Download PDF Here

Live Encounters Magazine April 2023

The Art World’s Best Kept Secret: The Museum of Modern Art, Zagreb

by Lincoln Jaques

Zagreb’s Museum of Contemporary Art sits in the new part of Zagreb at the intersection of Avenija Dubrovnik and Avenija Većeslava Holjevca. I say in the new part of Zagreb – the area was developed during the Socialist surge from 1945 to 1990. Between these years, in a nightmarish dream sequence from a Buñuel movie, blocks of communal towers rose steadily across the River Sava, and families rapidly moved in.

The museum itself, though, is located in the eastern block (Istok) of the grand expansion. This part of the city is home to Mamutica, one of the largest socialist housing developments in southeast Europe. The towers of the Mamutica development rise up so high it gives one the impression of being built on a hill. The whole area is a flat plain, however.

The museum sits in the midst of these decaying tower blocks like a guest who’s turned up to a metal thrash party dressed in a tuxedo. The building was designed by Igor Franić, a Professor of Architecture at the University of Zagreb, from a large pool of international submissions. Franić also designed the “Kocka mora” (roughly translated “Sea Cube”) sculpture in Dubrovnik in 2007. The artwork was a homage to fallen soldiers, “Defenders of the City”, of the 1992-1995 war.

Plonked in the middle of the ancient walled city, looking largely out of place, the oversized box of glass projected images of the lost soldiers, intermixed with reflections of the nearby Adriatic Sea, and included the poem “Hymn to Liberty” by the famous writer Ivan Gundulić. It cost 10 million HRK during a time where money was desperately needed to rebuild the city walls and replace the tiled roofs that had been relentlessly shelled by the Serbs. Not only that, it took a lot of technology to keep it going, costing half a million HRK a year. Eventually, the technology couldn’t keep up. It broke down often, so much so that the locals renamed it “Monument to Fallen [Microsoft] Windows”. It was finally removed in 2020.

To build the Museum in Zagreb, it took 6 years and 450 million HRK (US$84 million) to complete. Coincidentally, we were in Zagreb for the opening. We didn’t even intend to go if I remember. It was December, it was winter, and the snowfall was particularly high that year. But there was a bit of a fuss about its opening—there was a lot of controversy over the money and the delays and it had been in the news a lot—and on top of that my wife’s cousin was a curator for another gallery in the city centre near Josip Jelačić Square. Although she didn’t have VIP invites, she was determined to get us in.

So on an evening in December as the snow fell, we pulled on our coats and hats and boots and left our apartment in Vrbanićeva to catch the tram across the River Sava. My heart sank as we reached the museum. Word had spread of the opening, and obviously it must have been one of the few interesting things happening in the dead of winter, when Zagreb families are land-locked after the summer season spent at the coast or up in Istria.

The crowds snaked around on the expansive forecourt of the museum. Ropes had been set up and placed in rows like the opening of a Hollywood blockbuster. Half the people kept to the rules and lined up in orderly within the ropes; the other half, as it generally is in European countries, were bunching up at the grand entrance, waving their arms, or standing around in some hope that an opportunity would present itself to rush at an opening in the queue.

I told my wife to forget it and she just looked at me strangely. I remember when she first brought me to Zagreb, we were in the central city at rush-hour. Each tram that arrived in Josip Jelačić Square was packed to capacity. I simply backed off and was ready to wait for another. My wife firmly informed me that if I continued letting full trams go I would be standing in the cold for another several hours. She was doing no such thing. She pushed me through the tram doors. I think I bashed someone in the nose with my forehead. But there was no retaliation. Simply a resignation to crush one’s body into the tram and stop breathing for the duration of the journey—hoping like hell that you only needed to go a few stops until the oxygen ran out.

We got off the tram and fought our way through the crowds and reached the agreed meeting place where my wife’s cousin waited for us. She already had a plan. She’d thought it out carefully. Apparently, I was part of the plan.

The cousin had brought with her several others, all from the gallery where she worked. The hustle was that she would exert her position as a curator (the gallery where she worked was small but important in the local art scene) and she would nominate her colleagues as critics and art historians (although I think one was a cashier and the other worked in the gift shop). I didn’t know what place I had in the scheme of things. There wasn’t time to explain. Instead of lining up with the others, we headed for a side-entry hidden from the general crowd but not completely out of sight of anyone who caught on to our illegal storming of the museum. Cameras were everywhere – I think RTL Television was there and HRT Radio Television also.

I remember seeing reporters from Narodni list and Večernji list and 24sata, a major tabloid player in Zagreb. When we got to the side-door, there were bouncers pushing back a small crowd. Lots of arm-waving once again. I think one man was shaking his fist. The bouncers were holding tight, trying to tell the interlopers to go and join the crowd. Their cries fell on deaf ears.

I couldn’t help wondering what all the fuss was about. It was only art, wasn’t it? And couldn’t everyone just come back the next day when the gallery opened in its normal hours? But no, the opening of the gallery had been across all media, had infiltrated all sections of Zagreb society. To be anyone, from now on, you would have to have been at the opening of one of the most talked about and prestigious galleries in Croatia. Failing to be one of the first to enter the 450 million HRK gallery would be too much of a shame to bear. Again, I said to my wife, let’s forget it and go find a slastičarnica (patisserie). Again she gave me the same angry, disbelieving look.

We were getting in those doors.

The cousin talked to the men at the door. One shook his head. They were big men with thick necks who only wore polo shirts against the bitter cold but their constantly throbbing biceps kept the body heat in and everyone else out. Being found in the morning dead in a ditch and frozen stiff crossed my mind. This was the door, so I heard, where the celebrities and sporting icons, not to mention the world-renowned artists that had flown in from various parts of Croatia (and the world) were being shuffled through. Not that I spotted any myself.

The bodyguards weren’t buying it. Being a curator was not enough. I then discovered what my role was. The cousin said something and pointed to me. With my little snapshot of Croatian, I determined the words ‘foreigner’ ‘England’ ‘Time Magazine’ and ‘ArtReview’ (the latter 2 were spoken in English, as if to add an underlying current of authenticity). I stood mute and staring, I think at this stage my wife stabbed me in the ribs. I smiled, nodded. ‘Yes, Time!’ I said. A complete lie. The bodyguards looked at one another.

There came a moment of inner panic as I waited for them to demand my Press ID or any kind of proof to back up the claims the cousin was making. The one that seemed to be in charge stood for a moment, staring me down, then when I was about to give up and walk away (unhindered by the wrath I would have faced later from the cousin and my wife) one of them opened the glass door and we were escorted into the darkness.

We were inside one of the greatest art museums in the world.

I don’t actually remember much about the rest of that night. Everything became a blur. I think the city Mayor was there, and many artists who had pieces in the opening show; maybe even Franić himself was lurking in the shadows. A few celebrities were pointed out to me, but I didn’t recognise who they were. I remember I was introduced to many well-known artists that evening, but I can’t for the life of me remember their names or what we talked about. I have a strange habit of freezing up around people I respect and admire, artists and writers being the group I highly regard most.

There were speeches happening down on the ground floor, the many unveiling of things, but my wife and I gravitated up the levels, away from the crowds, to explore on our own. I remember looking out at the masses still lining up behind the ropes outside on the plaza, and feeling deeply guilty of the privileged way I got in. I remembered thinking how the word ‘foreigner’ had so much silly importance. I remember there were a lot of people dressed in very fine clothes.

The women wore fur coats and their hair was pinned up like 1920s film stars. I had on a possum beanie from New Zealand, sneakers that let in the water from the melting snow, a jacket that was way too warm for the heat now coming from other bodies in the crowded rooms. Normally we’d check in our coats and bags, but the check-in counter was lost in the maze of corridors and bright lights.

What I do remember most was being glad to escape the overheated museum and breathe in the cool night air again. On the tram home the moon reflected in the waters of the Sava as we crossed back over into the older district. Josip Jelačić Square was still emptying out as we changed trams to head back to Vrbanićeva. The stalls from the Christmas Markets had closed their shutters for the day. To this day I marvel how at the time I didn’t realise I’d become a part of history. It’s those little experiences that hit you out of the blue as you wake somewhere in the world at 3am and say to yourself: I was there.

It was some years later, in 2018, that I revisited the museum. This time it was October, and although the blistering heat of summer had passed, by the time we caught the tram out to Avenija Većeslava Holjevca it was gone lunchtime and hitting 30 degrees. No snow this time, just a concrete jungle of tower flats and SPAR stores and Bila supermarkets and new multi-level shopping malls. The front entrance from Većeslav Holjevac greets you like a modernist Greek temple, without all the fanfare of Gods and sacrifices. Its unassuming blandness is deceptively underwhelming. Before you crouches a geometrical pariah, daring you not to enter, unnerving you, but at the same time exotically drawing you deep into its inner sanctum to explore images and pieces that will deconstruct your thinking, like all good art galleries should do.

Inside, something I didn’t get an appreciation of years earlier at the opening night, are large, open spaces allowing you to get a sense of the magnificence of the architecture first before you intersect with the art. In fact, it was much bigger inside than what I remembered it being, which tells me just how many people were crushed into that space that night all those years ago, in contravention of any Health & Safety protocols.

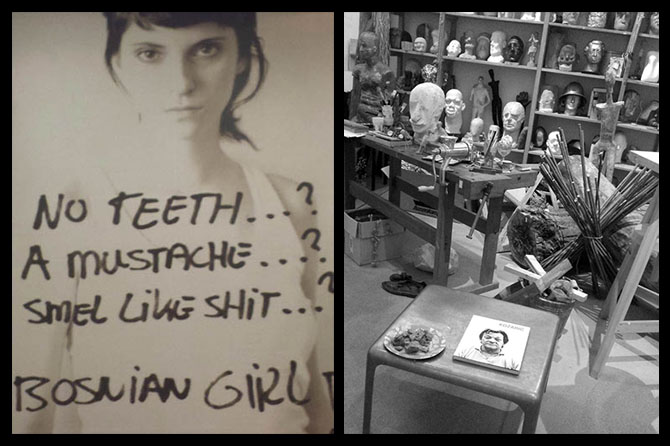

The first thing that hit me was the colossal sized art piece filling the wall as you enter the main gallery. It’s a photograph if an unsmiling girl, with a note in untidy handwriting scribbled below: ‘NO TEETH…? A MUSTACHE…? SMEL [SIC] LIKE SHIT…? BOSNIAN GIRL’

The work is by Šejla Kamerić. The graffiti was found scrawled on a wall in an army barracks in Potočari, Srebrenica, believed to be written in 1995 by a Dutch soldier who was supposed to be protecting the Srebrenica safe area. The work screams into your face and sums up everything difficult and complex about that whole conflict. Kamerić herself was born in Sarajevo. She was 16 when the war started, after her family returned from Dubai where her father worked as a sports coach. Despite the war, she attended the Sarajevo Academy of Fine Arts, specialising in Graphic Design. She belongs to a group of ‘War Generation’ artists, those who have lived through conflict and atrocities as teenagers.

Things get decidedly more interesting the deeper I venture. I walk past a room where thousands of clay heads line shelves in a type of death-mask convention, all staring out at you standing within the confines of the narrow doorway, silencing and reducing your life to small window that will close soon enough. The next exhibit that catches my attention is a series of stories written on postcards, as if these were intended to be sent out to the world as small SOSs.

The stories tell of those who have faced domestic abuse in relationships where they should have felt safe. On card 32: CROAT, MARRIED, ONE CHILD, a woman (who fittingly names her story ‘BISERKA’) tells of her escape from constant physical and mental abuse from her husband. The husband would use psychological warfare against her, saying how he would shoot himself if she left him. After each time he beat her he would say to her “Go wash your face. I want to see my masterpiece.”

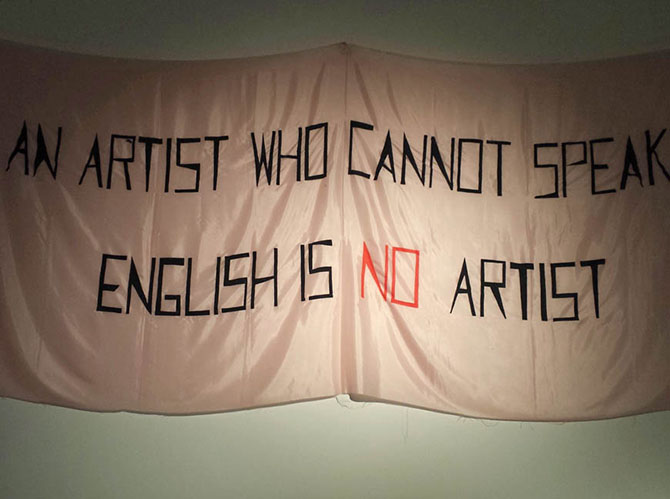

Another exhibit is a cloth with the controversial words embroidered: ‘AN ARTIST WHO CANNOT SPEAK ENGLISH IS NO ARTIST’. The ‘no’ is in red. There’s a sign advertising “Prof. Joseph Beuys, Institut [sic] for Cosmetic Surgery. Specialty: Buttock lifting”. There’s Andy Warhol style artworks and a sculpture of 2 Pinocchios tied together by a twisting rope connected the genitals with the words: ‘Mine is bigger than yours’ in letters cut from a newspaper in an echo of a serial killer’s note.

There’s a full-size yellow 1960s Renault 4 lying on its side and, in what attracts me the most, a fully recreated room from an apartment that looks to belong to a part-artist, part-writer, perhaps during the communist period.

The room is complete with wardrobe on top of which are suitcases, ready to be packed at short notice; chairs, a gas cooker, a 10-speed bicycle, a set of skis, a bed with sunken springs, a black & white TV set and a table on which are an assortment of pens, pencils, writing paper, drawing block pads, a Nordmende transistor radio and a silent gun-metal Olympia typewriter, its keys still alive and sparkling under the spotlights. The room has the feel that someone has just stepped out to buy cigarettes. But it manages to create a loneliness in the onlooker that once tapped, can never be quite released again, like a stuck key on the Olympia that will never again be able to complete a sentence.

After an afternoon of meandering through the galleries, mostly empty now and nothing compared to that opening fanfare in 2009, I feel a certain sadness. I sit for a while in the empty café that looks out across to the rush of afternoon traffic to the glittering neon lights of the Avenue Mall. The mall is full of people, walking through a structure similar to the gallery I now sit in.

But whilst the shopping mall is full to the brim, the gallery in comparison is empty, forgotten. The people’s art is Adidas, H&M, iNovine, Next, Samsung, Skechers, Tommy Hilfiger, United Colours of Benetton. Their semiotics are the signs that draw them to the labels which rule their lives, which gives them identity. But our galleries also offer us meaning in an uncertain world; they hold up mirrors to ourselves, help us understand who we are, where we’ve come from, and most importantly where we’re heading. For a moment on a cold night in December 2009 the Museum of Contemporary Art was the place to be seen.

Now the air conditioning cools only the few who come to shelter from a harsh world, to escape the sun for a while, to have those few precious moments to think deeply about our world and our place in it. Art has been telling us all we need to know since time immemorial. We just keep on ignoring it.

Here in The Museum of Contemporary Art is housed important works, a fascinating, connective narrative journey, and I hope that everyone reading this will take the time to visit if they should be in Zagreb.

© Lincoln Jaques

Lincoln Jaques’ poetry, fiction and travel essays have appeared in Aotearoa, Australia, Asia, America, the UK and Ireland. He was the winner of the Auckland Museum centenary ANZAC international poetry competition, a finalist and ‘Highly Commended’ in the 2018 Emerging Poets-Divine Muses, a Vaughan Park Residential Writer/Scholar in 2021, and was the Runner-Up in the 2022 International Writers’ Workshop Kathleen Grattan Prize for a Sequence of Poems (judged by Janet Charman). He holds a Master of Creative Writing from AUT.