Building homes while Affirming Rights: How the housing movement is changing Brazilian Urban Landscape by Mariana Prandini Assis, The New School for Social Research (New York).

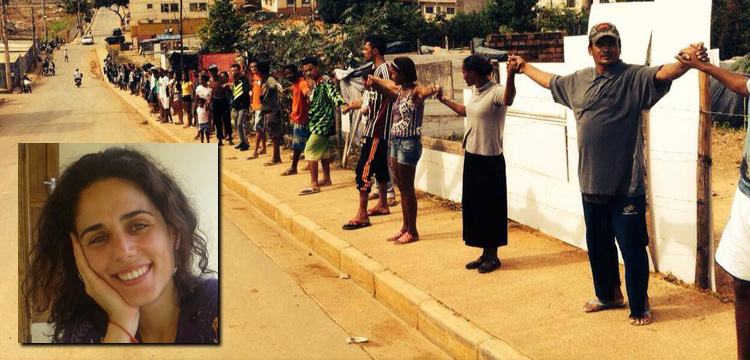

(Photograph of people holding hands by Occupation Izidora, in Santa Luiza/MG)

“We do not want the right to housing. We want housing.” This is how Brazilian homeless families express their grievance, and denounce the gap between ‘the law in the books’ and ‘the law in action’. By doing so, rather than abandoning the grammar of rights, they instead demand that these are taken seriously and made reality. Taking a step even further, they move beyond claims, and make rights real through their political action: by occupying vacant buildings and land, thousands of homeless families are breaking the real state speculative bubble and building their homes. In this process, not only the legal discourse is central to their political activism but also courts have become a crucial space where their fate is decided.

The use of legal discourse and strategies by social movements to advance their goals has long been an important concern for both scholars and activists. The reliance on legal institutions, such as national or international courts, continues to foment critical questions that include, but are not limited to, the role of (legal) experts in movement processes, the appropriate language for political mobilization, the tension between institutional tactics and larger movement building, and the trade-off between short-term victories and deep structural transformations.

Early scholarship on the issue tended to be rather skeptical about the role and capacity of litigation or any other legal strategy in promoting social change. Galanter (1974) and Kairys (1998), for example, suggested that “law is biased towards the status quo”, and therefore operates as to reinforce exclusions and social hierarchies.[1] In addition, scholars such as Scheingold (2004) and Handler (1978) claimed that, as “a conservative strategy dominated by elites”, litigation would only capture energy and efforts that could otherwise be used for more effective, transformative and grassroots organizing.[2] In this sense, this first assessment is marked by a strong anti-law/rights position: it admonishes social movements on the myth of rights and the illusions created by the liberal creed that it is possible to achieve deep social change through the legal system.

Despite my agreement with some of the claims above, particularly those that stress the elitist and thus conservative character of the legal institutions, I still want to argue that the legal system has fissures through which an insurgent, therefore transformative, discourse can emerge and develop. In what follows, I attempt to demonstrate this claim by giving a picture of the current urban landscape in Brazil and the struggles for housing that unfolds in it. I argue that, without the legal mobilization pursued by these movements, neither the social right to housing[3] nor the fulfillment of the social function of private property would have been taken seriously by governments and judiciary alike. Therefore, law sits at an ambiguous place, where it can be both a sword on the hands of the powerful, and a shield to protect the dispossessed.

Brazilian Urban Development: Deregulated Expansion and Exclusion

For many decades, beginning in the 1930s, Brazil followed an exclusionary path of urban development, which had in its core “the legal recognition of property rights, more specifically, urban real property rights”.[4] This approach, embedded in “classical liberal legalism, has long made possible the definition of real property merely as a commodity, thus favouring economic exchange values to the detriment of the principle of the social function of property”.[5] A disastrous consequence of this private model of negotiating urban land is real estate speculation, which has became a serious issue all over the country and, particularly, in the metropolitan areas. It is easy to find vast parcels of land completely vacant. All in all, the housing deficit in Brazil, which reached 5,430,000 units in 2012,[6] is directly linked to the nonexistence of any regulatory mechanism of the urbanization process for more than fifty years. This condition led not only to the state’s failure in providing the population with efficient housing policies but also contributed to enhance the dynamics of a highly speculative urban land market.

Today, the design of Brazilian urban landscape portrays the deep inequalities that mark our society: while upper class neighborhoods have access to facilities, implement renovation and conservation plans and are served by a variety of public services, poor areas exhibit precarious conditions of living. In a way, one can claim that Brazilian cities display, in their streets, squares, buildings and public services, the differentiated citizenship[7] characteristic of our socio-political heritage. Formally, citizenship is universal and inclusive, but when it comes to the benefits linked to it, especially social rights, only a small parcel of population experience them fully. Therefore, urban space in Brazil mirrors the unequal distribution of wealth and the political exclusion of the lower classes. And while the city provides a material representation of these unequal conditions, it also plays an important role in reinforcing them, through the spatial segregation it structures.

Law as a Shield: The Ambivalent Legal Architecture of the 1988 Constitution

The outcome of a highly disputed drafting process, the 1988 Brazilian Constitution is an ambivalent document that amalgamates diverse aspirations, including those of the urban reform movement. For this reason, while the Constitution protects private property as a fundamental individual right, it also establishes that all private property has to fulfill a social function. In addition, the derived constituent power[8] explicitly recognized the right to housing as a social right, a victory of large-scale social mobilization. And once granted constitutional status, the right to housing, along with other social rights, requires a positive action from the state.

It is in the meeting between the failures of the state to confront the housing deficit and deliver this social right efficiently, an increase in the number of vacant land and building, and a constitutional framework that allows for an insurgent legal thesis to be developed, that the housing movement emerges in the Brazilian landscape with full force. Operating a true subversion in the dominant vocabulary, it argues that the direct action of taking back vacant land and turning it into homes cannot be framed as invasion, but rather occupation. Occupation acquires here not only a positive content, but also a dimension of legitimacy: to occupy means to enforce the law that requires every property to fulfill a social function. In this new scenario, the illegality is on the side of those who pursue real state speculation. By operating this shift in the social grammar of property and housing, the homeless families reinvent themselves as subjects of rights, and not only objects of the law. They see themselves as pursuing justice and constitutional enforcement, and by doing so speak truth to power, both public and private.

If at the beginning this seemed to be a difficult shift to take place, the movement starts now to have some victories in court. While it is still hard to dismantle completely the notion of property as the stronghold of individuality and thus fully commit to a view that grounds it on the social, a recent high court decision provides some hope. Just a few weeks ago, the Superior Court of Justice decided, in the case of probably the largest occupation in the country, that “no judicial decision is worth more than a life”. But even more important than these judicial victories are the subjective transformation that the individuals involved in the struggle undergo, as legal discourses “become meaningful through, the practical social activity of conscious legal agents”.[9]

Final Remarks

The argument I attempted to develop here is dependent upon a series of assumptions that take a step away from the scholarship mentioned earlier in this essay and critically examines how legal mobilization unfolds on the ground, in an ethnographic fashion. Indeed, in order to be able to fully apprehend the dynamic and nuanced ways in which law affects not only social movement processes but also activists themselves, it is necessary to leave to courtroom and look at the constitutive role that law plays in movement dynamics, by empowering the dispossessed and providing a novel grammar equipped with social legitimacy. It requires thus, following McCann[10], that we take an interpretive approach to examine law and its capacity to promote social change when employed by progressive social movements.

Rather than understanding the legal discourse as a limitation to political mobilization, it is important to acknowledge, first, that legal norms shape the terrain of social struggles and, second, that various legal tactics might prove a useful resource for activists to further develop their cause. In such approach, law is seen as far more than litigation and victories in courts: it is a powerful symbolic and legitimating resource – just as it may also work as a constraint – that influences larger movement processes. The case of the housing movement in Brazil, and its victories thus far, is a decisive instance of this.

—————–

[1] Boutcher, Steven A. ‘Law And Social Movements: It’s More than Just Litigation and Courts’. Mobilizing Ideas 2013. Web. 26 Oct. 2015.

[2] Idem.

[3] Article 6th of the Brazilian Federal Constitution guarantees the right to housing, as a social right, along with education, health, food, work, transportation, leisure, public safety, social security, protection to maternity and childhood, and social assistance to the impoverished.

[4] Fernandes, Edesio. 2002. Providing security of land tenure for the urban poor: the Brazilian experience. In Holding Their Ground: Secure Land Tenure for the Urban Poor in Developing Countries. Earthscan, p. 101.

[5] Idem. p. 102.

[6] According to the research conducted by João Pinheiro Foundation, available at < http://www.fjp.mg.gov.br/index.php/docman/cei/559-deficit-habitacional-2011-2012/file>.

[7] Holston, James. 2009. Insurgent citizenship: Disjunctions of democracy and modernity in Brazil. Princeton University Press.

[8] Constitutional Amendment no. 26, passed in 2000.

[9] McCann, Michael W. 1994. Rights at Work: Pay Equity Reform and the Politics of Legal Mobilization. University of Chicago Press. p. 283.

[10] Idem.

——————

Mariana Prandini Assis, is currently a PhD candidate in Politics at the New School for Social Research, in New York. She received her Bachelor of Laws and Master’s in Political Science from the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil. In her doctoral research, Mariana offers a map of women’s rights discourse production and circulation in the transnational legal sphere. Her research has been supported by various institutions, such as the Brazilian Ministry of Education (CAPES), Fulbright, and the American Association for University Women (AAUW). In her home country Brazil, Mariana is also engaged in feminist and legal activism, serving as a lawyer for social movements and grassroots organizations.

© Mariana Prandini Assis