Article in PDF (Download)

Women in the rulings of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights: Moving beyond the single story – Mariana Prandini Assis, The New School for Social Research (New York)** Reprinted by special permission of Regarding Rights

After a long battle with the mainstream of human rights discourse and institutions dating from at least the era of the League of Nations, feminists organized in a transnational movement[1] have succeeded in placing women’s issues at the centre of human rights debates.

Here I want to take a step back from celebrating these achievements and ask: if women are now part of the transnational discourse on human rights, who are these women? How do transnational human rights institutions represent them? Or, put in other words, who is the female subject of transnational legal discourse and what gendered harms are made visible in this arena?

I want to suggest that, in the case of Africa, the story we encounter is one in which women are silenced and gender is erased even when it screams to be employed as a central analytical category. If we examine the first narratives emerging from the rulings of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights[2] (ACHPR), there is no attempt to articulate in a meaningful way the specific abuses of which women are victims. Violations of women’s rights are reductively interpreted, primarily with reference to rape, and the victims are voiceless and invisible. To a great extent, the ACPHR reproduces a narrative of the victimisation of African women that predominates in the domain of international criminal law (where it occurs alongside an aggressor characterised by ‘militarised African masculinity’[3]), and which even appears in some of the Western feminist canon.[4]

Take, for example, the Communications 54/91-61/91-96/93-98/93-164/97-196/97-210/98, brought to the Commission by the Malawi African Association, Amnesty International, and other organizations, against the state of Mauritania. The allegations included state repression of political dissent and denial of justice to those taken to trial. State violence also reached villagers in the South of the country, where security forces had occupied and confiscated land and livestock, forcing the inhabitants to flee to Senegal. It is in the description of the scenes of horror taking place as villages were taken over that women appear, for the first time, as victims of human rights violations: “Whenever the villagers protested, they were beaten and forced to flee to Senegal or simply killed. Many villagers were arrested and tortured. […] As for the women, they were simply raped.” (emphasis mine)

A similar pattern appears in the communication presented by the Democratic Republic of Congo against the Republics of Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda.[5] The allegations concerned “grave and massive violations of human and people’s rights” by rebels from the three accused countries against civilians living in the Congolese provinces. As in the case of Mauritania, rape functions on the one hand to demonstrate the seriousness of the human rights violations that occurred but on the other hand does not warrant any deep or sustained consideration. The particularity of the violence suffered by individual women disappears from view as it becomes a mere rhetorical device to characterize the state of “gross human rights violations”.

What we draw from these cases, and others considered by the ACHPR that I have examined,[6] is a single story, the dangers of which are highlighted by Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie[7]: this single story creates (and I would add, sometimes only reproduces) stereotypes. The single story, embedded in relationships of power, becomes the only story and comes to define in a unified and reductive way the diverse experiences of the individuals whose story is told. By producing a single story of the female victim of human rights violations in different contexts, the ACHPR not only conceals the variety of women’s experiences but also the different effects of gender-based violence on both women and men. It essentialises them into monolithic groups of victims and perpetrators. Moreover, it reduces the harms suffered by women to the sole experience of sexual violence, producing a female subject who is only recognised by reference to her sexual identity and her vulnerability to being raped. Finally, by encapsulating the experience of sexual violence within the female subject, it also overshadows the various ways in which men are also victims of this injury.

To defeat the dangers of the single story, different narratives must be allowed to emerge, and most importantly, the subjects of these stories need to be able to create the narratives themselves. Another case examined by the ACHPR helps to illustrate this point, offering a glimpse of how the single story rape narrative can be disrupted by the incorporation of women’s voices. Systematic violations of the human rights of indigenous tribes in the Darfur region were brought before the Commission in two different cases against the state of Sudan.[8] Massive and on-going human rights violations were alleged that included extra-judicial executions, torture, arbitrary arrests, poisoning of wells, forced evictions and displacement, destruction of property, detentions and rape of women and girls. Given the severe character of the conflict and its dreadful consequences, the Commission sent a special mission to report on the events taking place.

While the framing of the case by the Commission did not differ much from those discussed above, the first hand account provided by refugee women to the Commission functioned as a disruption of the victim narrative. For these women, rape was certainly an important part of the brutality they suffered, but also important was their inability to access water and the impossibility of sending their children to school. The permanent sense of insecurity they felt, moreover, was founded not solely on the threat of sexual violence but also on other forms of intimidation including their fear of losing their homes. The refugees’ accounts point to economic and social dimensions of life that are equally important for women but which are made invisible in the ‘all the women were raped’ narrative. The inclusion of women’s voices and perspectives thus generated a disturbing contrast between the female subject constructed by the Commission and the one who thinks and speaks for herself.

While the African Commission has the space and the legal instruments to go beyond such a reductive narrative (which not only silences women but also curtails their agency, including as political beings and even as perpetrators[9]), in the cases mentioned above it did not do so. On the contrary, the Commission remained trapped in the ‘women as victim of rape’ discourse, which not only diminishes the transformative potential that human rights may have, but also contributes to the reproduction of old gender stereotypes present in colonial discourse. Here, women’s sexual security seems to function as a benchmark of civilization in a continent whose history is reduced to a continuum of war.

This does not mean, however, that we should simply abandon the language of human rights. Rather, we need to recognise that human rights law is a site of struggle: it is constituted through a series of ideas, practices and engagements which have material consequences for individuals’ lives. Our role then is to subject it to a process of critical interrogation, highlighting internal inconsistencies, paradoxes, limitations, and silences. In other words, it is necessary to create the space for counter-stories to emerge so they can change the course of our grand human rights narratives.

————–

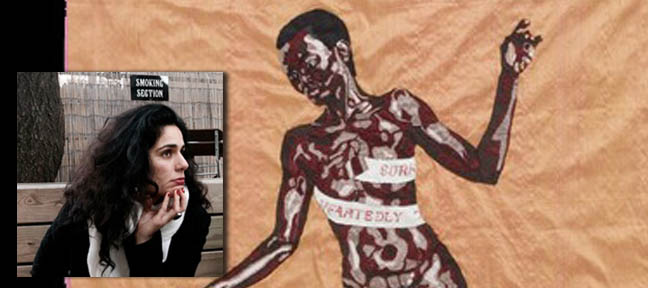

*Billie Zangewa is part of a group of contemporary African artists who aim to reclaim African women’s agency and control over their bodies without losing sight of the significance of colonial history and current economic and social structures.

**The content of this post is based on part of my doctoral research, which has been funded by CAPES, Fulbright and the American Association of University Women, to all of which I express my gratitude.

[1] Following important achievements in the previous decades, such as the adoption of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) by the UN General Assembly in 1979, and the 1985 World Conference on Women in Nairobi; feminist advocates gathered on different occasions in 1992 and 1993 to shape the draft Declaration and Programme of Action on Human Rights approved at the Vienna World Conference in 1993. In 1994, the Inter-American Convention on the Elimination of Violence Against Women was adopted and in 1995, the fourth World Conference on Women was held in Beijing.

[2] The African Commission on Human and People’s Rights was established in 1987 with the mission of protecting and promoting human and peoples’ rights as well as interpreting the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

[3] Chiseche Salome Mibenge, Sex and International Tribunals: The Erasure of Gender from the War Narrative (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 7.

[4] See, for a critique of this literature, Karen Engle, “Female Subjects of Public International Law: Human Rights and the Exotic Other Female,” New England Law Review 26 (1992 1991): 1509–26.

[5] Communication 227/99: Democratic Republic of Congo Vs. Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda. Decided in May 2003.

[6] See, for example, Communication 249/02: Institute for Human Rights and Development in Africa (on Behalf of Sierra Leonean refugees in Guinea) Vs. Guinea.

[7] Her talk can be seen here: http://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en.

[8] Communications 279/03-296/05: Sudan Human Rights Organisation & Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) Vs. Sudan.

[9] Karen Engle, “Feminism and Its (Dis)contents: Criminalizing Wartime Rape in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” The American Journal of International Law 99, no. 4 (2005): 778–816.

—————

Mariana Prandini Assis, is currently a PhD candidate in Politics at the New School for Social Research, in New York. She received her Bachelor of Laws and Master’s in Political Science from the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil. In her doctoral research, Mariana offers a map of women’s rights discourse production and circulation in the transnational legal sphere. Her research has been supported by various institutions, such as the Brazilian Ministry of Education (CAPES), Fulbright, and the American Association for University Women (AAUW). In her home country Brazil, Mariana is also engaged in feminist and legal activism, serving as a lawyer for social movements and grassroots organizations.