On Education in India by Professor Ganesh Devy, Chair, People’s Linguistic Survey of India. He has been awarded the Padmashree by the Government of India (2014), the Prince Claus Award (2003) for his work for the conservation of craft and the Linguapax Award of UNESCO (2011).

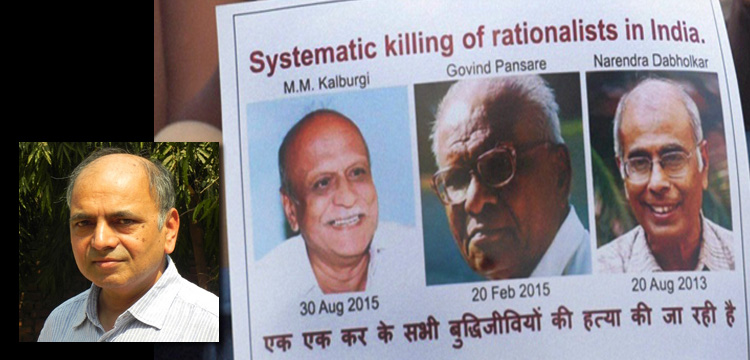

As a prelude to the article that Professor Ganesh Devy has generously contributed we have added a news report from India that reflects a growing unease amongst the intelligentsia of rising intolerance often leading to murder.

———————

Gujarat’s renowned tribal activist Ganesh Devy on Sunday (11th October 2015) joined the brigade of other eminent writers in the country who have returned their Sahitya Akademi Awards. Here is an excerpt from his letter addressed to Sahitya Akademi’s president Professor Viswanath Pratap Tiwari and vice president Dr Chandrashekhar Kambar. Devy said he is returning the 1993 Sahitya Akademi Award which was conferred upon him in the category of books in English for his 1992 work After Amnesia.

“When I gave the Gokak lecture, Dr. Kalburgi was still alive. Alas, he had to fall to the forces of in-tolerance. A week after his killing, I participated in a Seminar organized by the Sahitya Akademi. This was in Nagpur. I was to preside over the Inaugural Session. I was quite dismayed to see that the seminar began without a word of reference to the recent attack on a scholar honoured by the Akademi. Therefore, when my turn to speak came at the end of the session, I asked the audience if they would object to my observing a two minute silence to mourn the dastardly killing. Please note that all of them stood up in silence with me. If our writers and literary scholars had the courage to stand up in Nagpur, I fail to understand why at the Ravindra Bhavan there should be such a deafening silence about all that is happening to free expression in our country. I have personally known both of you as my seniors and have admired your writings and imaginative powers. May I make bold to say that your moment of reckoning has come? I hope you will give this country the assurance that it is the writers and thinkers who have come forward to rescue sense, good-will, values, tolerance and mutual respect in all past ages. Had this not been so, why would we be remembering the great saint poets who made our modern Indian languages what they are today? The great idea of India is based on a profound tolerance for diversity and difference. They far surpass everything else in importance. That we have come to a stage when the honourable Rastrapatiji had to remind the nation that these must be seen as non-negotiable foundations of India should be enough of a reason for the Sahitya Akademi to act.,” reads letter of Devy, who is also a Padma Shri awardee and Unesco Linguapax laureate.

———————

Though somewhat old fashioned, one of the several perspectives on education is that it is all about knowledge. There have been other perspectives too that held sway in different phases of human history. For early man it was probably of prime importance for the very survival. In ancient times, after humans entered the agricultural mode of civilization, it came to be respected as a repository of collective memory. Much later, it acquired the function of training young minds, perhaps in the interest of preserving social order or simply because the collective memory had by then gained autonomy. For the last few centuries, education has become a scrutiny regime that a young one must imbibe in order to be socially acceptable, economically productive and politically non-volatile. Just as the objectives of education have kept changing through history, the formal arrangements for its transmission and reception too have passed through transitions from epoch to epoch.

In our time, education is once again facing the need for a complete metamorphosis. Often, the ‘sea-change’ so rapidly taking place in the human idea of education is placed along the question of knowledge. Thus, Lyotard’s analysis of the post-modern condition proposed a wide scattering and utter fragmentation of knowledge in the twenty-first century into ‘knowledges’ pegged on not analogy but what he called ‘paralogy’. Throughout the last quarter of the twentieth century, a large array of theory went into the archeology of knowledge in order to highlight the epistemic shift in human knowledge being witnessed.

Two major factors – at least the most visible and the easiest to grasp, as well as with an unusual power to hurt or to please—made their presence felt precisely at the same time when the established idea of knowledge was going through a seismic shocks. One, the post cold-war western economies started unleashing an unprecedented disinvestment tendency in the field of education, and two, a development in the field of artificial intelligence and chip-based memory started questioning the content in established educational practices. Thus, the governments that were keen on cutting public costs on education and institutions that were keen on cutting some of the more traditional fields of knowledge from the gamut of institutional education became the order of the day. While this was happening in the west, and surely as a fall out in the countries that had accepted the idea of a universal knowledge and, therefore, a ‘universal idea of education’, some of the UN agencies had been raising serious alarm on the plummeting development index in the global South.

Thus, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, in countries like China and India, there appeared a mixed and fairly confused situation in the field of education. On one hand, the number of universities multiplied as never before in history; on the other, governments actively promoted the idea of education as a kind of industry that cannot be developed without private enterprise. Lo and behold, in India, if one had been talking of a hundred and thirty universities at the beginning of the decade, by its end the number was in four digits. We have today several categories of universities: national universities, central universities, state universities, deemed universities, open universities, private universities and foreign universities operating through franchise arrangements, some of these as large as enviable industrial empires and others tiny as lap-top shops. Add to these, nearly sixty thousand institutes of tertiary technical education. This should be otherwise a thing to welcome, except that the phase of this explosion of institutions has precisely been the phase of the state’s accentuated withdrawal from the field. The UPA governments trod this path and the present government is treading it likewise. The torrential invasion of ICT and the drying up of the state patronage provided to all fields and disciplines of knowledge have, together, created new rapids, new pitfalls, new puzzles and new unfilled spaces in the field of education in India. Here is a random and a merely symptomatic snap-shot of the ‘news’ in the field.

The country has watched on television and read in newspapers the gruesome and blood curdling scam involving tens of thousands of young persons whose education was not equal to the requirement of intellectual competence expected of them. So they went out seeking relief through impersonation, bribery, cheating and just simply falling pray to greed and murderous crime. If this shameful and horrifying scam took place in a short calendar space, the intellectual and moral rot atop which it stands has been around for quite a while. Saying this not a defense of the scamsters –vicious as they are—but a necessary comment on the larger scale tragedy and deception of which the young in India are the hapless victims. Add to this sordid tale of mockery of knowledge by the mediocrity and greed witnessed on the campus of practically every university and research institution. Add also the neglect of several key fields of knowledge and academic disciplines that makes knowledge generation hugely lop-sided and heavily laden with the idea of ‘knowledge for profit.’

The decay and decline of the idea of a knowledge institution is worsened by frequent intimidation and brow-beating of institutions that still care to produce thought and raise challenging questions.

This show of raw strength matches the show of unmasked affection for the like-minded or the kinship-blessed when it comes to offering academic positions. If these happen to be key-posts, they are perceived now as unquestioningly political positions; and going by this principle, interference in the autonomy of knowledge institutions is seen as the constitutional prerogative of the regime.

It does not matter then if the institution in question is any prestigious institute of technology, university, national academy, museum, research council or a public body for research and teaching. The principle is simple: if we pay for you, you shall play the tune of our choice. No matter if the tune hurts the foundations of knowledge, if it diminishes the quest for search and destroys the ability to raise new and meaningful questions that go into making education a pursuit of knowledge. It is as if knowledge no longer is the heart of education.

When one looks at the snap-shot drawn together here, I am woefully aware that it is more a selfie rather than a sting clip. As someone involved in universities and research over the last four decades, I feel amply guilty for the state of education in India. I should also add that despite the sickening snap shot of the field, there are innumerable individuals and numerous exceptional institutions that have shown brilliance and contributed to furthering research and advancement of knowledge. However, it is the presence of these individuals and such institutions that makes the point even more pertinent. Has there prevailed a general atmosphere of institutional autonomy and respect for new ideas and thought, these numbers could have been much larger than the numbers associated with the public examination scams. The point really is that academic excellence does not appear to be the goal post for education.

If we step a little back in history, we notice that from the beginning of the nineteenth century, every major Indian thinker, social reformer, scientist and writer has grappled with the question of education for modern India. These ‘makers of India’ include not just Tagore, Gokhale, Tilak, Gandhi, Aurobindo, Ambedkar, and such historically more visible personalities but also those, relatively less visible such as Sayajirao Gaekwad in Gujarat, Bhaurao Patil and J. P. Naik in Maharashtra and Mahatma Hansraj in the north, and those others who set up village level schools or high schools and colleges in various cities through the length and breadth of India. The fact of Indian history is that the modern education in India has not been just a public institutional system set up only or primarily by the state. It is also a cultural product for creating which a very large number of selfless individuals have given their all.

Therefore, their vision and creation cannot be seen as a government undertaking ready for disinvestment when such a move suits the economy. Unfortunately, after independence, none of the greater visions of education suitable for sustaining the innate strengths of the Indian society got organically integrated with education, particularly the higher education in India. The idea of producing engineers and doctors as man-power for economic development gained predominance, and all of the secondary school education got bogged down under its crushing pressure. The English language alone was seen as the language of knowledge; and the easier access to employment for those who access to the English language drove the entire primary school education too inexorably to the learning of English.

Though there is nothing wrong with the idea of schooling through the English language per say, it is a scientifically established fact that education in one’s mother tongue gives young learners a far greater ability to grasp complex abstract concepts. So, all in all, we have now millions of children who simply drop out because there is nothing in school that can hold them back. Those who continue have to study in a manner such that their ability to think originally is systemically curtailed at an early age. When they cross the school age and move to higher education, the institutional rot there leaves little space for them to acquire any genuine intellectual interest, let alone research skills. The college level institution too defines ‘success’ in terms of ‘placements for jobs’ and how high the graduates can draw as their first salary. What about knowledge, thinking, questioning, reasoning, quest, research and pursuit of truth? Well, they are the marginalized beings in the arena of the human resource development. Not good news for the nation, nor for the humanity.

Under these circumstances, the state needs to take a real hard look at the situation of the schools and the idea of schooling itself. One is aware that this easier said than done. Yet, the need can be ignored only at our collective peril. What can be sadder than the fact that the primary school teacher’s job is the very last on the priority list of the educated young persons in India? Instead of turning this woeful situation around, we are collectively forcing the school teacher to tow the political line—whether in Bengal or in Uttar Pradesh or in Gujarat. Similarly, the state support to the universities and institutions should be entirely merit based.

What great good did the Communist regime in the former USSR or China do to development of research by forcing the academic community to subscribe the doctrine? What good did the Iranian government do to its universities by forcing only the Islamic vision of knowledge on the professors and writers in Iran?

What great good shall the present government in India do by expecting academics to subscribe only a certain understanding of history or culture? History has more than ample testimony that such moves result in emasculation of the intellectual capital in a given society.

Nationalism and a genuine respect for the cultural past will emerge if the young minds are exposed to all ideologies, all versions of truth and then encouraged to decide on their own what is worth respecting and what worth discarding. Not even the best among the Indian universities are able to create and nurture such an intellectually vibrant ethos. Besides, if you try to be vibrant and that vibrancy is going to be termed as anti-state, none but a few shall ever make the attempt. In the process, India will be the loser. Finally, disinvestment may be a principle worth trying out, or it may even a dire need of the hour, but if the privately invested institutes drive entire education to the single goal of material success, safeguarding and nurturing the materially less attractive branches of knowledge should become one of the top priorities of the state.

Disinvestment – even when it bears the attractive name of public-private-partnership – without the ‘knowledge responsibility’ for the materially non-gainful disciplines may become the last nail in the coffin of ‘knowledge’. If the principle of corporate social responsibility can be invoked for improving the access of those made vulnerable by the processes of globalization, why can the government not impose the responsibility of setting a chair of philosophy or aesthetics, or music or linguistics in a state university on the private technology and management universities that are today free to make profits out of education? If our education keeps drifting aimlessly, and is assessed purely quantitatively, if it is pressurized to follow only certain ideologies rather than giving it a chance exposure to all ideologies, ‘isms’ and perspectives, if the public institutions built through people’s sacrifice and public funds are not allowed their dignity and autonomy, will India be able to stand with pride in the global arena of knowledge?

All of us need to reflect on these questions, and most of all those whose responsibility it is to give to young Indians what they deserve as citizens of a great democratic country marked by its heritage and its diversity. It is time that the attention shifts from petty attempts to intimidate and silence dissent, and from the covert or overt indoctrination, to the question of Indian education as a collective national challenge.

——————–

Professor G. N. Devy, was educated at Shivaji University, Kolhapur and the University of Leeds, UK. He has been professor of English at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, a renowned literary critic, and a cultural activist, as well as founder of the Bhasha Research and Publication Centre at Baroda and the Adivasi Academy at Tejgadh. Among his many academic assignments, he has held the Commonwealth academic Exchange Fellowship, the Fulbright Fellowship, the T H B Symons Fellowship and the Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship. He was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award for After Amnesia, and the SAARC Writers’ Foundation Award for his work with denotified tribals. His Marathi book Vanaprasth has received six awards including the Durga Bhagwat memorial Award and the Maharashtra Foundation Award. Similarly, his Gujarati book Aadivaasi Jaane Chhe was given the Bhasha Sanman Award. He won the reputed Prince Claus Award (2003) awarded by the Prince Claus Fund for his work for the conservation of craft and the Linguapax Award of UNESCO (2011) for his work on the conservation of threatened languages. In January 2014, he was given the Padmashree by the Government of India. He has worked as an advisor to UNESCO on Intangible Heritage and the Government of India on Denotified and Nomadic Communities as well as non-scheduled languages. He has been an executive member of the Indian Council for Social science Research (ICSSR), and Board Member of Lalit Kala Akademi and Sahitya Akademi. He is also advisor to several non-governmental organizations in France and India. Recently, he carried out the first comprehensive linguistic survey since Independence, the People’s Linguistic Survey of India, with a team of 3000 volunteers and covering 780 living languages, which is to be published in 50 volumes containing 35000 pages. Devy’s books are published by Oxford University Press, Orient Blackswan, Penguin, Routledge, Sage among other publishers. His works are translated in French, Arabic, Chinese, German, Italian, Marathi, Gujarati, Telugu and Bangla. He lives in Baroda.

© Professor Ganesh Devy