Article in PDF (Download)

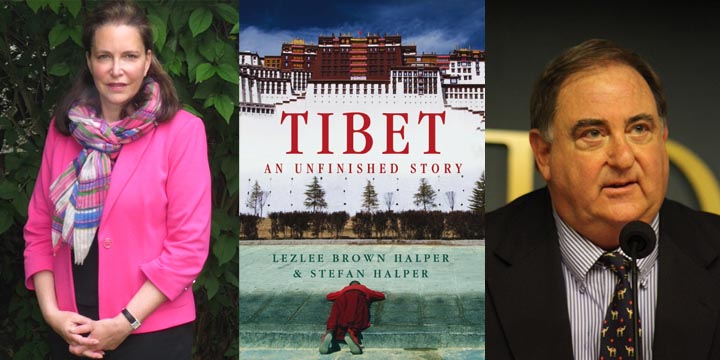

Dr Lezlee Brown Halper and Dr Stefan Halper authors of TIBET – An Unfinished Story

(Hurst Publishers) in an exclusive interview with Mark Ulyseas

Have you travelled to Tibet?

Yes, we have travelled to Tibet on several occasions between the 1990’s and 2008, staying in Lhasa and surrounding areas. We have also made multiple visits to China with stays in Xian, Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu, Wuhan, Guangzhou, Urumqi, Ulaanbaatar, Hohhot, Hong Kong and Macau, and Xingjian province.

Could you give us a detailed overview of the book?

Our book is the story of two Tibets. In the first instance, there is the story of Tibet’s dramatic quest for independence, which proceeded amidst the treacherous politics of the Cold War. Here, a small insular and naïve government in Lhasa sought help from India, Great Britain and the United States in repelling the 1950 People’s Liberation Army (PLA) invasion. Instead, Lhasa encountered a perfect storm: on one side an aggressive new China was determined to absorb the Buddhist Kingdom; on another was Nehru, who believed India’s security required good relations with Beijing. Then there was Britain, whose financial straits severely limited an on-going role; and finally, the United States was constrained by its alliance with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and the China Lobby in Washington, both of whom believed Tibet was part of China, not to mention its broader preoccupation with the USSR.

In a second dimension, we describe another Tibet. It is the story of the Tibetan myth—the longest standing myth in the West. It provides Tibet with a form of ‘soft power’ that has much to do with how China is seen in the world today.

Beijing’s vigorous attempts to suppress the Tibet story have, in effect, helped to sustain it. For some, the story is a morality play about the failure of force to subdue the human spirit, and for others it is an inspirational fantasy embracing the ideals of peace, wisdom and rationality, shrouded in the Himalayan fastness.

Like the Himalayan mist, the story drifts across ‘The Great Wall’, defying Beijing’s formidable censors. It cannot be suppressed, or prized from the world’s imagination, or set aside. This Tibet occupies a special place in the West. And it is the power of the myth that has anchored the Tibet story in the public mind today.

We first heard of Tibet from Herodotus, whose tales of gold-digging ants seized the European imagination for centuries to come, in the fifth century. Then, there was Odoric of Pordenone, a fourteenth-century Dominican Friar whose riveting descriptions of wine, women with teeth as long as boar’s tusks, and sky burials brought further mysterious and compelling images to the West.

In 1904 Sir Francis Younghusband, in service to Victorian England, opened Lhasa to the West. And though the experience began for Younghusband simply as part of the ‘Great Game’, he returned home to a spiritual life following an epiphany in the silent mountains outside Lhasa.

In 1933 James Hilton published the memorable book, Lost Horizon. He adroitly combined Tibet’s most arresting images—the telepathic powers of the lamas, the promise of eternal youth, a measured, rational life, the mystery of the high Himalayas, and, of course, the gold-digging ants—in a brilliant depiction of the place he called Shangri-La. His book was an international bestseller; Shangri-La quickly became a part of the vernacular.

The 1930’s also saw one of the more bizarre episodes in Tibet’s journey through Western culture. In 1939 Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, guardian of the Nazi myth, dispatched an expedition consisting of anthropologists, sociologists and ethnographers in hopes of finding the roots of the Aryan race. The book covers this in some detail.

President Franklin Roosevelt, who had read Lost Horizon, was enamoured with Shangri-La. On selecting his new presidential retreat in the Catoctin Mountains near Washington he said: ‘This is Shangri La’. (It was later renamed Camp David after President Eisenhower’s son.)

And finally, we hear about Tibet from Mao Tse-tung, whose Red Army invaded Tibet in October, 1950. The Chinese Foreign Ministry archives reveal that he warned that Tibet needed to be subdued quickly because its special place in the West might lead to American or British support for the resistance. And, of course, Mao was right.

Harry Truman, enunciating what would be called the Truman Doctrine in March 1947, was heard by oppressed peoples around the world, including the Dalai Lama. It committed the United States to support, in principle, those whose freedom was threatened from both external sources and internal subversion, but did not commit the US to assist every resistance movement in all locations at all times.

Thus, if the question is why Washington supported the Tibetan resistance, but not the Basques, Kurds or Sri Lankan Tamils, the answer is that Tibet combined geopolitical logic with America’s liberal internationalist ideals. The US thought it possible to limit communist expansion while recognizing the determination of the Tibetan people to pursue their traditions and religion against all odds.

Despite domestic and diplomatic constraints, the book describes how Washington mounted one of the great Cold War clandestine efforts. Hundreds of Tibetan resistance fighters were trained in the ‘black arts’ at bases in Saipan, Colorado and Nepal to resist the PLA occupation. Yet the Chinese grip remains. The results of China’s invasion, now in its seventh decade, have been tragic for both Tibet and China. While Beijing remains determined to deconstruct Tibet’s unique culture, China’s brutality is condemned on the global stage. The result has been the questioning of China’s civic culture and values and the retardation of China’s hopes for global leadership. Tibet has become the poster child for China’s human rights record.

It appears that countries around the world support an ‘autonomous Tibet’. The term ‘independent’ is not in vogue. Even many Tibetans speak of autonomy but never ‘independence’. Is this an acceptance of China’s claim to the region and, in effect, giving legitimacy to the occupation?

The concept of ‘independence’ and man’s aspiration to freedom will always be with us. Subjugated peoples seeking national independence are found in every corner of the globe. Tibetans have not, until recently, used the word ‘independent’ because the word did not exist in the Tibetan language. Tibetans historically believed they were autonomous and separate from China—hence there was no need for the word ‘independent’. Non-use of the word in Tibet certainly does not denote acceptance of China’s claims or imply that China’s invasion and occupation are legitimate. The word is not used inside Tibet today for the obvious reason that to do so would invite a prison term. The Beijing authorities do not tolerate the use of the terms ‘autonomy’ or ‘self-determination’ because they believe acceptance of these would constitute a step towards independence.

Despite the material benefits for some Tibetans under Chinese rule, hot water and public transport are inadequate substitutes for culture and religion. This point is underscored by the fact that Chinese troops patrolling Lhasa carry both fire extinguishers and firearms in hopes of limiting further desperate protests by self-immolation; there have been 126 since 2009. China is unable to explain these extreme acts of resistance to its occupation, and is embarrassed by the accompanying global condemnation.

India has developed permanent political inertia on the Tibet issue. Is this because it has border issues with China, and the burgeoning Indo-China trade between the countries supersedes the question of the occupation of Tibet?

India’s political posture is better described as realpolitik than inertia. Since 1947, when India obtained its independence from Great Britain, the Indian government has been acutely aware that its 2000-mile border with China presents a serious challenge to Indian security. The People’s Liberation Army invaded India in 1961–2 and occupied areas of northern India for several weeks before withdrawing. China continues to occupy the Indian-claimed province of Aksai Chin and claims the northeastern Indian province of Arunachal Pradesh, which Beijing calls ‘South Tibet’.

Though memories of the war, now a half-century ago, continue to resonate in Delhi and along the northern border provinces, trade between India and China resumed in 1978, reaching a value of $51.8 billion, making China India’s largest trading partner. Bilateral trade is thus a priority concern and outweighs India’s interest in Tibetan independence. That said, India hosts the Tibetan government in exile located in Dharamsala and provides a range of social services to its supporting population of some 35,000. Moreover, the Indian people often express sympathy and support for their Tibetan Buddhist ‘cousins’.

Why is Tibet referred to as a Buddhist country when in fact it was BON that was widespread as late as the seventh century? And why does the Dalai Lama speak for all Tibetans even those who are not Buddhists? Is the Dalai Lama the de facto head of Tibet?

BON was not, in fact, an organized religion. The word originally referred to a priest or ritual. As Buddhism took hold in Tibet, BON rituals developed and became incorporated into Tibetan Buddhism in the seventh century. Buddhism became a major presence in Tibet by the end of the eighth century. The Dalai Lama is the head of Tibetan Buddhism known as the Gelug school (or Yellow Hats). Most Tibetans today practice Buddhism and they view the Dalai Lama as their leader.

Prior to the Chinese invasion and annexing of Tibet, what were the rights of the ordinary Tibetans? Was it ruled by ‘elite’ Buddhist monks or a democratically elected government?

Prior to the Chinese invasion, the head of the Tibetan government was the Dalai Lama, who had final authority on policy and personnel decisions. Historically, when the Dalai Lama died a regent was appointed until the young leader took power. The Tibetan government was not democratically elected and most governmental positions did not require specific training. Indeed, like other pre-modern societies, many people remained in government positions until they died or retired. While many were promoted based upon their abilities, it was also common for people to be appointed to positions based upon friendships or loyalty to the leadership.

Most policy and personnel decisions were resolved by the Kalon Tripa, an official who functioned as a prime minister and reported directly to the Dalai Lama. The Kalon Tripa oversaw the Kashag—or administrative power—consisting of four officials (kalons): three were lay officials and one was a monk official. The Kashag was considered to be the administrative centre of the Tibetan government and coordinated a range of bureaucratic functions, including the Finance Office.

The rights of ordinary Tibetans are discussed in the answer to the next question.

The Chinese have claimed that when they ‘liberated’ Tibet from the Dalai Lama and his followers they discovered that the monasteries practiced serfdom—slaves working the land for the monasteries without pay or any rights. Is this true or merely propaganda?

In the summer of 1950, Beijing broadcast propaganda announcements in Tibetan to Lhasa on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. The theme normally centred on the promise that Tibetans would be ‘liberated’ and would be ‘reunited with the Motherland’. Here Mao Tse-tung’s government referred to ‘liberating’ Tibet from the British and the Americans. The notion of liberating Tibetans from ‘feudalism’ as a propaganda theme began about six years later. Today this theme has evolved and now emphasizes Tibetan backwardness, insularity and the importance of modernization through China’s guidance.

Like the rest of the pre-modern world, including vast stretches of Asia and China itself, Tibet was a traditional society with various and complex relations between the population and the land and landowners, including the monasteries. The incoming Chinese government espoused a radical Communism that would soon institute collective farms that brought famine and death to some 40 million people in China from1958–1962. It had a clear political, ideological interest in demonizing the monasteries and the land system extant in Tibet. History and propaganda do not mix and certainly didn’t in this case. Chinese propaganda has a political purpose; it is designed to appeal to the widest possible audience in a simplified and emotional manner. Yet, facts are stubborn things and not easily fitted into Party rhetoric, then or now.

All official Chinese texts claim that the majority of Tibetans were slaves and subject to punishment by torture, death or mutilation before 1950; the term feudal serfdom is used without reservation. Let’s take a moment to unpack this claim.

Indeed, before the Chinese invaded Tibet a majority of Tibetans were bound to the land and landowners. Tibetologist Heidi Fjeld describes Tibet’s social system as a ‘caste-like hierarchy’. Other prominent scholars who have researched the pre-invasion period, including Professor Robert Barnett of Colombia University, maintain that the words ‘subject’ or perhaps ‘commoner’ describe the relationship between the landowner and worker more accurately than the word ‘serf’.

This is because these individuals were in fact able to pay off their obligations and could appeal in certain cases through the Tibetan legal system in the event of a dispute. Moreover, Tibetans were more mobile and prosperous than the word serf would connote. The Chinese Communist Party links the ‘loaded’ term serf to oppression, feudalism, abuse and torture—as if this house of horrors were an irreducible truth. Tibetan scholars maintain that, in fact, the social relations governing Tibetans at the time were much more nuanced: Tibetans were not slaves or prisoners or savagely treated as Beijing’s fevered images would have the world believe.

While the poorest in Tibet led meagre lives, the situation in Tibet is comparable to other peasant societies including India, France, Russia and China during the pre-modern period in which landowners used peasants for labour. In fact, unlike the current situation, the Tibetans made excellent use of their land and animals and there was sufficient food to feed their populations, the landowners and the monasteries.

Qinghai–Tibet Railway has given millions of Chinese ‘access’ to Tibet and the ‘relocation’ of 7.5 million Chinese to the landlocked country has all but destroyed the delicate fabric of Tibetan society. Would you term this as cultural genocide? Please comment.

Beijing set out to deconstruct the Tibetan culture in three ways: firstly, Beijing has flooded Lhasa and Tibet’s other cities with Han Chinese with the objective of disrupting traditional life and religious rituals, and marginalizing the monasteries. Secondly, Beijing has instituted a ‘charm offensive’ by providing housing, public transport, and other amenities. Thirdly, the authorities have sought to ‘hollow out’ Tibetan traditions and rituals by turning the most revered sites into tourist stops—a kind of Disneyland—now visited by tens of thousands on Beijing-arranged tours.

We begin with the monasteries. From the 1970s through the present day the resistance to China’s attempts to deconstruct Tibetan culture and society has been centred in the monasteries. Under policies introduced in 1962, the monasteries had been run by monks with only indirect involvement by government officials. That policy was abandoned during the 1966–79 Cultural Revolution, when most monasteries were closed and many destroyed. Analysts visiting China in that period and in 1976 reported on the tensions between Beijing and the Tibetan people. They noted that propaganda stressing Chinese solidarity with minority nationalities was cover for problems arising out of Han efforts to control tribal cultures. Tibet was thought little more than an occupied territory, and so-called autonomous regions little better than Chinese provinces.

In the 1980’s new policies were adopted that, in effect, allowed the monasteries to again be administered by the monks. In 2011, that changed once more. Despite the guarantee of religious freedom in China’s constitution, the authorities forbid the display of the Dalai Lama’s likeness and have wired the monasteries with video cameras and microphones. In 2012, the Beijing authorities introduced a system called the ‘Complete Long-term Management Mechanism for Tibetan Buddhist Monasteries’ that places the monasteries directly under Communist Party officials who are permanently stationed in each. Moreover, every monk and nun has been assigned a government ‘companion’ for ‘guidance and education.’

Beijing’s hold is anchored by the PLA, which now has over 300,000 troops stationed in Tibet, including several mountain divisions and special operations regiments in Lhasa. The city is administered by some sixty departments and committees directly connected to their offices in Beijing. With the exception of carefully managed tourist sites, the city has been all but ‘locked down’ since the Olympic riots in 2008. Visitors report squads of PLA soldiers patrolling the streets in groups of three. Concentrations are particularly heavy around the Jokhang Temple, with military present at most intersections.

Regarding the ‘charm offensive’, beyond the presence of security forces in Lhasa, Beijing has employed ‘soft power’ in a complex process designed to improve urban areas while deconstructing Tibetan institutions. The aim is to reconstitute and modernise the cities by replacing Tibetans with Han migrants in most government offices and agencies.

The housing, communications, health, police services, commerce, licensing, and education systems are each, in effect, administered from Beijing. The education system, in particular, has been the institution of choice to socialise the next generation of Tibetans to ensure loyalty to the ‘Motherland’ and the Communist Party. Emphasis here has been given to primary school curricula and educational materials. At university level examinations are given in Mandarin, not Tibetan, and Mandarin is required for appointment to all municipal and judicial positions.

Beyond avoiding official use of the Tibetan language, a third set of initiatives is designed to extract the gravitas from Tibetan culture and traditions—in effect, to hollow out the culture. This is done by turning the temples, palaces, and monasteries—the symbols of Tibetan Buddhism—into Disney-like amusement stops accessed on tours where tickets are collected before entering. The tours are sold in Beijing for holidaymakers to ride the ‘Lhasa Express’ to Tibet, complete with drop down oxygen bags. Tickets are then presented for admission to the Potala Palace, the Jokhang Temple, and Barkhor Street—the circular prayer route around the temple where the faithful prostrate themselves (tourists are reminded this is ‘a good place to buy souvenirs’).

This hollowing out process has been accompanied by a third policy referred to above in which the PRC has poured billions of yuan into an extensive modernization program that has been people-friendly in many ways. Beijing’s ‘charm offensive,’ for which it should receive considerable credit, has delivered several new apartment blocks with hot running water, a great luxury in Tibet. Public transport has been improved (buses have heat) and access to consumer goods has been significantly expanded. Chinese claims of Tibetan progress are supported by statistics underscoring these achievements. The data also shows, however, that nearly all of the progress has been in urban areas populated by ethnic Han, rather than the countryside where 87 per cent of Tibetans live.

These improvements and frustrations combined to form complex currents, which, on 14 March 2008, erupted in a series of demonstrations and then riots in Lhasa, Gansu, and Qinghai—the same locations as in 1987 and 1989. This time Tibetans were angered by the inflation, which brought higher food and consumer prices. They were disturbed by the ‘Lhasa Express’ train from Beijing and Chengdu, which was increasing the flow of Han migrants and creating heightened competition for jobs. But most of all, they were incensed by the assault on their traditions, culture, and spiritual life.

The Panchen Lama ‘appointed’ by China (instead of the young boy chosen by the Dalai Lama) has reportedly reached out to all Buddhists. It is believed that this prompted the Dalai Lama to say in an interview that the next Dalai Lama (15th) would be born outside Tibet. It would appear that the spiritual edifice of Shangri-La is now ‘controlled’ by the Chinese. Please comment.

Not only has Beijing attempted to pervert the natural course of Tibetan Buddhist institutions and ritual that have guided the faithful for centuries, but the Panchen Lama, a Chinese puppet, is recognized only by the Chinese Communist Party. Tibetan culture and religion is strong and as discussed in this interview, we believe the Party ‘s attempts to deconstruct Tibetan culture will fail.

Indeed the Dalai Lama has stated that if there is no resolution of the succession question, it is logical that the reincarnation would occur outside of Tibet and beyond the control of the Chinese.

Chinese attempts to rewrite history will not work.

Why do you think Tibet is an ‘An Unfinished Story’?

A few months ago the National Court of Spain indicted just-retired Chinese President Hu Jintao on charges of genocide in ‘the nation of Tibet’.

The New China News Agency (the Party’s propaganda organ) proclaimed the Court had no jurisdiction in such matters, that the region is an ‘inseparable part of China’ and that its affairs are a Chinese ‘domestic concern’.

In November Tibet’s party chief, Chen Quanguo, announced a new crackdown on Internet and television access in Tibet in yet another attempt to control what people see and hear. Global media reacted to the indictment, Xinhua’s statement and the crackdown with sharp criticism of Beijing, excoriating the Party, its claims and its tactics.

Somehow, even after decades of failed policy, in which both the Party and the Tibetans have suffered punishing setbacks, Beijing continues to insist on the same sterile policies. The Communist Party leaders remain unable to define the problem they confront in Tibet and, not surprisingly, are unable to mitigate Tibet’s continued and determined resistance to their rule.

Today, as China seeks global leadership, its efforts to destroy Tibet’s culture add to troubling questions about the values informing China’s civil society. These doubts have delivered a unique form of ‘soft power’ to Tibet; the global public widely condemns China’s practices. China has paid a heavy price in credibility and world opinion. Beijing has invested a great deal over a long period of time and gained little in return.

One asks if China wouldn’t benefit from a modified policy at this point. Firstly, the Dalai Lama has agreed that Tibet is a part of China. Secondly, most Chinese know little about Tibet.

The new Chinese leadership have an opportunity to recast the Tibet issue for domestic audiences and modify the administrative structure. A suzerain relationship in which Tibet exercised greater control over its internal affairs could suit both Lhasa and Beijing. It would allow Beijing to reduce its expensive military garrison in Tibet and it would end the harsh and continuing global criticism, allowing China to actually advance its global interests. Moreover, there is a precedent for ‘One China, Two Systems’: Hong Kong. As China addresses its present challenges, which now include a troubled economy, demographic trends that will make China old before it is rich, and growing hostility among its East Asian neighbours, the leadership may wish to consider whether China can digest the Tibetan chestnut.

Tibet rests, after all, upon a coherent culture wrapped in a pervasive religion providing a clear identity—none of which the Communist Party can claim for itself.

In the end, China’s troubled Communist Party will succumb to history’s inexorable lesson that culture trumps politics—especially imperial politics imposed through force of arms.

Also read Dr Lezlee Brown Halper’s Guest Editorial in LE Volume One December 2014

Lezlee Brown Halper M.Phil (cantab.), PhD (cantab.) is a Research Associate at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. She is a Tibet scholar who has extensively travelled in and written about South Asia.

Professor Stefan Halper D.Phil (oxon.), PhD (cantab.) is Director of American Studies at the Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Cambridge. Halper is a Life Fellow of Magdalene College, Cambridge. He first visited Tibet in 1997. He has served in the White House and the US Department of State and has written extensively on US foreign policy and US-China relations.