The Problem with Human Rights: Public Perception – Sophie Gallop, Doctoral Candidate and Teaching Associate, Birmingham Law School, University of Birmingham

The Problem with Human Rights: Who are human rights for?

A little over eighteen months ago I was staying with family after living and working abroad for a year. My parents’ next-door neighbour was catching up with me, and asked me what I was going to be doing next. In response to the fact I was about to start research in international human rights law, he turned around and disdainfully uttered “God, your parents must be so disappointed”. Unfortunately, he was being completely serious.

As December 10th and Human Rights Day approaches for 2015,[1] now seems a opportune time to reflect on the transformation of human rights over the last 65 years. Human Rights Day celebrates the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948,[2] the United Nations inaugural human rights charter. The UDHR was conceived in response to the atrocities committed both before and during World War II, and is one of the principal means by which the international community strove to ensure that such heinous incidents would never occur again.[3] Importantly, at the time, the UDHR was widely welcomed.[4] It was seen as a way to protect the rights and freedoms of every individual, regardless of their gender, race, religion, age, sexual orientation, political beliefs, or any other factor. Human rights existed for all of us, for the simple fact that we are all human.

Since then, however, there has been a significant shift in the international and public opinion of human rights. At present, human rights seem to be viewed by much of the European and American population with a degree of suspicion and animosity.[5] My neighbour’s opinion is not an anomaly; instead it seems to be the norm.[6] Why this has happened is hard to quantify, but in part it seems to be due to the phenomenon of ‘otherness’: the idea that human rights only apply to ‘other people’.[7]

At face value this may seem true: the average citizen in the United Kingdom or Western Europe will have little need to worry about his or her human rights being violated. Of course this is because, for the most part, those rights are already adequately protected, in part because of human rights decisions that have already been passed. It was a human rights decision that demanded all care homes must protect the rights of disabled residents, regardless of its local authority status. It was a human rights decision that ensured that individuals in homosexual relationships had the same inheritance rights as those in heterosexual relationships. It was a human rights decision that demanded that family members be involved in local authority decisions on care of a family member. Human rights decisions have already achieved a huge amount in the protection of individuals, much of which seems to have gone under the public radar.

Another reason that human rights have fallen into bad press goes beyond the phenomena of otherness. The British media has repeatedly correlated human rights with groups of people that society (often correctly) regards with animosity: prisoners, terrorists, and paedophiles etc.[8] Accordingly the feeling of otherness has been exacerbated by the impression on the public subconscious that human rights are there for the ‘bad guys’,[9] not for you, or I, or for the vulnerable in society.

It is of course true that members of ‘undesirable’ groups have benefitted from human rights protection. This is primarily because of their status as humans. As much as we may detest Abu Qatada and all that he stands for, his status as a human remains. Whilst we may not agree with the conclusions that human rights bodies reach in their interpretation of such rights, that those rights exist is indisputable.

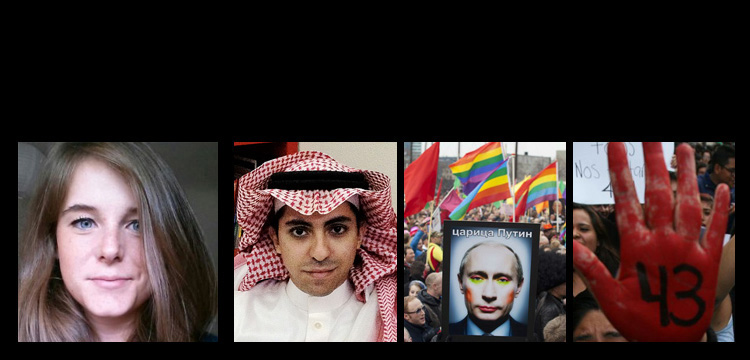

However, what is perhaps more relevant is that human rights are not just there for the bad guys. Human rights litigation has done a huge amount for many vulnerable groups; the disabled community, the LGBT community, and has drastically improved the rights of children in the UK. Further afield, 67 years after the creation of the UDHR, human rights violations occur each and every day, and each and every day vulnerable individuals find themselves in fear of their government. From the lashes being inflicted on Saudi blogger Raif Badawi,[10] to the forced disappearances of students in Mexico,[11] to the imprisonment of LGBT rights campaigners in Moscow and The Gambia,[12] human rights abuses continue to demand the protection of human rights law. The international community, however, cannot see the victims of these abuses, as the ‘bad guys’. We cannot, for example, in good conscience believe Mr Badawi to be bad because he questioned freedom of speech rights in Saudi Arabia.[13] We cannot believe the Mexican students who were training to be teachers ‘bad’,[14] and we cannot believe the LGBT activists in Russia to be bad because of their decision to protest the anti-LGBT propaganda laws.[15]

The phenomenon of the otherness seems to me to be a tacit acceptance of the fact that human rights standards have so far adequately protected the rights of many individuals. To see human rights as the reserve of others indicates that so far they have done their job for me. Furthermore, the idea those human rights are there solely for undesirable individuals, is a fallacy. Yes, human rights protect ‘bad’ people. That is not the real problem. The real problem seems to be the human rights public relations. Why is selective reporting of human rights cases so rampant? Why do newspapers seem to hate human rights on one hand, and cite ‘freedom of speech’ rights on the other?[16] The question at the start of this article was ‘who are human rights for?’ but the answer is clear: human rights are here for all of us. The real question is why do we not believe this?

The Problem with Human Rights: How are human rights implemented?

Another problem that has overshadowed the public attitude towards human rights is that of the perception of human rights implementation. There seems to unfortunately be a division in the perception and reality of human rights implementation throughout the World. On one hand it is clear that human rights abuses remain prevalent in many States; evidence of the fact that in many parts of the World human rights standards are not adequately enforced or ensured. On the other hand, the public perception in Western Europe seems to be that human rights are implemented with far too much vigour, thereby threatening to undermine domestic beliefs and values.[17]

To ensure that human rights standards are being implemented, the international community has a number of mechanisms to monitor each State. The United Nations utilises the Universal Periodic Review,[18] which demands that each State submit a report to the relevant human rights body at timely intervals, detailing how human rights standards are being respected in that State. Additionally United Nations Human Rights covenants, and other regional human rights instruments such as the European Convention on Human Rights and the African Convention on Human and Peoples’ Rights, allow individual complaints to be made to international human rights bodies.[19] This permits any individual who alleges to have had their human rights violated to make a personal application[20] to the relevant human rights body, which will examine the allegation and give a decision on whether a violation did actually occur.

The individual complaints procedure, especially that under the European Convention of Human Rights, has received a lot of attention in the British media. It was this mechanism that allowed complaints to the European Court from prisoners regarding their right to vote,[21] and alleged terrorist Abu Qatada to challenge his extradition to Jordan.[22] Public perception of the individual complaints mechanism seems, unsurprisingly, to mirror that of the British media. In a recent poll the majority of those questioned from the British public felt that the application process under the Human Rights Act has been taken advantage of by individuals.[23] This belief is exacerbated by the fact that the majority of those questioned also believed that the only individuals who benefit from human rights didn’t deserve them.

Yet the human rights that so often make the headlines have, in practice, a much narrower impact than the media might imply. The rights typically associated with the European Convention (civil and political rights) are not rights that States have to take active steps to ensure; instead, they are rights that the State has to prevent from being violated. The majority of these rights can be viewed as ‘freedoms from’ rather than ‘rights to’, for example freedom from torture, from forced disappearance, from death, from arbitrary imprisonment etc.

Despite the pervasive perception that human rights standards are implemented with too much vigour, there are several procedural mechanisms that protect national sovereignty and prevent human rights bodies being inundated with individual complaints of human rights abuses. One such mechanism is the domestic remedies rule. The exhaustion of domestic remedies rule demands that any application by an individual to an international tribunal should be rejected, until such a time as the individual exhausted all domestic remedies available to them in the country where the violation was alleged to have occurred.[24] There are only limited circumstances when the individual may circumvent the exhaustion rule, and make a complaint directly to the human rights body. The result is that individuals who allege human rights violations must not only make a complaint to the domestic courts in the State alleged to have committed the violation, but also exhaust any administrative remedies (such as national human rights commissions) available.

The exhaustion of domestic remedies rule is alleged to fulfil a number of functions. Firstly, it blocks too many application reaching international human rights bodies, to prevent them from being overwhelmed. Secondly, it protects State sovereignty, and allows States to do justice in their own way, whilst ensuring the domestication of international human rights standards. Thirdly, it protects the individuals from costly litigation. Whatever functions the rule serves, however, it has been one of the most significant barriers for individual complainants seeking to reach international human rights bodies. 92% of the individual applications to the European Court of Human Rights in 2013 were rejected for being inadmissible,[25] and States almost unfailing cite non-exhaustion of domestic remedies, sometimes without even regarding the facts of the complaint, as a reason that the human rights body should reject a case.[26]

Despite the reality that only a minority of cases (some have estimated as low as 1% of cases[27]) are declared admissible and examined by human rights bodies, the belief that human rights are implemented with too much vigour remains. That human rights violations remain so prominent around the World and that statistics on admissibility are so low, both fly in the face of this assumption. How can there be too much of implementation of human rights standards when so many horrific human rights abuses continue? How can there be too much of implementation of rights, when comparatively so few individual applications are able to reach the international human rights body which is supposed to examine them? Once again it seems that it the real problem with human rights is it’s public relations.

The perception of human rights has undeniably changed. But what human rights seek to achieve has not. That we are all human and all entitled to be free from particularly heinous treatment remains true. What has failed is this message. The media focus on prisoners, terrorists, and other ‘bad guys’ means that much of the public has lost the understanding of what the true goal of human rights. Human rights are there for all of us, particularly those who, whether by their own actions or not, are vulnerable. We give all people those rights because we aspire to be a society who treats all persons with respect, whether that person is a prisoner or an activist, a terrorist or a disabled person, a murderer or child.

We know that the more that people are educated about human rights, the more positive they tend to feel about them.[28] But we also know that there seems to be a huge amount of negative press coverage about who human rights are for, and how invasive they are on public life. The problem is not what human rights are doing and what they seek to do, but with how we perceive those human rights. The sad reality is, the human rights’ public relations machine has stalled, and without it human rights are under threat; for me, that is the real problem.

————————-

[1] United Nations’ ‘Human Rights Day 2014: #Rights365’ (United Nations 2014). Available at <http://www.un.org/en/events/humanrightsday/> accessed 19 October 2015.

[2] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (adopted 10 December 1948 UNGA Res 217 A(III) (UDHR)

[3] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights ‘History of the Document’ (United Nations 2015). Available at <http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/history.shtml> accessed 19 October 2015.

[4] Ibid

[5] See generally Alice Donald, Jane Gordon and Philip Leach ‘Research Report 83: The UK and the European Court of Human Rights’ (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2012). Available at <http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/documents/research/83._european_court_of_human_rights.pdf> accessed 19 October 2015.

[6] Ibid

[7] Kully Kaur-Ballagan, Sarah Castell, Kate Brough and Heike Friemert ‘Public Perceptions of Human Rights’ (Equality and Human Rights Commission 2009). Available at <http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/publication_pdf/public_perceptions_of_human_rights_ipos_mori.pdf> accessed 19 October 2015, 57

[8] Donald at al. (n5), 25; Alice Donald, Jenny Watson and Miamh McClean ‘Research Report 28: Human Rights in Britain since the Human Rights Act 1998: A Critical Review’ (Equality and Human Rights Commission 2008). Available at <http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/documents/human_rights_in_britain_since_the_human_rights_act_1998_-_a_critical_review.pdf> accessed 19 October 2015.

[9] Kaur-Ballagan et al. (n7), 57

[10] Ian Black ‘A Look at the Writings of Saudi blogger Raif Badawi – sentenced to 1,00 lashes’ (The Guardian, 14 Jaunary 2015). Available at <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/14/-sp-saudi-blogger-extracts-raif-badawi> accessed 19 October 2015.

[11] Harriet Alexander ‘What has happened to the missing Mexican students, and why does it matter?’ (The Telegraph, 26 September 2015). Available at <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/centralamericaandthecaribbean/mexico/11447419/What-has-happened-to-the-missing-Mexican-students-and-why-does-it-matter.html> accessed 19 October 2015.

[12] The Council for Global Equality ‘Facts on LGBT Rights in Russia’ (Council for Global Equality, 2015). Available at<http://www.globalequality.org/newsroom/latest-news/1-in-the-news/186-the-facts-on-lgbt-rights-in-russia> accessed 19 October 2015; The Guardian ‘Gambian leader approves anti-gay law’ (The Guardian, 2015). Available at <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/21/gambian-leader-approves-anti-gay-law> accessed 19 October 2015.

[13] Ian Black ‘A Look at the Writings of Saudi blogger Raif Badawi’ (n10)

[14] Harriet Alexander ‘What has to the missing Mexican student…’ (n11)

[15] The Council for Global Equality ‘The Facts on LGBT Rights in Russia’ (n12)

[16] See generally Mick Hume ‘How free speech became a thought crime: a chilling warning after feminists hound a Nobel winner from his job for ‘sexism’ (Daily Mail, 20 June 2015). Available at <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-3132206/How-free-speech-thought-crime-chilling-warning-feminists-hound-Nobel-winner-job-sexism.html> accessed 19 October 2015.

Daily Mail Comment ‘A Nation Imperiled by the Human Rights Act’ (The Daily Mail, 1 August 2015). Available at <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-3181945/DAILY-MAIL-COMMENT-nation-imperilled-Human-Rights-Act.html> accessed 19 October 2015.

[17] ‘A Nation Imperilled by the Human Rights Act’ Ibid.

[18] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights ‘Universal Periodic Review’ (United Nations Human Rights, 2015). Available at <http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/UPR/Pages/UPRMain.aspx> accessed 19 October 2015.

[19] Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (European Convention on Human Rights, as amended) (ECHR), Article 34; Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (adopted 16 December 1966, entered into force 23 March 1976), 999 UNTS 171; African Convention on Human and People’s Rights (1966) OAU Doc. CAB/LEG/67/3 rev. 5, 21 I.L.M. 58 (1982)

[20] They can also be represented by an NGO or family member

[21] Hirst v United Kingdom (No 2) [2005] ECHR 681

[22] Othman (Abu Qatada) v United Kingdom [2012] ECHR 8139

[23] Donald et al. (n5), 25

[24] Sophie Gallop ‘The Exhaustion of Domestic Remedies Rule: A Realistic Demand for Individuals who have Suffered Torture at the Hands of State actors?’ (2013) Bristol Law Review 75, 78

[25] European Court of Human Rights ‘Practical Guide on Admissibility Criteria’ (European Court of Human Rights, 2014). Available at <http://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Admissibility_guide_ENG.pdf> accessed 19 October 2015.

[26] Udombana ‘So Far, So Fair: The Local Remedies Rule in the Jurisprudence of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ (2003) 97(1) AJIL 1, 20

[27] Weil ‘Decisions on Inadmissible Applications by the European Commission of Human Rights’ (1960) 54(3) AJIL 874, 874

[28] Ministry of Justice ‘Research Series 1/08: Human Rights Insight Project’ (Ministry of Justice, 2008). Available at <http://www.equality-ne.co.uk/downloads/153_human-rights-insight-part1.pdf> accessed 19 October 2015.

————————

Sophie Gallop completed her LLB, with honours, at the University of Warwick in 2012, and then her LLM at the University of Bristol in 2013. Sophie additionally undertook work as a Legal Assistant during my studies. The LLM was focused on international law, and her dissertation focused on the effects of the exhaustion of domestic remedies rule on individual applications alleging torture to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. During completion of the LLM, Sophie additionally took part in the John Davis project.

After the completion of the LLM, Sophie was offered a position as a Visiting Lecturer at the University of The Gambia, through the Bristol Human Rights Implementation Centre. At the University of the Gambia, she lectured Contract Law, Tort Law and Legal Ethics. Additionally Sophie was a member of the University of The Gambia Working Group on Academic Affairs engaged in improving the legal curriculum and working practices at the University, and a personal tutor to a number of first year students.

Currently Sophie is a teaching associate and PhD candidate at the University of Birmingham. Her doctoral research is focused on the relationship between examples of non-independent judiciaries and incidents of torture, and the effect that relationship has on individuals attempting to exhaust domestic remedies in the context of individual applications of torture to the Human Rights Committee, under the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Sophie has previously written on human rights issues including the flogging of Raif Badawi, and the status of LGBT rights in The Gambia. An article on the effect of the exhaustion of domestic remedies rule in the Africa human rights system is forthcoming.