A brief overview of The Cinema of Bimal Roy by author Dr Shoma A Chatterji. The book is published by SAGE Publications.

Bimal Roy won two Filmfare hat-tricks as best director (in two spells of 3 consecutive years each), and one best picture award (a total of 8 Filmfare awards). When Bimal Roy went on stage to accept his Filmfare trophies for Do Bigha Zameen in dhoti, kurta and chappals, Bombay’s upscale film coterie raised a hue and cry. Bimal Da was only underlining his signature: simplicity and minimalism. Do Bigha Zameen won a special mention at the Cannes and Karlovy Vary film festivals (1955-56). At least 12 of his films – Udayer Pathey, Humrahi, Do Bigha Zamin, Biraj Bahu, Parineeta, Devdas, Madhumati, Usne Kaha Tha, Kabuliwalla, Sujata, Parakh and Bandini represent one of the most brilliant epochs of Indian cinema. No account of the evolution of Indian cinema can be complete without an assessment of these films. They represent the pilgrimage of a true and dedicated artist. In them can be seen the maturing from poetry to philosophy, from emotion to music.

From Udayer Pathey (1936) to Benazeer (1965), the Bimal Roy era in Indian cinema spans three decades of dedicated filmmaking. Before wielding the megaphone, Bimal Roy was cinematographer for P.V. Rao’s Nalla Thangal (Tamil), Barua’s Devdas, (Bengali, Hindi and Tamil, Manzil, Mukti and Bari Didi. He was a strong and silent human being with speech conspicuous by its absence. He was almost coerced into all sorts of associations and committees, even as he kept himself distanced from the political wrangling that formed an inevitable part of all these actions. He won awards –left, right and centre, but after some time, they did not seem to matter to him one way or another. Members of his technical crew and his acting cast won awards too, and during his time, were considered to be among the best in the industry.

From Udayer Pathey to Bandini, there are innumerable instances of screen performances and technical achievements never known to have been attained earlier. Though his background is traced back to the days when screen acting was directly influenced by the melodramatic exaggeration that marked theatrical performances, Bimal Roy was noted for his marked restraint. He evolved a subtle, normal mode, contributing to the richness of the tapestry of the realistic theme of his films. The visual brilliance of the filmmaker, apparent in his pre-directorial works like Chambe Di Kali in Punjabi and Nalla Thangal in Tamil, was mature, confident and certain. He is said to have had an almost uncanny sixth sense about the positioning of the camera. Even when an independent cameraman worked for him, he would come to the set, look through the lens, and ask for the camera to be shifted at least nine or ten times. Kamal Bose and Dilip Dutta were his regular cinematographers.

Lighting, an important element in his works, acquired greater vibrancy in Parakh, Sujata and Bandini. Whenever the narration grew nostalgic or throbbed with inner crisis, whether in anguish or in ecstasy, the mood was captured in delicate chiaroscuro patterns of black, grey and dove white. The camera was his brush and his unfailing grip over it made him manoeuvre it with gentle strokes, sweeping into his canvas the rich poetry and the powers of human beauty, the intensity and the variety of human emotions.

His narrative was unhurried, lingering, yet never tended to drag like slow-paced films usually do. The editing was marked by his characteristic spontaneity while his dialogues were always delivered in low-key and soft tones. Loudness, in other words, was conspicuous by its absence. Pran, who played villain in Biraj Bahu and Madhumati, made more eloquent use of body language and facial expression than voice for both films. Bimal Roy perhaps, is the only filmmaker of the post-Barua-Debaki Bose era who towered over the Indian cinema scenario with such consistent command over the medium. His work is a fine blend of the sophistication of P.C. Barua, the emotional lyricism of Debaki Bose and the skilled craftsmanship of Nitin Bose.

Bimal Roy’s first directorial assignment under the NT banner was a 1000-feet government sponsored documentary on the Bengal famine of 1943. When he went on location to shoot the film, the masses turned their anger towards him, not allowing him to shoot. But he managed to win them over and got some good footage for the film. B.N. Sircar himself chose Udayer Pathey, an unpublished story by Jyotirmoy Roy, for Roy’s debut feature film. The film turned out to be a big commercial hit and the story came out in book form afterwards. It ran continuously for one full year at Calcutta’s Chitra Cinema. The story later turned into a play and the entire dialogue was transferred onto eight discs that sold very well, creating a new way of marketing dialogue. Udayer Pathey introduced a new era of post-WW2 romantic-realist melodrama that was to pioneer the integration of the Bengal School style with that of Vittorio De Sica.

Udayer Pathey soon had a Hindi version called Humrahi, completely re-shot on new sets with the same artistes. However, Humrahi did not repeat the success of the Bengali original. His leanings towards the poor and the downtrodden perhaps came from his basic humanism rather than from purely Leftist leanings as some critics opined. His leftist leanings of any, stemmed from conviction and not from active association because he never held any party ticket. Some of his political ideology is reflected in the way Udayer Pathey’s hero Anoop’s room. His walls were filled with portraits of national leaders and great thinkers as different as Karl Marx and Tagore. A few Tagore songs in the film became big hits. There was a fiery zeal in his earlier films, which was replaced with a mellow social concern in his later films. One of his most notable qualities was the total restraint he practiced in keeping away from any kind of political propaganda or pamphleteering in any of his films.

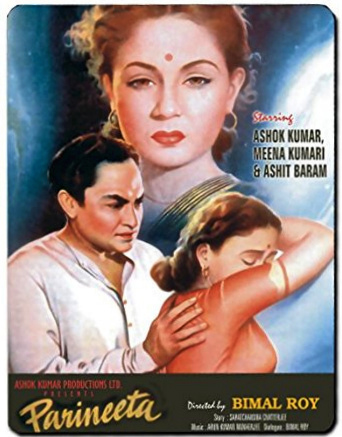

His next film in Calcutta for New Theatres was Anjangarh in Bengali and Hindi based on Fossil, a short story by Subodh Ghosh. This was followed by Pehla Admi in Hindi and Mantra Mughda in Bengali, based on a noted literary piece of work by Bonophool, neither of which could live up to the expectations raised in his first directorial film, Udayer Pathey. He also wrote Manoj Bhattacharya’s Tathapi in 1950. In the same year, he migrated to Bombay. He was invited by Bombay Talkies to make Maa, and had come to Bombay initially only for six months. He began to receive other offers such as Parineeta, based on a sweet love story by Sarat Chandra and produced by Ashok Kumar with beautiful music that in time turned into a signature for every Bimal Roy film. “I consider Parineeta to be the most beautiful and dignified celluloid metamorphosis of an original Sarat Chandra classic that has no parallel in cinema till this day,” says journalist Shankarlal Bhattacharya. When he firmly established himself in Bombay, Roy decided to found his own production banner, under the name and style of Bimal Roy Productions, using as his emblem, the Rajabai Tower of Bombay University, far distanced from the more obvious and visually opulent emblems used by Raj Kapoor, Mehboob, New Theatres or Prabhat.

Do Bigha Zamin was the turning point. The film continues to remain the most significant film that bears the distinct stamp of the Italian neo-realism school from Bimal Roy’s films. Do Bigha Zamin (Two Acres of Land) was released in 1953. It is a realist drama based on a story by Salil Choudhury who loosely adapted this from a Tagore long poem of the same name. The story is about a small landowner Sambhu (Balraj Sahni) which opens with a song celebrating the rains that put an end to two seasons of draught. The song goes – hariyala saawan dhol bajata aaya. Sambhu and his son Kanhaiya (Ratan Kumar) have to go and work in Calcutta to repay their debt to the merciless local zamindar (Sapru) in order to retain their land. In Calcutta, Sambhu becomes a rickshaw-puller, facing numerous hardships that lead to his near-fatal accident, the death of his wife (Nirupa Roy) and the loss of his land to speculators who build a factory on it.

Though promoted as the Indian epitome of Italian neo-realism on celluloid, in retrospect, there is more of the melodrama than neo-realism in the film. The script and the humanist acting styles, including a hard but kind landlady in the Calcutta slum and the happy-go-lucky shoeshine boy (Jagdeep) who takes Kanhaiya under his wing while humming Raj Kapoor’s awara hoon number all find their ancestry in Nitin Bose’s ruralist socials at New Theatres such as Desher Maati in 1938, enhanced by IPTA overtones in Salil Choudhury’s music. The film’s neo-realist reputation is almost solely based on Balraj Sahni’s extra-ordinary performance in his best-known film role. Also remarkable is Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s editing, virtually eliminating dissolves in favour of unusually hard cuts from the falling wheel of the film’s famous rickshaw race sequence to Kanhaiya coming to the bedside of his injured father. Mukherjee claims that such a cut from day to night was unprecedented in Indian cinema. Sahni however, is reported to have given a similar performance along neo-realist lines in K.A. Abbas’s first film Dharti Ke Lal (1946).

He held back the release of the completed Parineeta in favour of Do Bigha Zamin, which is said to have offended producer Ashok Kumar at the time. He set up his own sound stage and an unpretentious office at Mohan Studios in Bombay’s Andheri and went on to direct Baap Beti, Naukri and Biraj Bahu under his own banner. The films that followed are – Devdas, Madhumati, Sujata, Parakh, Yahudi, Bandini and Prem Patra. Eight more films came out of Bimal Roy Productions of which six were feature films – Amanat which Arabindo Sen was chosen to direct, Apradhi Kaun, a thriller, Pariwar, a family comedy, Usne Kaha Tha based on a Premchand short story, Kabuliwalla based on a Tagore short story, and Benazeer, starring Meena Kumari. The other two were documentaries – Gotama the Buddha and Swami Vivekanand, a biographical documentary he produced for Films Division.

“Bimal-da’s work is poetry in motion,” says music director Tushar Bhatia, classifying the music in Bimal Roy’s films into four categories – (a) as a cinematographer in New Theatres Studio, Calcutta, (b) as director in New Theatres Studio, Calcutta, (c) as an independent producer-director in Mumbai with Bimal Roy Productions and (d) as freelance director with production banners other than his own. “Bimal-da’s aesthetic sensibilities were shaped and honed in New Theatres which spilled over to the films he made in Mumbai,” says Bhatia, throwing light on background sound effects and the positioning and choreography of song situations in his early films. P.C.Barua’s Mukti was cinematographed by Bimal Roy in 1937. The film was path breaking in becoming the first ever film in history to use Tagore songs in cinema. A song from the film, “diner sheshe, ghoomer deshe” sung by Pankaj Mullick was the first Tagore song with the music composed by Mullick after obtaining clearance from Tagore himself. “The effects could be seen all over again in Salil Choudhury’s music for Bimal Roy’s Madhumati,” informs Bhatia.[i]

films into four categories – (a) as a cinematographer in New Theatres Studio, Calcutta, (b) as director in New Theatres Studio, Calcutta, (c) as an independent producer-director in Mumbai with Bimal Roy Productions and (d) as freelance director with production banners other than his own. “Bimal-da’s aesthetic sensibilities were shaped and honed in New Theatres which spilled over to the films he made in Mumbai,” says Bhatia, throwing light on background sound effects and the positioning and choreography of song situations in his early films. P.C.Barua’s Mukti was cinematographed by Bimal Roy in 1937. The film was path breaking in becoming the first ever film in history to use Tagore songs in cinema. A song from the film, “diner sheshe, ghoomer deshe” sung by Pankaj Mullick was the first Tagore song with the music composed by Mullick after obtaining clearance from Tagore himself. “The effects could be seen all over again in Salil Choudhury’s music for Bimal Roy’s Madhumati,” informs Bhatia.[i]

In terms of literature, in terms of characterization, in terms of capturing and freezing for posterity the ethnicity of Bengal, in terms of offering a unique world-view of a silent, peaceful spirit in cinema, Bimal Roy was an institution unto himself. Bimal Roy was one of the last iconoclasts Indian cinema has ever produced. Every single film from Bimal Roy films directed by Roy himself, had a social message interwoven into the script, or, the storyline itself was chosen on the basis of its social relevance. It was also chosen for the significance of the narrative itself. Thus, we find him banking again and again on literary classics of the country. From Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay to Munshi Premchand to Rabindranath Tagore, Roy’s films stand testimony to a celluloid transliteration of some of the immortal classics of Indian literature.

[i] Lecture-demonstration at Seminar on Bimal Roy at Nehru Auditorium, Calcutta, organised by Bimal Roy Memorial Trust, in a weeklong programme in January 2002.

Dr Shoma A. Chatterji is a freelance journalist, film scholar and author based in Kolkata. She has won two National Awards for Best Writing on Cinema—Best Film Critic in 1991 and Best Book on cinema in 2002. She won the Bengal Film Journalists Association’s Best Critic Award in 1998, the Bharat Nirman Award for excellence in journalism in 2004, a research fellowship from the National Film Archive of India in 2005–2006 and a Senior Research Fellowship from the PSBT Delhi in 2006–2007. She has authored 22 books on cinema and gender and has been a member of jury at several film festivals in India and abroad. She holds a master’s degree in Economics and in Education; PhD in History (Indian Cinema) and a Senior Research Post-doctoral Fellowship from the ICSSR. In 2009–2010, she won a Special Award for ‘consistent writing on women’s issues’ at the UNFPA–Laadli Media Awards (Eastern region), was bestowed with the Kalyan Kumar Mitra Award for ‘excellence in film scholarship and contribution as a film critic’ in 2010 and the Lifetime Achievement SAMMAN by the Rotary Club of Calcutta-Metro City in July 2012.

SAGE India: https://in.sagepub.com/en-in/sas/the-cinema-of-bimal-roy/book258442/

SAGE US: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/the-cinema-of-bimal-roy/book258442/

SAGE UK: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/the-cinema-of-bimal-roy/book258442/

© Dr Shoma A Chatterji