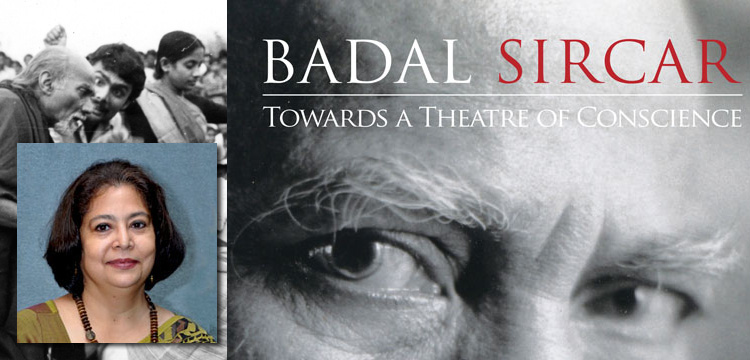

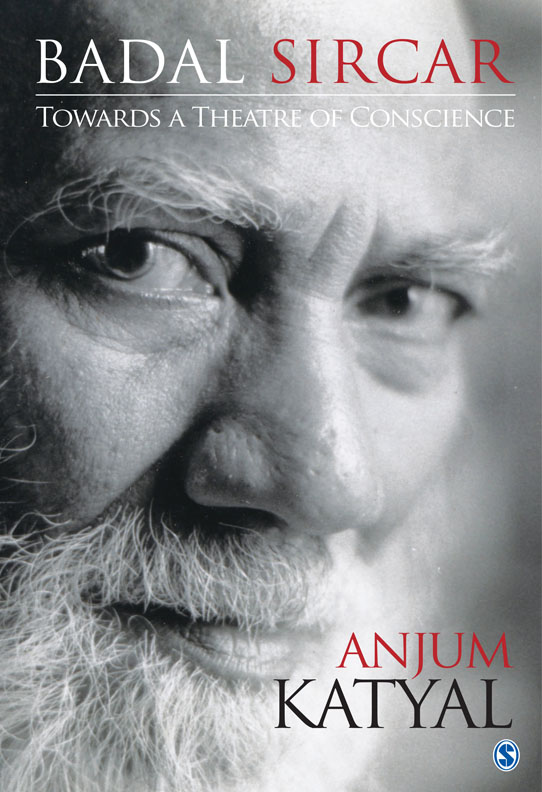

Encounters with Badal Sircar by Anjum Katyal,

author of Badal Sircar: Towards A Theatre Of Conscience. Published by SAGE

My first encounter with Badal Sircar – widely known as Badal-da in theatre circles – was through his theatre. This was in the early 80s, after my return to the city of Calcutta from college in the US. I had, of course, heard of his innovative and powerful Third Theatre, which was an alternative to the proscenium, with the actor central to all communication: if you were interested in cutting-edge arts and culture in India of the time, you had to have heard of Badal-da. So I went to see one of his regular weekly performances.

At the time, performances by Satabdi, Badal-da’s theatre repertory, were held in a large, rather rundown hall on the first floor of a building opposite the bustling New Market. Sindhi Association Hall. I climbed a bleak staircase and emerged onto a narrow verandah; attached was a large room. Unadorned, stark. Benches for the audience members. I took my place. I cannot remember which production I first saw but I remember being impressed. By the simplicity and fluidity of the action. This theatre was unlike anything I had previously encountered. Actors’ bodies turned into machines, bridges, furniture, forests. The message was strong and the sincerity palpable. It was up close and direct. Badal-da himself played a role, one amongst the ensemble actors. Grey bearded and balding, it was only his advanced age that signalled any distinction between him and his group members. Once the production ended, a piece of cloth was laid on the ground to collect the coins and rupees the audience could donated if they wished to. Badal-da briefly addressed the audience, announcing the weekly schedule and inviting us back if we liked the experience.

That was the first time I encountered him. Subsequently I watched Satabdi perform in the open air at Curzon Park, on the street, and in other public spaces. At the time they were in form, physically and in terms of conviction: fresh, lithe, effective.

It struck me, watching the group dynamics as they performed and interacted with the audience, that there was no ‘cult’ being created around him as an individual, no attempt by him or the others to project him as the leader or well-known figure he already was. Here, he was just part of Satabdi, participating in ensemble acting interchangeably with the other much younger men and women. The whole production was treated as a collective exercise. Clearly, Badal-da wanted it this way. My interest was well and truly caught.

By this time, Badal-da was already a controversial figure in the world of theatre as someone who had turned his back on his considerable achievements as a playwright and director of popular plays. Instead, he had committed himself and his group to a total rejection of the economy on which proscenium theatre was premised. He had proved through his practice of Third Theatre that it was possible to do meaningful, powerful and artistically evolved theatre on little or no money. This, and his own uncompromising stance, turned him into a bit of an outcast to the theatre fraternity. He was carving his own path, a cult figure to some, but also a loner. He attracted only those who believed in theatre as social commitment.

My second encounter with Badal-da was both more literary and more personal. I went to his home, at 1A Peary Row in north Calcutta. A narrow house in a narrow lane, a darkish room on the ground floor which doubled as rehearsal space, a few assorted and shabby pieces of furniture, scuffed wooden cupboards which he unlocked to produce slim volumes published by his group, for sale at modest prices.

The reason I was there was a professional one. Seagull Books, the publishing house where I was Editor, began bringing out his plays in translation. His essays on Third Theatre, the language of theatre, actor training, were to be translated and published as collections. Seagull Theatre Quarterly, which I edited, covered him in some detail. Given these multiple publication plans, I began to meet him at intervals to discuss the various projects. The Badal-da I encountered was always reserved, dignified, and focused on the task at hand. He didn’t chat or waste time on niceties. He had a wry, drily ironic tone at times, often self-deprecatory. Over several visits, he allowed a slight relaxation of tone to creep in. Towards the end of his life, when I paid what turned out to be a final visit, to interview him in connection with an article, I found him much more open to discussing a wide range of subjects related to his oeuvre. I quote from that section of my book:

“To the end he remained curious, interested, open to learning. I remember meeting him in 2009. By then his movements were restricted, and he was almost completely confined to his room in his house in north Kolkata. We spoke of several things, but what came through clearly was his deep passion for and commitment to the theatre path he had chosen to walk for the past forty odd years.” (Intro, p.xvii).

Because his self-respect was more important to him than publicity, this led him to disengage from the increasingly media-hungry, money-driven theatre scenario with which he was surrounded. I recall one telling incident which demonstrates this pride and self-respect. I was paying him a visit after a long break. In between he had had an accident, suffered serious injury, was home bound and unable to engage in his usual theatre and workshop activity. I carried with me a cheque from Seagull Books. As his publishers, this was entirely acceptable, but he balked at accepting it. He questioned me closely – why this money now? He did not need charity. Was this money due to him professionally? If so, for what exactly? He would not accept it unless he was sure that it was legitimately his due. Finally, only after he was assured that this was an advance against books in progress, would he allow me to hand it to him. I got a glimpse of the proud man who would not budge an inch from his principles.

This brings me to the third encounter with Badal Sircar. This happened some years after his death, when I began reading his memoirs while researching my book. A different Badal-da emerged from those pages: someone who enjoyed spending time chatting with friends; someone passionate and vulnerable, but always with a sense of ironic distance which stopped him from being pedantic; someone with a marked sense of humour; someone self-questioning and self-critical, continuously pushing his own boundaries. And then I began interviewing people who knew him well, who had worked with him closely. They spoke of him as an open-minded person who never put himself above them, who had no false pride: someone who became a student again at the age of 60, and attended MA classes alongside people younger than his own troupe members.

These multiple kinds of encounters helped me build a relationship with Badal Sircar more layered and complex than my direct interaction with him allowed. A relationship premised on respect for the man, whom I found admirably consistent in his values. A relationship based on the recognition that his contribution to the history of Indian theatre was significant and longlasting, and deserved to be studied, recorded and conveyed to future generations. A relationship of deep regard and appreciation for this remarkable artist who with little concern for self-promotion dedicated himself to bringing a meaningful theatre to the people.

————————

Anjum Katyal is Consultant (Publications), Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies (MAKAIAS), Kolkata and Co-Director, Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival. She has been the Chief Editor, Seagull Books, Calcutta (1987–2006) and Editor, Seagull Theatre Quarterly (1994–2004), as well as the Web Editor, Saregama-HMV (2006–11) and Editor, Art and the City, a web magazine on the contemporary arts in India (2010–13). As the editorial head of a specialist arts publisher, she was responsible for a broad range of books on art and culture between 1987 and 2006. She is the author of Habib Tanvir: Towards an Inclusive Theatre (SAGE, 2012). She has translated Habib Tanvir’s Charandas Chor and Hirma ki Amar Kahani (The Living Tale of Hirma), as well as Usha Ganguli’s Rudali and stories by Mahasweta Devi and Meera Mukherjee. She is translating Habib Tanvir’s Bahadur Kalarin. She has been involved in organising several exhibitions of contemporary art, as well as writing catalogues for exhibitions by Chittrovanu Mazumdar, Somnath Hore, Manu Parekh, Madhvi Parekh, Reba Hore and Nasreen Moochhala. She has a background in education and teacher training. A published poet, she also sings the blues, and writes on theatre and the visual arts.

Anjum Katyal is Consultant (Publications), Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies (MAKAIAS), Kolkata and Co-Director, Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival. She has been the Chief Editor, Seagull Books, Calcutta (1987–2006) and Editor, Seagull Theatre Quarterly (1994–2004), as well as the Web Editor, Saregama-HMV (2006–11) and Editor, Art and the City, a web magazine on the contemporary arts in India (2010–13). As the editorial head of a specialist arts publisher, she was responsible for a broad range of books on art and culture between 1987 and 2006. She is the author of Habib Tanvir: Towards an Inclusive Theatre (SAGE, 2012). She has translated Habib Tanvir’s Charandas Chor and Hirma ki Amar Kahani (The Living Tale of Hirma), as well as Usha Ganguli’s Rudali and stories by Mahasweta Devi and Meera Mukherjee. She is translating Habib Tanvir’s Bahadur Kalarin. She has been involved in organising several exhibitions of contemporary art, as well as writing catalogues for exhibitions by Chittrovanu Mazumdar, Somnath Hore, Manu Parekh, Madhvi Parekh, Reba Hore and Nasreen Moochhala. She has a background in education and teacher training. A published poet, she also sings the blues, and writes on theatre and the visual arts.

SAGE Website:

http://www.sagepub.in/books/Book248153

Infibeam:

http://www.infibeam.com/Books/info/9789351503705.html

Amazon:

http://www.amazon.in/s/?field-keywords=9789351503705