Article in PDF (Download)

Romancing the Lavani by Aryaa Naik

The year – 1814. An elaborately decorated hall with ornate pillars and crystal chandeliers is lined up with Maratha bejeweled chieftains dressed in expensive silk , swilling alcohol in and lustily ogling a woman. They are all watching a beautiful dancer, graceful as a gazelle, her voice sweet like a mynah bird swaying suggestively to lascivious lyrics. She and her musical accomplices are the only women in the hall. This is the house of ‘ill repute’ where ‘immoral women’ perform.

Forward to the year 2014. An air-conditioned auditorium is filled to the brim with “cultured” men and women all dressed in their finery. They watch and applaud an acclaimed and respected dancer perform a Maharashtrian “folk dance”. She sways suggestively to lascivious lyrics. This is a cultural event where respected artistes perform.

‘Tamasha’ a dance form derived from various other traditional forms of entertainment is the principal folk theatre of Maharashtra. It served as a racy, titillating form of entertainment for armies of Maratha and Moughul chieftains and was also present in some form during the rule of the Peshwas. What were popularly known as Lavani Tamashas found a substantial audience in the court of Bajirao Peshwa II from 1774 to 1818. However, when the Peshwa rule came to an end with Bajirao’s surrender to the British, the Tamasha was forced to seek new sources of patronage. The lavani tamasha soon shifted to rural areas.

During this period, classical drama took the place of tamasha. While the traditional drama was perceived as moral and appropriate, the tamasha was seen as immoral and inappropriate. Respectable women did not perform in public, so the “respectable” drama had men performing women’s roles while the tamasha had women performing song and dance, resulting in the labeling of these women as licentious.

The tamasha characteristically began with a gan (a devotional offering to Lord Ganesha) and a gavlan (a comical act performed by the effeminate male artists through exaggerated feminine gestures). This was followed by the shringarik lavani (erotic song) and the mujra or collection of rewards. The lavani articulated female desire in explicit sexual terms and was almost entirely composed by males and performed by women before an almost entirely male audience, the elite among whom could bid for the sexual services of the female performers.

Change is inevitable they say and the tamasha is no exception to this rule. It has undergone several transformations since its inception in form and style, but the most significant mutation of the art form is reflected in the attempt to “purify” it.

Post-independence a sense of urgency to conserve Indian culture led to a new interest in regional cultural expression, leading to the rediscovery and reassessment of many art forms. The largely decadent tamasha went through a remarkable revival and refinement. The transformation that resulted was not only applicable to the art form itself but also to the practitioners of the art form. With attention and a certain amount of governmental support from the national and state Sangeet Natak Akademis the tamasha was altered to be more presentable to a family audience. The dance which was performed by a certain class and caste of women and was considered a part of their lineage was now being performed by women from respectable families thus putting an end to the history and lineage of a long line of performers. Though the art form has received an altered and celebrated “folk” status, the life histories of the traditional tamasha performers have remained largely invisible. A recent theatrical presentation of life histories of tamasha performers however, sheds light on implications of the transformation and the ‘resistance’ of these female artists. Did these women, essentially ignored by society find a respectable place in it after this cultural refinement? Did their lives change for the better?

Tichya Aaichi Goshta Arthat Mazya Athavanicha Pahad(Her mother’s story, indeed a mountain of my memories) , a one-person riveting play by renowned Marathi writer and theatre personality, Sushama Deshpande answers all these questions. It presents the life sketch of a tamasha dancer, Hira through a dialogue between Hira and her journalist daughter Ratna, and Hira’s reflection on her life, society and her place in it. Hira has been presented a prestigious award by the government of India her excellence in the “art form”. This has changed Ratna’s perception of her mother but, very little has as far as Hira’s place in the society is concerned.

Hira talks about her relationship with her mother who was also a tamasha dancer. Her grace, her voice, her allure. Hira looked up to her. Though her mother was a good artiste she was viewed with contempt. Hira, with quivering lips and a heavy heart recounts how she had to pay money to the court just to be able to cremate her mother as her mother’s profession did not allow her to fit within the moral boundaries of society.

Hira is not even allowed to attend her lover’s funeral; the father of her two children. He was a good man, he respected her art and loved her. Hira can’t say the same for her son, who she feels is a product of the male dominated society with a strong chauvinist ego reflected in his thinking. Her daughter however she feels is smart, determined and dashing.

Through the play Hira she reflects on her father, some of her mother’s clients and her childhood. She talks about her clients, her colleagues, how her relationship with the father of her children developed and about her love and respect for her art form.

When reflecting on the play, Sushama Deshpade shared, “I felt like writing a play on tamasha performers because when I met the women I realized how fascinating they were. They were truly empowered. They are acutely aware of the fact that they are being exploited but they make peace with the fact because they realize that they have to earn. Their relationships with their children are very complex because of the nature of their profession, there is a lack of respect from the children’s end as they don’t realize what good human beings their mothers are. The women are great on both levels; as artists and as human beings. These performers who bear the lineage of tamasha romanced with the lavani (the song), with their expressions, their graceful movements and their charisma. They subtly presented bold lyrics. Now, the tamasha is simply “performed”. It’s a pity but with the exception a few like Shakuntala Nagarkar, this institution is finished.”

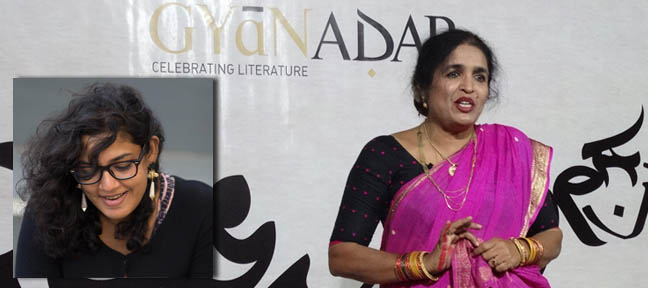

The play was recently staged at Gyaan Adab Centre in Pune, in the Indian State of Maharashtra, where Sushama Deshpande held the audience captivated for an hour and a half through her powerful performance and Hira’s insightful story. A comment on the lives of traditional tamasha dancers, the play sheds light on how attempt at “purifying” the art form has led to the professional displacement of tamasha performers with a long lineage. Though their art form had found mainstream acceptance, they still stand on the periphery of social mores.