Article in PDF (Download)

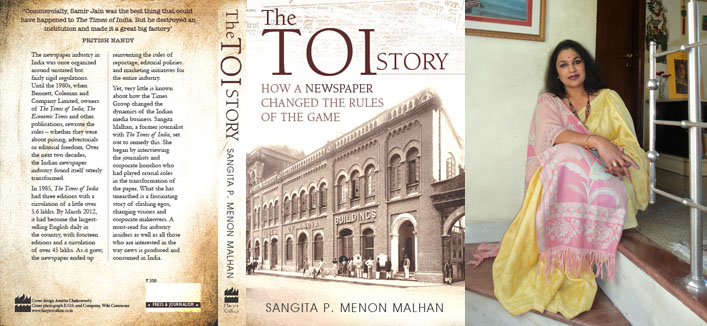

Sangita P. Menon Malhan has written this article on her book – The TOI Story: How a Newspaper Changed the Rules of the Game. Published by HarperCollins India – This book has won the Gold Medal for the best book on media industry in Asia – LINK

Every thing that becomes great… becomes greater, after being less.’’ Plato, quoting Socrates, in his `Phaedo’.

It took 12 years to complete “The TOI Story”, from concept to print. During one of the few hundred interviews for the book, an industry top notch who had played a leading role at the Times of India, told me: “Quite simply, the Indian media story can be divided into two parts – pre Samir Jain, and post Samir Jain”. And then, he proceeded to detail out the differences between the two.

He may have overdone it a bit. Nevertheless, during the course of this journey, I realised that the current state of the Indian media – mainstream “national” media at any rate – is influenced in large measure by what Samir Jain and The Times of India tried out over two decades ago.

There are strong views on whether we are better off today with the sort of media we have given ourselves. I have refrained from making any judgements, preferring instead to let a lot of relevant people on either side of the debate voice their views even as I unravelled and documented this most fascinating story.

I joined The Times of India in New Delhi as a city correspondent in 1994. By 2001, I was writing on aviation and hospitality. It was at this time that something happened to me.

One day, I was drawing up a list of potential interviewees to profile for the business pages. I had interviewed Richard Branson of Virgin Atlantic and Naresh Goyal of Jet Airways among others. When it came to the media as a domain, I realized that the greatest growth story in the media in India had happened right where I was; at Times House.

I was curious about how my newspaper had become such a success; why it carried the content that it did; how The TOI became the largest-selling English daily newspaper in the country, and subsequently, in the world. I couldn’t have done justice to the project while working at the newspaper. Besides, I wanted the freedom and the time to pursue the subject.

I moved out of The Times in April 2001 to begin my research; without a contract from a publisher for the book; without any support (or obstruction, for that matter) from The TOI; and without a grandiose plan. I did draw up a list of editors and heads of marketing and advertising I was going to interview. I intended to see the story through their eyes, and take in their narrative to get the big picture. People were initially incredulous, even amused by the initiative. But many of them overcame this and shared their stories with me.

The core of Samir Jain’s thought has been that his publications must offer superior value to the advertiser. Every aspect of his business has to be aligned to deliver that. This is the touchstone for decisions and initiatives at the Group. The TOI group, self admittedly, is all about “aggregating audiences for the advertiser”.

Pushed to the limit, this means that if the newspaper is forced to choose between an erudite editor’s expounding on larger national issues and upper middle class professionals worried about water shortage and unsafe neighbourhoods, then the latter would get preference in the columns of the newspaper.

If the consuming classes find a certain style of language stiff and uncomfortable, it will be replaced with something lively. If these targeted classes did not have time for long reports, the stories would be crisper. If lifestyle, celebrity, education, travel and fashion were their new priorities, separate supplements would be spun out to serve them, and to serve the advertiser.

Samir Jain went about making these changes systematically. He brought in concepts hitherto unknown to this domain. Even as rivals looked on, he re-jigged content; put the spotlight on local issues; created supplements with a view to tapping the advertising segment and also to cater to a niche client base; his publications became colourful and snazzy; highbrow pontificating gave way to simpler, clearer, wittier language. He backed this with clever marketing moves. He combined the advantages of all his main publications and offered them as a collective to the advertiser, thereby changing that pattern once and for all. He hiked the rates for space in certain publications such as The TOI, Bombay where he is the dominant leader, and then sweetened that by offering space in lightweight editions across north India for a nominal, additional fee.

To attract advertisers in Delhi, where he was a distant second to The Hindustan Times, he spoke of the `value’ that his publications delivered instead of focusing merely on circulation.

People described those changes and the surrounding controversies with great emotion. They told me how Jain shut down many publications of the group, including those which had been launched by his grandparents and were respected among the intelligentsia. They said he wanted to sharpen his focus; they explained how the decision was met with severe shock and indignation, but how he still went ahead.

This was fine to the extent that no one could grudge a businessman trying to become more relevant for his audience. Except that the other side of the debate was that this is not a soap business. This is an “institution”. The media has to rise above commerce, as it were, since it had a larger role. The Times of India, with its long tradition and leadership position, was obliged to play that role.

As one of the stalwart editors, Girilal Jain, famously observed (and is quoted in The TOI Story): “I do not regard The Times of India as a family owned or company owned newspaper. I regard it as a national institution. …If it were to be run as a company-owned concern, I won’t fit in”. And then, he went on to add: “For me, it (being editor) is national service with a certain amount of payment”.

But Samir Jain was not interested in that “larger role”. He wanted to do what his advertisers wanted, and by extension, that which would touch the sort of readers whom the advertisers targeted. What added colour and interest to these battles was the personality of Samir Jain himself: reclusive, spiritual, focussed, and with an almost uncanny knack of anticipating – and shaping – the demands of his customer.

By and by, the media world began to take Samir Jain seriously. It criticized him, but also watched him closely, and followed what he did. Today, practically every leading newspaper in the country brings out its own supplements; launches localized editions; brings out its own version of the price matrix; rakes in the glamour, the celebrity. It condescends to conquer.

The context in which these changes took place was also conducive. India was beginning to change. Consumerism was no more a dirty word. It was all right to want to make money. Entrepreneurship was emerging. The stranglehold of the government would loosen up. Economic reforms were unleashed with a vengeance. And, Samir Jain had been able to read the message in the wind, and take that leap of faith. In that sense, he becomes the pioneer; also the `perpetrator’ of change.

There are accusations against The Times of India. It `dumbed-down’ journalism. It guillotined the great power of the editorial cadre. It brought in advertorials and entertainment into the newspaper. Some of the columns in its supplements are up for sale. Small newspapers have died. He has `commercialized’ news in India. The Times of India, admittedly, is in the business of advertising, entertainment, or “infotainment”, not news.

Indeed change has been coerced on the print medium in the country. Benefits have accrued to the consumer and the advertiser. Pulp and trivia have found a clientele. It is a high-stakes venture. Monetary gains drive the media enterprise like any other. While there are many more players, they often end up as clones of each other.

There has been growth. Readership and circulation are both growing in this country while newspapers across the world are folding up or being consumed by their peers in the digital space.

Undoubtedly, all this has had a strong bearing on shaping contemporary media in India. “Aggregating audiences for the advertiser” has been replaced with the supremacy of the TRP, with much greater vigour and clarity.

The main concern with this subservience to the news consumer – and by extension, the advertiser – is whether the media is now left pandering to the least common denominator. In its focus on news that you “want to know”, has it completely lost sight of news that you “ought to know”? Is mainstream national media now circumscribed by the narrow and immediate concerns of the middle class, and is unable to take up more in-depth and long term issues?

I refrain from making any judgements here.

The sense I have got from the TOI group is they recognised at some point that they had taken relevance too far and perhaps trivialised issues. Besides reversing some of that, they have also tried to discharge the “national institution” role through multiple social campaigns. It seems to them that young people want to make a difference by participating and doing, more than by analyzing and discussing issues in newspaper columns.

What does one expect from the media and from the leader of the pack? With its sizeable resources and reach, we expect more research and analysis; more intervention in areas that matter; and in cases where columns are for sale, perhaps a fuller disclosure!

Of course the environment is changing rapidly. Content is now being “aggregated” in cyber space, tempting one to question the relevance of the media as it exists. That may be a little premature. Knowing The Times of India, one can be certain that there will be profound changes to adapt and win, as the world around us transforms.

I’m glad the opportunity to capture the most defining upheaval in the medium came to me. And, no matter what more happens to print in India, the story of the mid 1980s to the `90s will always be when it all began!

———————————

Sangita was born to a Sikh mother and a Malayali father on 28 November 1967 in Kerala. She grew up in Mumbai, Madurai and Jaipur. Media has played a central role in her life. Her father was a journalist with the news agency – the United News of India for nearly 35 years. Newspapers and books were readily available in her home while she was growing up; reading was facilitated and encouraged.

Sangita was a journalist for ten years, including six-and-a-half with The Times of India. She also worked for the Delhi Mid Day and The Statesman. Prior to being a journalist, she was national Gliding champion, a gold medalist; a cadet in the National Cadet Corps. She subsequently acquired a Private Pilot’s Licence. She studied Political Science and History in college.

Sangita has a natural flair for languages. In the 12 years that she has worked on The TOI Story, she acquired an Advanced Diploma in French; she teaches and translates the language. She has published a collection of Urdu poetry (Nusrat-e-Gham – The Triumph of Grief. 2012). She learnt Bengali in 2012 so that she could read Rabindranath Tagore in the original; and, picked up elementary Spanish to be able to use the language in Spain during a visit in June 2013.

Her collection of short stories, Rastapherian’s Tales, was published by the Writers Workshop in 2010. She has an in-built attraction to machines, in particular, to bikes, and was the first female patron in the city to test ride a Harley Davidson when it arrived in Delhi. The pursuit of music and Art are also an integral part of her creative life. She unwinds by reading poetry; and by visiting Art exhibits. Leonardo da Vinci, Claude Monet, Vincent Van Gogh, Botticelli, Picasso and Salvador Dali are among her favourites.

She is married to Captain Tejinder Singh Malhan, a senior commercial pilot and Examiner with Air India whom she met during her flying days. Their son, Avii, 16, is an avid footballer and heavy metal guitarist; passionate about satire and about dark humour.