Will China Export its Water Crisis? by Nimmi Kurian, Associate Professor at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, India.

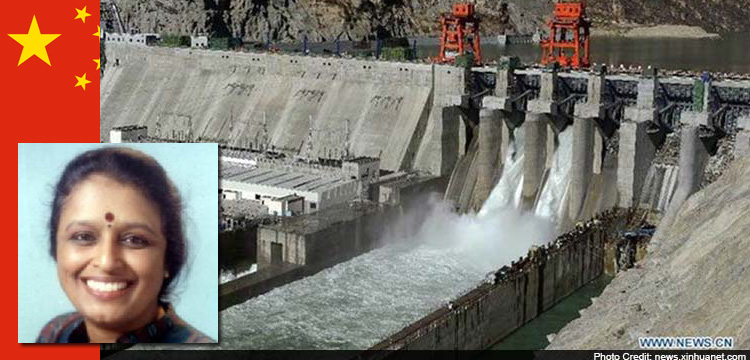

The signs of water crisis are everywhere in China. From declining freshwater reserves, increasing droughts, desertification levels and a vulnerability to sandstorms, the browning of China is both real as well as stark. China is witnessing a virtual dam-building boom with a concerted national campaign to develop and augment the country’s huge hydropower capacity. As China’s largest hydroelectric dam on the Brahmaputra (Yarlung Tsangpo) became fully operational in October this year, it has triggered a renewed bout of fear and paranoia in India. The $1.5 billion Zangmu hydroelectric dam as well as 39 run-of-the-river projects on the Yarlung Tsangpo and its tributaries has raised questions about the likely transborder implications of China’s resource choices. The fact that three of these dams, the Jiexu, Jiacha and Zangmu dams are within 25 kms of each other and at a distance of 550 kms from the Indian border has further stoked downstream concerns.

It is easy to understand why. Having already built more than 25,800 dams, China is embarking on an ambitious programme to nearly double its hydropower generation to 380,000 MW by 2020. Much of China’s hydropower expansion is based on augmenting capacity in its Western region, which is being projected as the energy powerhouse of the country. Within the western region, the provinces of Tibet and Yunnan are emerging as focal points of hydropower expansion with a series of dams being planned on major international rivers such as the Salween, Mekong and the Yarlung-Tsangpo. As the headwaters of many of Asia’s mighty rivers, the Tibetan ‘water bank’ in every sense becomes Asia’s water bank and the environmental sustainability of Tibet means the environmental sustainability of much of Asia. Many of these rivers flow into some of the most populous regions of South and Southeast Asia. There are growing concerns in the region that construction of dams by China could adversely impact flows downstream. For instance, when runoff levels fall substantially during the lean season, levels of vulnerability among downstream communities are likely to be heightened significantly. Changes in the hydrology of glacier-fed rivers also raise fears of flash floods and dam safety.

Added to these are concerns that the fragile ecosystem of the Tibet-Qinghai plateau is showing other signs of stress as it struggles to cope with the furious pace of economic activity that forms part of China’s Western Development Strategy. The ‘pillar’ industries of mining and timber processing have fed the rapid industrialisation of Tibet, bringing in its wake assorted problems of deforestation, soil erosion, landslides, floods, acid rain and pollution especially of the water systems. These are creating ecological imbalances in the form of rising temperatures, retreat of glaciers and droughts caused by indifferent rainfall. Chinese researchers have estimated that average temperatures on the Tibetan plateau have been rising by 0.31 degree Celsius every decade based on an analysis of climate change data collected between 1961-2013. This is reported to be 10 times the national average and thrice the rate of global warming. The average annual mean warming in Asia is expected to rise from 3 degree Celsius in the 2050s to 5 degree Celsius by 2080s as a result of a concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. There are growing fears as many of these ecological imbalances in the form of rising temperatures, retreating glaciers and droughts caused by indifferent rainfall are increasingly finding their way to parts of the extended subregion. Climate change is exacerbating the spatial and temporal variations in water availability, with the annual runoff in mega deltas such as the Brahmaputra and Indus projected to decline by 14 per cent and 27 per cent respectively by 2050. This will have significant implications for food security and social stability given the impact on climate sensitive sectors such as agriculture. There is also growing concern that transboundary dam projects are blocking fish migratory routes and fish production. For rural riparian communities this spells nothing short of a food crisis since fish constitutes a chief source of food and their principal source of protein. These will also entail troubling trade-offs between hydropower, food security and biodiversity will have ripple effects across the transboundary basin. In neighbouring Mekong there is growing concern that transboundary dam projects are blocking fish migratory routes and fish production.

Many of these concerns get further compounded by the fact that India’s official narrative has largely tended to downplay many of these concerns. For instance, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh summarily chose to dismiss these fears when he informed the Rajya Sabha in 2011 that India ‘trusts China’ and relayed China’s assurance that ‘nothing will be done that will affect India’s interest’. Not surprisingly, there is growing consternation in the Northeast on what is widely perceived as the Centre’s lack of resolve in raising the issue with China. It has also not helped that while India and China have signed agreements for the sharing of flood-forecasting data, India does not have any water-sharing treaty with China. For instance, Assam’s Chief Minister Tarun Gogoi tersely noted recently, “Construction of big dams will adversely affect downstream areas of Assam and the north-east region and I fail to comprehend why the Centre is not taking the matter seriously despite knowing this fact.” These concerns are further exacerbated by the fact that there are currently no platforms to institutionalise regular interactions between the Centre and the Northeastern border states on many of these cross-cutting issues. For instance, the Interstate Council (ISC), a forum designed to bring all Chief Ministers to work on operationalising coordination mechanisms between the Centre and the states has only held two meetings so far, the last one being held in December 2006. Centralised agencies such as the Brahmaputra Board under the Ministry of Water Resources have also shown the limits of a top-down model that does not seek to involve active cooperation with the states. There are also as yet no forums for engaging in an institutionalised dialogue with the 39 MPs from India’s Northeast.

The fact that many of these transboundary challenges are experienced at the local level calls for finding effective ways of incorporating border regions into India’s engagement with China on transboundary waters. Given the multiple ripple effects, transboundary water governance issues rightly need to be conceived as regional public goods that require transnational frames as against the bilateral frames. Can we frame some of these questions in ways that can create institutional entry points for a whole set of missing issues that currently are invisible to the mainstream policy and research gaze in India and China? India and China’s willingness to begin a subregional conversation on regional public goods could pave the way to designing norms of benefit sharing, negotiating trade-offs, and allocating risks and burdens on collective goods and bads in the region. It remains to be seen if India and China can indeed cross the river by feeling the stones.

—————–

Nimmi Kurian is Associate Professor at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, India and India Representative, India China Institute, The New School, New York. Her research interests include border studies, India-China borderlands; approaches to regionalism; transborder resource governance particularly water. Her recent publications include: The India China Borderlands: Conversations Beyond the Centre, Sage, 2014; “Building Half Bridges? India’s Northeast and the ‘New’ Reading of Borders”, Man and Society: Journal of North-East Studies, Vol. Xi, Winter 2014; “Uncharted Waters: Navigating the Downstream Debate on China’s Water Policy” in K. J. Joy et al eds, Compendium on Water Conflicts in Northeast India (Forum for Policy Dialogue on Water Conflicts in India, Pune, 2013) and “Subregionalising IR? New Frames for the India-China Borderlands”, in L. H. M. Ling (ed.), Rethinking Borders and Security, India and China: New Connections for Ancient Geographies, (University of Michigan Press, 2015, forthcoming).

http://www.uk.sagepub.com/books/Book242309

http://www.amazon.in/India-China-Borderlands-Conversations-beyond-Centre/dp/8132113519

http://www.amazon.com/India-China-Borderlands-Conversations-beyond-Centre/dp/8132113519

http://www.flipkart.com/india-china-borderlands-conversations-beyond-centre-english-1st/p/itmdvun9ctdybxg6?pid=9788132113515&q=9788132113515

http://www.infibeam.com/Books/info/9788132113515.html