unlikeliest of people; a famous female Sheikh by the name of Huda al-Habash, a teacher renowned for her deep knowledge of the Quran. In Damascus, at a young age, she had founded the city’s very oldest Quranic school for girls, where hundreds of girls came to memorize and study the Quran. Though she knew that I am a Christian, she invited me into her home to study the Quran with her, and together we explored the Quranic verses on the Virgin Mary. With her I read about a Mary who is young and alone, and who is one day asked to carry a burden that seems almost to heavy to bear: to give birth to Jesus. She wanders into the desert in labor, at one moment so despondent that she wishes that she could die. And then she has the child.

Day after day I studied and recited the verses of Mary from the Quran, amazed by her story. Here was resurrection in the story of a young girl: life coming in the midst of despair. Those weeks, I recited the Quran with my female Sheikh, and slowly became well again. I drank endless glasses of tea with the Baron, my Armenian neighbor. I befriended my neighbors, in particular an Iraqi refugee named Hassan, a poet who taught me that poetry exists everywhere, even in the midst of war. I fell in love with the Syrian dialect of Arabic. And I discovered that the resurrection I had been searching for in a monastery in the desert was all around me, in the dirty, mad, tense, and beautiful streets of Damascus. I was made new, in the place I least expected it to happen.

That was ten years ago. When I set out to write a memoir, The Bread of Angels, I thought that I was simply capturing in writing a year that changed my life forever. For Syria did change my life: I found a home, I found God, I found two spiritual teachers. I fell in love with a country. Before the end of my time there, I would meet the man I would marry.

Yet The Bread of Angels will now be remembered for something I never intended: for capturing a world just before it disappeared. For as we know now, that incredible diversity I experienced in Damascus, that world where Sunnis and Shiites and Alawites and Kurds and Christians lived side by side, was a thing of magic when it worked. But the moment in which it did not, that very diversity became a tinderbox for civil war.

Though I left Syria in 2005, I never left completely. Fr. Paolo remained my spiritual father for the next ten years. When I married instead of becoming a nun, he flew to Europe to say the wedding mass. When I had children, he traveled to Europe to meet them. A nun from the monastery is my son’s godmother. Fr. Paolo and I remained as close as two people can be who are not family, our destinies tied to one another forever during a month of silence and prayer in the desert.

Yet I could never have known a decade ago what would happen to him and the country he had grown to love during the more than 30 years he made it is home. As the Syrian Civil War began to take shape, and as civilian casualties began to mount, Fr. Paolo increasingly became critical of the Syrian government. Eventually, he was forced into exile. Yet rather than stay away, he began to sneak in and out of the country illegally, visiting those in the north most affected by the war, and even negotiating the release of kidnapped citizens. I last spoke to him on Skype in July of 2013. He was calling me to say goodbye, for he was going again into Syria, this time on a dangerous mission. When we spoke, we talked about hope in the midst of despair, hope “the size of a mustard seed”, the smallest of the seeds, able to give birth to the largest trees. It was a hope that could grow and give root even in the midst of war.

Two weeks later, he entered Syria to negotiate for the release of kidnapped prisoners, and was kidnapped himself by ISIS, an Islamist militant group associated with Al-Qaeda. No one has heard from him since. When I think of him now I think of hope, of a tiny seed—the size of a mustard seed—planted in the desert.

My female sheikh, Huda al Habash, also went into exile shortly after the war began. I watched videos of young girls I knew from her mosque, many of them teenagers, marching as gunfire sprays in the background. I do not know when I shall see her again. Nor do I know where my old neighbor, the Baron is: though I have watched news of bombs going off near my old house, where St. Paul was thrown from his horse. Just as I have watched news of nearly every neighborhood I walked in being bombed. Even the Iraqi refugees I know have returned to Baghdad, where it is safer than the Damascus where they once sought refuge.

The monastery of Deir Mar Musa is largely empty, the monks and nuns in great danger isolated in the desert. In a nearby church, hundreds of families, most of them Muslim, have sought shelter, all of them fleeing violence and seeking food and warmth during the cruel winter. The villages I knew around the monastery have been the sites of some of the fiercest fighting of recent months, in a war that has now taken an estimated 130,000 lives. Barely a week goes by when I don’t learn of a place I once knew that has now been destroyed: a city street, a market, a church or mosque. Recently I saw a picture of a bridge collapsed into the water, and it took me a moment to remember that I had stood on that bridge, that very bridge, collapsed into water.

If I am glad that I wrote The Bread of Angels it is to remind myself, and perhaps others, that a different Syria once existed— no, that it exists still, somewhere under the rubble of war. Somewhere beneath this madness is a country that welcomed a stranger, a girl alone, from an enemy country, and embraced her and gave her a home. Surely this place still exists, of only in the hearts of those who once made it so—surely there is resurrection, even in the midst of these horrors—there must be. I will never give up hope that the shattered bridge will be recovered from the waters, and rebuilt, and we will cross it. Until then, I am glad to share the lessons and stories of friends, my neighbors, and my beloved teachers—one Christian, one Muslim. May we at least meet in these pages, and say: we are so very blessed, so lucky to know you— if only for a moment. Inshallah, we will meet again.

———————-

Stephanie Saldaña is an author and Lecturer in Literature at Al-Quds Bard College in the West Bank. She has lived in the Middle East for much of the last thirteen years, where she has worked extensively on Muslim –Christian dialogue, with a focus on Syria. She has worked as a journalist in Lebanon, and was a Fulbright Islamic Civilizations scholar in Syria. Her book The Bread of Angels, a memoir of her experience in Syria, was released by Doubleday in 2010, and she is currently at work on her second book, entitled The Country Between.

This is truly beautiful. ‘For fear comes when blessings come.’ I have written that down. Thank you.