Download PDF Here 13th Anniversary

Live Encounters Poetry & Writing Volume One December 2022.

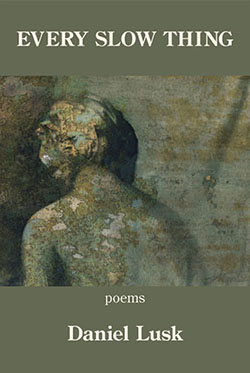

Every Slow Thing by Daniel Lusk, review by Frances Cannon.

Published by Kelsey Books (Utah) https://kelsaybooks.com/collections/all/daniel-lusk

Daniel Lusk has lived many lives and has many stories to tell, and the poems in his new collection, Every Slow Thing, offer small glimpses of these past selves, as well as reflections from the storyteller in the present moment. These pieces feel more pensive and intimate than his previous books: five poetry collections, one novel, and a memoir. This is a quiet and gentle book, with an eye on history, a sweeping hand over the author’s myriad adventures, dashes of humor, and hints of magical realism.

Daniel Lusk has lived many lives and has many stories to tell, and the poems in his new collection, Every Slow Thing, offer small glimpses of these past selves, as well as reflections from the storyteller in the present moment. These pieces feel more pensive and intimate than his previous books: five poetry collections, one novel, and a memoir. This is a quiet and gentle book, with an eye on history, a sweeping hand over the author’s myriad adventures, dashes of humor, and hints of magical realism.

These poems explore a full cast of characters in the theater of the writer’s mind: a hermit, lovers, dogs, owls, a train, a blind preacher. The speakers seem caught between faith and doubt, restraint and havoc, pleasure and struggle—we witness their progress through injury, death, love, and revelation. Their voices are dynamic, and the moods they convey include contemplative, amused, haunted, nostalgic, and appreciative. The poems explore various geographies as well, from cliffs in Ireland to farms in South Dakota. They draw on many sources, as evidenced in the diverse epigraphs: Paul Simon, Italo Calvino, Jill Lapore, Goethe, and more.

There are also a handful of ekphrastic poems, drawing inspiration from a painting by Gustave Courbet, a photograph from the National Geographic, a theater in Chicago, and a Chopin nocturne. In all, the poems show the depth and breadth of Lusk’s talents as a poet—each has its own unique shape, mood, and story, and yet they all feel connected in memory and across time. Despite the variety of characters, speakers, voices, moods, and allusions in this book, the reigning concept is the phrase contained in the titular poem, “there is beauty/ in every slow thing.” This thought manifests in many tender, detailed moments throughout the collection. The reader is welcomed into quiet glimpses of nature, domestic realms, and reveries. The book sings with vivid imagery and textures—hay, blood, rain, lace, fur.

In one of the more playful and imaginative poems in this collection, “The Oat Witch & the Old Man’s Daughter,” the reader is invited to reflect on “an old story” with the twist that the speaker lived through it to tell the tale. In this blend of myth and gritty realism, the speaker tells the story first in third person, then switches to first person to claim the story as his own. He recalls a nearly fatal accident involving a stranger from out of town who helps in the hay harvest, and who is then stabbed by “the sheaf-goat/ dressed as a child/ lifted a pitchfork to stick it/ into the wagonload/ as the tractor lept ahead.” This stranger is killed in a harvest ritual, and yet he either never dies or he is revived, nursed back to health by the daughters of the old, dead patriarch. The stranger wakes from the accident from a fever dream, without a clear sense of what happened, whether or not he died, how long he spent in the realm of the dead, or his sense of self. The poem reads like a riddle or an old trickster myth, and yet it contains little seeds of truth.

Some of the most compelling passages in this collection are lists of sensual details that surround the speaker; landscapes, flora and fauna, the names of bygone towns and lovers. In the poem “Haystacks Like Bread,” the speaker notes how haystacks gradually accumulate in a field rising “like bread dough/ into compact architecture like houses,/ stables, bars. They were my churches.” Thus, a memory of a mundane task such as stacking bales of hay transforms into reverential worship. The speaker also builds a museum of memories of these rural meadows, both unpleasant: “Snakes, mice, dung beetles, ticks,/ mites, bacteria and mold,” and pleasant “green alfalfa,/ yellowed timothy, red clover stems and flowers faded blue.” We witness the speaker howling songs over the roar of a tractor, and speaking promises and regrets to himself while he works the field. Thus each small object and chore finds its place in time, and trivialities are elevated to precious keepsakes.

In a poem titled “Ganz Andere,” a German phrase which roughly translates to “wholly other” or “quite different,” the speaker reflects on his age: 63, and his observations of the day include the full moon, brown bats, and a large green frog. He then reveals that he was “exiled at an early age/ by mystery,” and then claims that “I am the dog of uncertain parentage./ I am the dog who barks all night, / afraid of silence.” This poem reads as the speaker’s ars poetica, or an answer to the question “why poetry?” The poem itself hints at these answers: Poetry, to fill the silence. Poetry, as a balm to loneliness. Poetry, as a vocation. Poetry, as bookends to a life. Every poem in this book could offer an answer to that age-old question, if not in content, then through the rhythm and musicality of each line.

Take, for example, these lines from “Asp of Jerusalem,” which offers an unusual vision as well as a tongue-twisting phrase, “In the aspens yellow-bellied sapsuckers/ laughed themselves blue.” The music of the book fluctuates in form, line-length, and rhythm, but it’s always there, humming and bouncing from line to line.

This play and humor punctuates the collection, and one particular poem, “Nocturne No. 2 in E Flat Major,” offers a delightful surprise to the reader in the final stanza. The speaker performs a simple task: dusting an old clay pot while listening to Chopin. The shape of the pot reminds the speaker of distant galaxies, the “areola of a lover’s breast,” and an infant’s hand, yet he cannot pin a metaphor to the darkness within the pot. He offers a challenge to himself and to the reader, “we can imagine whatever we like/in that black nothingness,” and he offers an absurd vision of a “small spider/ in a brown fedora, smoking a cheroot.” The poem eventually returns to the piece of music mentioned in the title, and the speaker implores the reader to pause and listen, “notice how the music of the piano lingers/ like a slow rain on a stranger’s roof.”

This is characteristic of the nature of this book—a blend of worldly philosophy, ordinary beauty, and magic.

This collection offers a tour of memories, a cabinet of wonders, several folk-tales, allusions to other texts and works of art, love letters to figures from the past and present, and observations of the natural world. The music of “cricket, frog, and goose” accompanies the poems, along with a rotation of visions both real and imagined. This book feels complete, satisfying, and fresh, like a whole loaf of sourdough bread from a wood-fired oven. This is Lusk’s offering, like a communion; crack open the crust and share in the warmth of a long life, well-lived.

© Frances Cannon

Frances Cannon is the Managing Director of Sundog Poetry, as well as a writer, artist, and instructor. She has previously taught at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, Champlain College, the Vermont Commons School, and the University of Iowa.

She has an MFA in creative writing from Iowa and a BA in poetry and printmaking from the University of Vermont. Her published books include: Walter Benjamin: Reimagined, MIT Press, The Highs and Lows of Shapeshift Ma and Big-Little Frank, Gold Wake Press, Tropicalia, Vagabond Press, Predator/Play, Ethel Press, Uranian Fruit, Honeybee Press, Sagittaria, Bottlecap Press, and Image Burn, a self-published art book.

She has worked for The Iowa Review, McSweeney’s Quarterly, The Believer, and The Lucky Peach. Her writing has been published in The New York Times, Poetry Northwest, The Iowa Review, The Green Mountain Review, Vice, Lithub, The Moscow Times, The Examined Life Journal, Gastronomica, Electric Lit, Edible magazine, Mount Island, Fourth Genre, and Vol. 1 Brooklyn. Website: https://frankyfrancescannon.com

Instagram: @frankyfrancescannon Twitter: @francesartist