Article in PDF (Download)

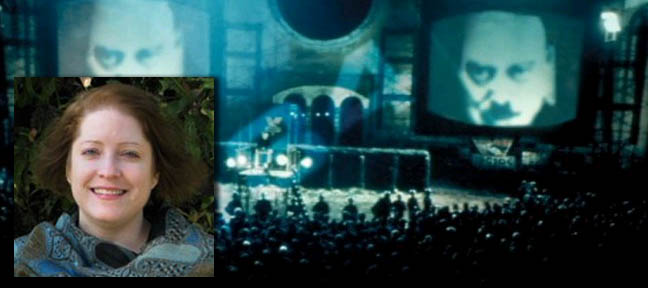

Fighting Government Surveillance with Industry Transparency Reports by Dr Natasha Tusikov, Baldy Centre for Law and Social Policy, University of Buffalo, State University of New York. Reprinted by special permission of Regarding Rights

Classified files leaked by Edward Snowden reveal that the Internet surveillance programs operated by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and its allies are heavily reliant upon data drawn from U.S.-based Internet firms like Google, Microsoft, Twitter, Apple and Facebook. Reaction to the Snowden files continues to reverberate worldwide with anger from political leaders and the public directed towards the NSA and companies that facilitate its surveillance programs. As part of their response to the public outcry and anger from their customers, a growing number of Internet firms are producing and publishing “transparency reports.” In this context, transparency is a principle that enables the general public to gain information about the operations, structure and activities of a given entity, such as a company or government.[1]

Industry transparency reports are records published by companies that disclose certain data or information about the operation of and activities undertaken by a company. Companies may institute transparency reports for a variety of reasons, such as to demonstrate compliance with state laws, industry rules or non-governmental certification schemes. Some transparency mechanisms may be mandatory, such as food labeling requirements. Other disclosures are voluntary (for example, to repair or strengthen corporate reputations damaged by scandal). Google, Twitter and other technology companies voluntarily produce Internet transparency reports. These reports detail how and under what circumstances they divulge or remove information from their platforms, and track those activities over time.

There are two types of industry-produced Internet transparency reports. Most commonly, these reports disclose how Internet firms divulge their users’ data to law enforcement agencies around the world in response to warrants or court orders. Internet firms also disclose national security-related requests they receive, particularly from the U.S. government. Additionally, some Internet firms also track requests from corporations for the removal of content, especially in connection with copyright-infringing material like unauthorised downloads of music, movie and software. Internet transparency reports are, in part, intended to reveal to the public the nature and scale of government surveillance and regulation on the Internet undertaken by Internet firms.

Google was the first Internet firm to institute a transparency report in 2010. The goal of Google’s report is to inform people about government requests for user data and content removal in the hope that “greater transparency will lead to less censorship.”[2] Following the negative publicity of the NSA’s surveillance practices as revealed in the Snowden files, multiple U.S.-based Internet and telecommunications firms adopted transparency reports. Yahoo, Microsoft, Apple, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Tumblr, Pintrest and Dropbox each publish transparency reports. A number of telecommunications firms also publish transparency reports, including AT&T, Verizon, Telus, Telstra, and Vodafone, along with Comcast, Rogers, and Time Warner.

Internet and telecommunications firms are legally constrained in the amount and type of information they can publish in relation to national security-related requests. In January 2014, Internet firms reached a deal with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) in exchange for dropping their lawsuits related to publishing restrictions.[3] Twitter was the only firm to refuse the deal and, in October 2014, it filed a lawsuit in U.S. federal court declaring restrictions on publication unconstitutional. Under the deal, companies can only publish court orders received under the U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act,[4] which authorizes much of the NSA’s surveillance practice, in increments of 250 or 1,000. They must also institute a six-month time lag on the publication of orders they have received. These restrictions significantly limit the amount of detail companies can release. Yahoo, for example, reports receiving 0-999 requests from FISA for the disclosure of content in relation to 30,000 to 30,999 user accounts between January 1 and June 30, 2013.

Only two Internet firms — Google and Twitter — disclose the requests they receive from rights holders, which are often large corporations like Sony Music, for the removal of copyright-infringing content from their platforms.[5] These companies record the number of requests they receive for the removal of content and the percentage of content removed in those requests. They also list the entities requesting the removal of infringing content, such as Walt Disney Company. Usefully, Google also records requests where it has taken no action in response to complaints of copyright infringement. Google receives the bulk of complaints from rights holders as the largest search engine globally. In 2013, Google removed 200 million search results that linked to copyright-infringing content.[6] As of August 2014, Google processes approximately one million complaints daily.[7]

For Internet companies transparency reports are a useful vehicle to begin to inform the public of the nature and scope of Internet regulation by governments and rights holders, particularly large corporate actors. Industry transparency reports can be effective public relations tools if they can convince users that the firms are trustworthy guardians of their data. Companies can use the voluntary disclosure of information not only to repair corporate reputations but also to generate ongoing goodwill among their users and business partners.[8] Yahoo’s CEO Marissa Mayer observes that the Snowden revelations hurt Yahoo and the company wants “to be able to rebuild trust with our users.”[9] Firms have a pragmatic motive for maintaining users’ trust and loyalty. “People won’t use technology they don’t trust,” explains Microsoft’s general counsel Brad Smith.[10] Transparency reports also enable firms to distinguish their commercial activities from controversial state surveillance programs and let them critique surveillance practices, particularly by the U.S. government. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO, argues that greater transparency by governments is “the only way to protect everyone’s civil liberties and create the safe and free society we all want over the long term.”

Internet firms are financially and ideologically motivated to disclose national security-related requests given the anger of their customers and business clients over the NSA’s surveillance. However, the firms have fewer incentives to track the enforcement efforts they undertake on behalf of rights holders. In contrast to the NSA scandal, there was no equivalent public pressure on companies to divulge the regulatory efforts they undertake for rights holders like Nike, Sony or Disney. Companies can be reluctant to adopt policies of information disclosure, particularly in the absence of other companies doing the same; they may perceive that the release of information could undercut their competitive position in the marketplace.[11]

Overall, Internet firms’ voluntary disclosure of information is a relatively weak form of transparency. The reports provide only partial accounts of the firms’ regulatory activities, as they are not permitted to publish detailed information about government requests for data, particularly in relation to national security. Jeremy Kessel, Twitter’s manager of global legal policy, argues that restricting disclosures to “an overly broad range seriously undermines the objective of transparency.”[12] Further, most Internet firms do not track their enforcement efforts on behalf of rights holders and thus under-report rapidly growing corporate regulatory efforts. Internet firms’ business models are typically built upon collecting and data-mining information from their users. These firms thus have strong financial incentives to expand their own surveillance capacities while, at the same time, strategically separating their efforts from controversial state surveillance programs.

Discussions of transparency inevitably raise two important questions: transparency for whom and for what purposes? In relation to Internet surveillance and regulation, transparency is intended to raise public awareness of government and, to a lesser extent, corporate governance practices. Transparency in itself, however, is not a catalyst for change.[13] Nevertheless, corporate information disclosure can be a valuable tool to strengthen accountability and improve democratic oversight. Kevin Bankston, Senior Counsel and Director of Free Expression for the digital advocacy group Centre for Democracy and Technology, argues that “we cannot have a meaningful debate about the scope of the government’s surveillance authority until we have an informed public.” Internet transparency reports are a necessary component of a larger project to shine a much-needed light on state and corporate regulatory activities on the Internet.

With greater public knowledge of corporate-governance regulatory practices, we can further engage in debates over the changing nature of regulation on the Internet – by governments and corporations – and explore implications for digital rights, particularly privacy. In an era of mass surveillance by both states and corporations, we must fully debate fundamental questions related to how we access and use the Internet. Who owns our data, what rights do we have to control how states and corporations use our digital footprints, and what are (and should be) their roles and responsibilities regarding data disclosure and protection?

[1] Etzioni, Amitai. 2010. “Is Transparency the Best Disinfectant?” The Journal of Political Philosophy 18(4): 389-404; Heald, David. (2006) “Varieties of transparency.” Transparency: The Key to Better Governance? eds. Christopher Hood and David Heald, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 23–45.

[2] Drummond, David. 2010. “Greater transparency around government requests.” Google Official Blog. April 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2013 http://googleblog.blogspot.com.au/2010/04/greater-transparency-around-government.html

[3] Department of Justice. 2014. “Letter to General Counsels of Internet Firms.” Office of the Deputy Attorney General, Washington, D.C. 27 January 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014 http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/366201412716018407143.pdf

[4] The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, introduced in 1978 and repeatedly amended since 2001, allows the NSA to work with companies to copy, collect and analyse Internet and phone traffic (including emails and voice-over-Internet calls). See: https://it.ojp.gov/default.aspx?area=privacy&page=1286.

[5] Internet companies are required by law in most jurisdictions around the world to remove copyright-infringing content. Companies operating in the United States, for example, must comply with the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DCMA). Under the DMCA and similar legislation, companies must remove content upon receiving legitimate complaints from the rights holders that own the copyright in question. There is no requirement in the DMCA for companies to disclose their enforcement efforts. See: Digital Millennium Copyright Act (Pub. L. 105-304, October 28, 1998), 105th Congress, 1997–1998, Retrieved November 13, 2012(https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/105/hr2281).

[6] Ernesto. 2013. “Google Deleted 200 Million ‘Pirate’ Search Results in 2013.” TorrentFreak12 November 2013, Retrieved 14 January 2014

https://torrentfreak.com/google-deleted-200-million-pirate-search-results-in-2013-131112/

[7] Ernesto. 2014. “Google Asked to Remove 1 Million Pirate Links Per Day.” TorrentFreak 20 August 2014, Retrieved 13 September 2014

http://torrentfreak.com/google-asked-to-remove-1-million-pirate-links-per-day-140820/

[8] Etzioni, Amitai. 2010. “Is Transparency the Best Disinfectant?” The Journal of Political Philosophy 18(4): 389-404.

[9] Petroff, Alanna. 2014. “Marissa Mayer calls for more NSA transparency.” Money CNN. 22 January 2014, Retrieved 11 February 2014

http://money.cnn.com/2014/01/22/news/companies/mayer-tech-nsa/

[10] Smith, Brad. 2014. “Unfinished business on government surveillance reform.”Microsoft on the Issues – blog 4 June 2014, Retrieved 23 August 2014 http://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2014/06/04/unfinished-business-on-government-surveillance-reform/

[11] Haufler, Virginia. 2010. “Disclosure as Governance: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and Resource Management in the Developing World.” Global Environmental Politics 10(3): 53-73.

[12] Kessel, Jeremy. 2014. “Fighting for more #transparency.” Twitter Blog 6 February 2014, Retrieved 22 August 2014 https://blog.twitter.com/2014/fighting-for-more-transparency

[13] Ibid 11.

—————————

Natasha Tusikov is a research fellow at the Baldy Centre for Law and Social Policy at the State University of New York, Buffalo. A dual Canadian-Australian citizen, she received her Ph.D. in Sociology from the Regulatory Institutions Network at the Australian National University. Her research explores private (particularly corporate) regulation on the Internet and the interplay between law and technology. Prior to her work in academia, she was a researcher and intelligence analyst for federal law enforcement agencies in Canada.