Download PDF Here Live Encounters Poetry & Writing Volume One Sept-October 2022.

Gardening with Mark, a short story by Fred Everett Maus.

When I was younger, I tried to kill myself—once when I was sixteen, again when I was nineteen, with pills both times, the first time with my mother’s sleeping pills, the second time with my own clonazepam, which I was instructed to use, only rarely, for my anxiety or insomnia. After the first time, I talked with our family doctor and persuaded him that it was an accident. That was the assessment I wanted him to give my parents. I knew they couldn’t afford psychotherapy, and I didn’t think therapy would help anyway. The second time, my college counseling center connected me with an excellent therapist, Marilyn, and a wonderful psychiatrist, Kate, who still helps me with medication. They took away the clonazepam and put me on Wellbutrin and Lexapro, the first in a long series of fairly successful attempts to match my illness with the right meds.

Recently my relationship with Mark had felt serious, perhaps lifelong serious, and I thought it would enrich our connection if we started to talk about that difficult part of me. We had a pleasant Chinese dinner together, and then went to my apartment to sip some wine. We talked a bit, redundantly, about how good dinner had been.

I paused, and then: “We’ve been seeing each other four months now.”

“I know, Paul. Four wonderful months.” The sky outside was dark, as dark as it gets here in the city. There was a quiet hum from the traffic, three stories below. If I were closer to the window, I could have watched the traffic lights changing, and changing again. It was strange how those rhythms could be comforting.

“I’m sorry, I am not ready. I need a place of my own. I can’t live with someone just now.”

“That’s not what I meant, Mark,” I said. “I wasn’t bringing that up again. We are fine this way.”

“Tonight, for instance. I need to leave soon. I have to get up early for work.”

“I get it. Thanks for spending time with me on a Tuesday.”

“Of course.” He smiled, tired and a little distracted.

“It’s been four months,” I said. Now he looked straight at me. Mark had a characteristic direct gaze, but this was different–alert, curious, maybe apprehensive.

“Yes. It has.”

“It’s … it’s that I want to tell you something.”

“Well. It’s late now. I’m sure it can wait.” I heard it first, and then out the window I could see a jet, approaching the airport, lights blinking.

“It has already waited.” I regretted the words and my firm voice, but now I had to continue. “You know that I talk with a therapist.”

“Yes, of course. I’ve done that too. It’s not a big deal.”

“Sometimes it is. I have a diagnosis.” I am not sure why I paused.

“Oh, everyone does. I have been diagnosed three times with adjustment disorder so that I could access my insurance.”

“Actually, she’s not a therapist. She’s a psychiatrist. Mark, I have depression.” The refrigerator hummed loudly, with that odd sound it made from time to time, not, it seemed, the sound of a motor, but something else.

“I’m sorry that you are depressed,” he said after a moment, and I thought that I had never heard him sound so insincere. Then he was himself. “Paul, I know you very well, and I don’t think of you like that. We all get sad sometimes. If there is anything wrong with you, it’s that you work too much. You don’t know where to draw the line. I’m sure it affects everything in your life. You probably made yourself really tired at some point.”

“Mark, it’s not that I am tired. I have depression. It’s a medical condition. Sometimes I feel like I can’t do anything, even get out of bed. Sometimes I feel like there is no value in anything, in me or anything in life. I try to remember that it is just something my body does to me. I’m better now, thanks to my meds, but Mark, in the past it was often very hard.”

“Paul, you never told me.” The refrigerator stopped humming and the apartment was harrowingly quiet. The car sounds started up again, another change of the traffic signals.

“It has been months, and you didn’t tell me. We’ve been together four months, and now you are telling me that you are sad. What have I done wrong? What can I do for you? Is it about moving in with you?”

“Mark, it has nothing to do with you. It’s a medical condition.”

“You didn’t tell me. You don’t trust me.”

“Mark, I am telling you. This is not easy for me. Basically, I don’t tell anyone unless I have to. I am telling you because I trust you.” I wondered, for the first time, whether I actually did trust him. What was happening to us right now?

“Is it because I don’t want to move in with you? Speaking of my apartment, as you know I work tomorrow. I need to go home. And sleep. I hope I can sleep after this conversation.”

I had nothing to say. I watched him put on his coat and let himself out.

It was the closest we had come to a quarrel. Mark was even-tempered and kind. I had never seen him angry, and in this conversation, I sensed only hurt. The next day, I went over the conversation again and again, wondering where I was at fault. I never wanted to hurt Mark. I cherished his quiet happiness, and I depended on it to ground my own unsteady feelings.

Suddenly, though, mid-afternoon, I realized: Mark was saying he didn’t want to know me; or didn’t want to know certain things about me. What was this unfamiliar boundary that I had encountered? I was at the bookstore. Mid-afternoon was often a nice time of day there—not many customers, just me and my boss in a quiet place, good for reading or thinking. Or sometimes writing, but I was shy about working on my poems when my boss was around. I knew that he was sure of himself as a judge of literature. I could imagine him insisting on reading a poem-in-progress, and then letting me know that the poem was poor. Michael was a somber man in his fifties, single, with a persistent air of disappointment that readily transformed into harsh criticism of those around him. I was sure he had grown up with ambitions grander than his twenty-five-year run as owner of an independent bookstore. Though it never came up between us, I felt he was 100% heterosexual. For one thing, most people think I’m cute, and I sensed no sexual response from him. I was also pretty sure that he was sexually inactive. Nothing about him intimated any kind of bodily satisfaction. I didn’t like him, but I liked the job he gave me, so I took care over our interactions.

Mark and I first met at the gym. That might sound sexy, and I guess for us it was, sexy by our shy-nerd standards. I had seen Mark at the gym before. I thought he was handsome; some people might not. Maybe he was kind of ordinary looking. He was not tall, 5’5”, which matched my 5’7” pretty well. We were both skinny, with barely visible muscles. My dark brown hair was about as boring as his sandy hair, both of us with convenient short cuts. We didn’t exercise to be buff but, I suppose, to stave off illness and death. I thought I had seen him looking at me before. On the day we met, he came over to talk as I was doing some triceps work. “May I give you advice?”—the first time I heard his soft, unemphatic voice, neither high nor low, neither butch nor feminine. That safe vocal neutrality that some of us were lucky to have.

“Sure.”

“You only need to move your forearms. From the shoulder to the elbow, you need to be like a rock, immobile.” He was right. I was pushing down with my whole arm, moving from the shoulder, with loose elbows.

“Like this?”

“Yes, much better!” Later we chatted a little more. And later, we happened to be leaving at the same time, so I asked if he wanted to get coffee.

Neither of us was obviously gay. I don’t mean I’m proud of that, but it often made things easier. Not that either of us was obviously straight, either. We both fit into the “nerdy asexual” category, and it probably saved our lives in high school. Now, in our thirties, it mattered less to our safety, but it was still who we were. Nonetheless, for whatever reason, from our first words to each other, neither of us doubted that the other was gay. We immediately felt safe with each other, and mutually attracted. Were nerdy asexuals supposed to pair off? Weren’t we supposed to be looking for a little more contrast? Anyway, we did what we did. By asexual, I mean that’s how people thought of us. But anyone who saw my bedroom trash basket when I was in high school would have known that solo sex was happening a lot. Same for Mark. We had both been single for about a year when we met; lots more tissues.

On that first date, if that is the word, Mark and I had the unexpected ease that sometimes happens between people, as though we had known each other for much longer than two hours. We exchanged phone numbers and two days later we had coffee again. The second time, we talked about our families and other people we knew, about some successes and disappointment in our lives, feeling more and more attuned, and ended up a few blocks away in Mark’s bed. Over the next weeks we flourished in each other’s company. Soon we had keys to each other’s apartments, and we saw each other three or four times a week, sometimes with sex, sometimes not, sometimes sleeping over, sometimes ending up in our own apartments, three blocks apart.

Neither of us had had an exciting life. That was one of the ways that we matched. Mark had gone to a community college, and after graduation he got a job in a camera shop, selling goods at first, then, as his skills became known, advising customers and doing repairs. He had had the job twelve years. He was known, now, for his reliability and honesty, and everyone said he was a magician at repairing old cameras.

I had gone to a pretty good state university in the city where I still lived, majoring in English, and then I realized that I had no ideas about what to do next. I waited tables in good restaurants for—it’s hard to believe—four years. I was sort of charming, and I had a natural impulse to please people and keep them comfortable; the restaurants exploited these qualities to the point of exhaustion, sometimes even revulsion. And three times I lost waiting jobs when I was feeling down and couldn’t leave my bedroom for several days. Finding the bookstore job was a lifesaver, even if, at the beginning, I sometimes went to the bathroom to cry after a dressing-down from Michael. My first bad experience with him came about a week into the job. I was lost in thought, and then I realized he was standing two feet away, glaring at me. “Are these shelves alphabetized?” he said, pointing to Fiction R-Z, not overtly angry but more intense than I might have thought the topic required. Obviously, he knew the answer to the question, and I did not, and he knew that I did not.

“I’m sorry,” I said immediately. I felt submission flood my body. I wondered if I looked like a sad scolded puppy.

“Customers will not buy the books that they cannot find.” He didn’t raise his voice, but there was something startling in the sound, something poisonous.

“I’m sorry,” I repeated.

He wasn’t finished. “Paul, I can’t tell whether you are selectively blind or just very stupid.” The venom was gone now; he had returned to his usual preen when he felt comfortably superior. I would learn to expect interactions like this one, arriving out of nowhere every few days.

But twice in my first two years, I missed more than a week of work, lying in my bed, barely able to get up and feed myself, and Michael acted as though it was just something that happens and welcomed me back. I guess he was not all bad, though that was hard to remember when he was a shit, which he so often was.

Sex with Mark was different from anything I had ever experienced. Mark preferred to top, so that’s what we mostly did. (I liked either role, a lot.) He also strongly preferred face-to-face. Fucking went very slowly with Mark. He would enter carefully, taking a long time, often murmuring, almost as though to himself, “I don’t want to hurt you.” Then he would start to—I could say thrust, but that sounds too forceful. He moved in and out, slowly, steadily, for a long time. When he was going to come, he flushed, breathed more deeply, looked into my eyes, and radiated a special intensity; nothing sped up much. Finally, he would exhale, making a quiet sound of contentment, “mmm,” and a slow smile would find his face, and he was still, his eyes closed. I suppose he just didn’t have that jackhammer gene; or maybe he backed away from anything that felt scary or out of control. As he fucked, he would close his eyes for a time, deep inside himself, and then open his eyes, looking intently into my face. This alternation, eyes closed, eyes open, was a rhythm, like impossibly slow breathing. Especially when he looked at me, I sensed that for him the experience was even more about my pleasure than his own. It made me emotional, being cared for by his cock in that way; sometimes I got tearful.

If I asked to top, he always said yes. Getting fucked, he would go into a kind of quiet trance, blissful. Once, early on, I got excited and started to pound him, the way I had always done with other men. He suddenly took my head between his hands, looking into my eyes from three inches away, and whispered, “It’s all right. It’s all right, Paul.” For a moment, we were still. Then I continued, slowly, in the style I had learned from him.

I admit I missed the more vigorous fucking, my own and that of my previous tops. There was a way I often cheated on him. Alone in my apartment, I jerked off to porn that had the rough energy that I would never get from him. It was easy to find; I went to porn sites and used the search terms “hard gay fuck.” The habit was a little risky, with him having the key to my apartment. I didn’t want him to walk in on me, but I knew his work schedule. Though I felt kind of bad about it, I thought it stabilized our relationship

As we started to see each other often, I found some significant differences between us. We liked to watch movies together, but we didn’t like the same movies. He really didn’t want to see movies about gay men. Somehow that was triggering for him; I didn’t understand why. Neither of us was political—we were “relieved to be under the radar” gays—but sometimes I wanted to watch stories about people like us. In general, he was unlikely to accept my suggestions about movies to watch together. We saw much more of Desperate Housewives than I would ever have watched on my own. When he proposed viewing White Chicks again—it would have been the third time—I said no, never again.

We also had different relations to photography. I had a brief, enjoyable period in my mid-twenties when I tried to make artistic photos. I wasn’t bad and I wasn’t really good either. Mark had been fascinated by cameras since he was in middle school, but he didn’t care about taking photos himself, and he had no interest in the work of famous photographers. I had a few photography books in my apartment, some gay or gayish stuff like Peter Hujar and Ryan McGinley, some others, Helen Levitt, Walker Evans, some that I had had for a long time, others that I had found in the bookstore. From time to time, I enjoyed sitting with a book of photographs for an hour in the evening. The books did not interest Mark. I never tried to show Mark my poems; I knew what would happen, and I didn’t need to experience his indifference. I think my inner art fag was disappointed in me for pursuing this relationship, but I cared more about Mark than about the art fag.

The one kind of art that interested Mark was classical music. He studied piano from childhood until he was in tenth grade. He had an old upright piano in his apartment, and he played every day. It had a small sound compared to more professional instruments, but it was beautiful to hear. A piano technician visited when needed: Mark kept the instrument in excellent condition and perfectly in tune. Mark had no interest in listening to recordings of classical music. He just liked to play. I asked him why he stopped studying. “There was no money, and it’s not like I wanted to become a pianist.” But his playing sounded advanced to me. He particularly loved Schubert’s music, delicate sweet pieces. I asked him if he knew that Schubert was gay. He didn’t know and didn’t seem curious to hear more. Sometimes I sat next to Mark as he played, watching his hands and face. More often, I would lie on the sofa, close my eyes, and go into a kind of dream.

From hearing Mark play, I soon had a favorite piece by Schubert. It was the first movement of a Sonata in G major; Mark told me it was sometimes called Fantasy. I liked the name Fantasy, an invitation to let my imagination roam.

The music started with a long gentle hug, Mark caressing the middle of the keyboard. Suddenly, though, Mark’s left hand plunged very low: there was thunder, far away, and then a moment later, in the distance, sunlight through the clouds. Tender hugs again, holding a little tighter this time, and then an unexpected delicate dance. The dance flew higher and higher; the left hand stood on the ground, looking up. Then the dance transformed into a rapid, sweet flicker.

There was a middle section. Those loving hugs became something harder, more serious, almost frightening. Had the thunder I heard before become a storm? Mysteriously, the new harsher music alternated with that lovely dance. But before long, the troubled music led back to the opening. Loving hugs again, sweet dancing, and the thunder was gone. That return to the opening music brought me an exquisite sense of safety and trust. Always, what I saw and heard when Mark played piano fused with my knowledge of how those same hands could touch my flesh, and most of all when he played this Fantasy.

I found performances of the piece online, but they affected me much less. For me, the music was the beautiful sound of Mark’s nearby body. I also discovered that professional pianists played the middle section much more brutally, and their versions were unsettling. I wanted Mark.

As I said, Mark and I had an awkward, incomplete conversation about my depression. The next day, Wednesday, was not a day when we would normally see each other, but I didn’t want to leave that conversation hovering between us. After work I went to his apartment. It was about 9:00 PM; my lovely boss had asked me to work several extra hours, with no notice. Outside Mark’s door, I paused. Something was happening: crashing piano chords, wild and fierce, in a maddening repetitious rhythm. It sounded like Mark was trying to beat the piano to rubble. It was the ugliest piano sound I ever heard, and it went on and on. I thought there were a lot of wrong notes, too, nonsensical clumps of sound, though I didn’t really know about such things. From what I heard, I was sure that Mark’s face had some terrifying expression that I had never seen. An unworthy thought appeared in my mind: “He certainly doesn’t pound me like that!” I tried to set it aside. I didn’t want to know more, and I left, queasy and shaken. As I walked down the hall, the piano sounds faded. I entered the stairwell, and I couldn’t tell whether I was still hearing the piano or only its resonance in my head. I was worried for Mark and frightened by him, and disconcertingly aroused by this unknown animal version of my boyfriend.

When I got to my apartment, I went to YouTube immediately to learn whether I had heard an existing piece of music or some astonishing invention of Mark’s. It made sense to look for piano music by Schubert. After a while I found it—Moment musical No. 5 in F minor. It was the same music, but less disturbing in the online recordings than what I had heard earlier. I listened to it again and again with different pianists. Some interpretations sounded downright tame. I found performances with some of Mark’s wildness by Grigory Sokolov and Vladimir Feltsman. I was right that Mark had played a lot of wrong notes. Also, the actual piece had loud parts and soft parts; Mark’s playing had only been loud. And it was a short piece; Mark was playing it over and over. I couldn’t stop listening to the online recordings. About an hour of nausea and jitters.

I really needed to see Mark the next day. I fell asleep slowly, fragments of F minor Schubert floating around me, sometimes scratching against my skin, but then I slept soundly.

Thursday, a good day at the bookstore. Many customers knew that if they described a book to me, I could probably identify it and find it for them. Putting my degree in English to work! There were a lot of those queries around lunch time that day, but mid-afternoon brought a long period of quiet. Over the last few days, I had been working on a poem, near completion. I started to think about it again and for once, I ignored my fear of Michael. I sat at the main desk with my laptop and, lo and behold, finished the poem in about an hour. No harassment from customers or boss.

I didn’t write poetry in college. I started a couple of years after graduation. I never had teachers, though I read some poetry in college, and much more once I started writing. I discovered that writing offset the harrowing feeling that my waiter job was my essential reality. Before long, I published a few poems, not in leading journals, of course, but in good ones.

This new poem took the form of a dialog:

Thin Line

I spoke: The full moon nourished us.

It overflowed. Soft as milk,

silver splashed down, delicious, and

we looked around, bewildered.

But tonight, a simple

curl, to trace

a shallow bowl

or two hands, cupped.

And we have nothing to offer

but the time our light will take,

whether we give it or not,

to grow round again.

You replied:

The heavy eyelid

almost hides the glow of an ample soul.

No one sees, through a gap

so nearly closed.

No move I make will

catch that eye. In my gratitude,

under this sky,

in my envy, I feel alone.

Was it any good? I could never tell. Two people looking at the same thin curl of a moon, thinking different things. Was it foolish to write a poem about the moon when so many already existed? I thought of the characters as lovers. Part of the idea of the poem was that the first character tried to speak for both—typical masculine entitlement, though I didn’t gender the characters. And the second character responded by describing isolation. As always with my poetry, it was not about me but created an imaginary situation. I seldom knew where my ideas came from.

Finishing “Thin Line” restored my balance and calm. I sent a message to Mark to arrange dinner.

I had the idea of going to the same Chinese restaurant as Tuesday’s dinner. Would that help us pick up the thread, maybe return us to where we were before that failed conversation about my depression? I wondered whether we would talk about Mark’s explosive bout with the piano. I arrived first. I felt alone. The glow from finishing my poem was gone, and I was nervous. I looked around, at the worn white tablecloth, the old menu that I could probably reproduce from memory, the shiny red walls and cheap looking red fabric decorations, the many empty tables, a middle-aged heterosexual Asian couple eating together on the other side of the ample room, the swinging door to the kitchen with its tiny round window, the stained brown carpet, the dingy white acoustical tiles, the one window with its Venetian blinds nearly closed. The wife of the owner entered from the kitchen, ancient, her hair beautifully, unnaturally black. She looked at me and disappeared without saying anything. The front door opened for three teen girls, two of them Asian or Asian American, the third pale and blond. Street sounds for a moment, cars passing, a distant conversation, then the door closed and there was a hush. The three girls and the couple all began talking at once, but quietly, as though respecting the stillness of the room. I couldn’t understand what they were saying, the girls with their soft English, the couple with their Asian language, but I listened to the music of their voices, the pitches and wavering melodies, the overlapping phrases, the changes of sound-color as different individuals spoke, the intermittent silences. The sounds relaxed me. As I listened, I noticed for the first time that there was a faint clatter of pots, plates, and utensils from the kitchen, and sometimes voices muted by the door.

Then Mark was sitting down, looking at me as he always did after time apart, with warmth, gratitude, a gentle smile, his direct gaze. “Paul,” he said. “You know that I love you.”

“Yes, of course.”

“I wanted to say that. I don’t always say it. I love you.”

I waited, meeting his gaze, starting to feel the calm that he so often brought me. “I was thinking about what you are to me,” he continued. “I think I can say it right. You are my peace. The world is not simple. With you I feel the world can be quiet, and still, and good, and peaceful.” I was overwhelmed by the beauty of this man and the beauty of what he was saying. I felt we were back together, like before, our recent days of confusion erased.

“I don’t need to know everything about you,” he said. “There’s the part of our lives that we have together. We need to take care of it. It’s a garden, our place of love and safety. Please help me cherish that garden.” Caught up in this vision, I melted. How could I have deserved to find this wonderful man?

Then we ate and talked and laughed, finding joy in each other. A bit later, we were serious again. “Mark, how do you see the future of this relationship?”

“Well, I’ve thought about it a lot. I think we’ll continue just as we are for a while, and then at some later time we will get married. I can’t imagine anything else.”

We had never mentioned marriage before, but what he said felt good. We ended up in my apartment; a tender, slow fuck, and Mark slept over.

Mark left early in the morning. Friday was my day off from the bookstore. I woke up aglow with love. But as the morning passed, my good mood began to falter. Mark seemed to know what he wanted, and it was what I wanted, too, wasn’t it? Or mostly it was what I wanted, and the other parts didn’t matter. Or they did matter, but nothing was ever perfect, and nothing else was as good as what Mark and I had found.

Then I flinched with the sudden return of the recognition: he didn’t want to know all of me. He wanted to create something by building it together and by excluding what he didn’t like. But wasn’t that what people always did? I didn’t know.

I had felt so clear and confident, last night and earlier today, and now I couldn’t think. I was glad I had a therapy appointment that afternoon. I needed to talk about Mark with someone who wasn’t Mark.

Then I was with Amy in her office, a tidy room that was a museum of beige. No sounds from outside the room bothered us. With therapists, my history was spotty. I would try one for a while, maybe six weeks, then I would start to feel that it wasn’t going anywhere, and I would take a long break, sometimes years, before starting again with someone else. It was different with my therapist Marilyn, who along with Kate had saved my life when I was in college. It wasn’t just the diagnosis of depression. I had been living away from home for the first time and I didn’t know who I was, sexually or in most other ways. Marilyn told me it was all right to be gay, and she said it so many times that I finally believed her.

This was only my third meeting with Amy. We were getting to know each other. I tried to explain what it is like to be with Mark. “He’s not very interesting. Maybe he’s the least interesting person I know.” She raised one eyebrow and stared silently. “I mean, it’s a lot like being in love with a Labrador retriever. He’s usually so sweet. Not always, but … It’s not exciting to be with him, but it’s as pleasant as possible. When I’m with him, it’s like I’m on my second martini.” The eyebrow went up a little more. “Sometimes it makes me think I’m not interesting either, and … maybe that’s OK.” As I was speaking, I realized I was leaving out the scary part about the Schubert Moment musical. But how to describe that inexplicable deviation from everything I knew about Mark? Actually, I was leaving out a lot. What about that conversation about the garden?

A pause, and Amy said, kindly but with an edge of purpose, “What does it mean, for you, to have a boyfriend?”

I was pleased; she understood me. “Yes, exactly,” I replied. “What does it mean to have a boyfriend.” Then I changed the subject to some other stuff from the preceding days. My boss, that prick. A few hours after the session, walking through the city by myself on a pleasant evening, I realized she might have been asking me a question, and maybe I was supposed to try to answer it. I noticed a CVS across the street and remembered that I needed to pick up a few things. Toothpaste, definitely, and I was low on rubbing alcohol. And it never hurt to look for good discounts on anything else that I might use.

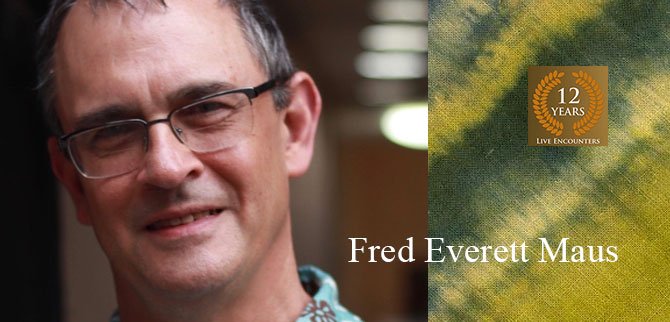

© Fred Everett Maus

Fred Everett Maus is a musician, writer, and teacher. He teaches music classes on a range of topics, for example a recent course on “Music in Relation to Sexuality and Disability” and a recurring contemplative course “Deep Listening.” He is a trained teacher of mindfulness meditation and Deep Listening, and a student of music therapy and object relations psychoanalysis. He has published prose memoir and poetry, for instance in Citron Review, Palette Poetry, Roanoke Review, and Vox Populi, and in Live Encounters Poetry and Writing March 2022. He lives in a house in the woods north of Charlottesville, Virginia, and in Roma Norte, Mexico City. The Oxford Handbook of Music and Queerness, which he co-edited with the late Sheila Whiteley, has just been published.