Article in PDF (Download)

Noel Monahan, Celebrated Irish Poet, speaks on a United Ireland to Mark Ulyseas

Are Celts the indigenous people of Ireland?

In so far as the Celts have been in Ireland since the Iron Age, I think it is reasonable to say they are an indigenous people here. But the Celts were not the first people. Leabhair Gabhála Éireann, The Book of Invasions lists a number of peoples predating the arrival of the Celts. They mention The Firbolg and the Tuatha Dé Danann, people of the goddess Danu. This Leabhair Gabhála is a loose collection of stories, legends and myths. The text has come down to us in a number of medieval manuscripts compiled in the 11th century and not the reliable primary sources that true historians like to work with. As we all know today, the Celts occupied central Europe spreading over to the Balkans. Now the Celtic group we are interested in here is the branch of the race which spoke the Goidelic tongue, the language we now call Gaeilge, present day Irish. I think it is fair to say the core of Irish heritage is Celtic. Our very home addresses, townlands are Celtic in origin.

Many poets today are interested in the Dinnseanchas, place-name lore. For instance I live in Stragelliffe, Strath An Ghála translates as Meadow of Storm. Two of my plays: Deirdre of Sorrows and the Children of Lir are ancient Celtic stories and only last year I told in modern day Irish the famous story of the mad King Sweeney who was banished to the trees by St. Ronan at the time of the coming of Christianity to Ireland. Celtic archaeological sites pepper our landscape. In the 1980s an Iron Age Road was discovered in a bog in my home county of Longford. It is true to say the Celts still engage us and provoke our curiosity. In a post- modern Ireland of today, the Anglo-Irish Revival of the late 19th and early 20th century hasn’t quite vanished.

In the mid-5th. century CE St. Patrick arrived on the island bringing Christianity. What was the prevailing “religion” at that time and how did Christianity become The “ main religion”?

Very little is known of the specific paganism that existed then in Ireland. It is generally accepted that there was a class of druids, a priestly society similar to that of the Indo-European tradition. Certainly, ancient history seems to paint a picture of man’s fears and vulnerability and the constant reliance on nature to provide food. There was an urgent need to offer sacrifice to placate the gods.

The Gaelic word draíocht, meaning magic, has the same root form as druid, so we can assume the druids were associated with magic of some kind. There are many gods mentioned in Irish Celtic legends. The more prominent being: Ogma, Brigid, Lugh, Nuada and the fearsome Crom Cruach. Crom Cruach had twelve sub gods and it is generally accepted that he received human sacrifice. His place of veneration was Magh Slecht in Co. Cavan.

St. Patrick arrived in Ireland circa 432 to a backdrop of paganism as I have already indicated. St. Patrick’s arrival not only announced the message of Christ but also initiated an education system that had not being experienced before. Christianity was like a new technology. It liberated us into a new way of thinking, we moved away from pagan ways and human sacrifice. It led to a new enlightenment in Ireland. Monasteries were set up and became centres of education. The Irish were introduced to a new language. Latin was taught in the monastery schools and this led to a golden age we later shared with Europe. I am not saying the change-over happened suddenly. I am sure it was gradual and in some cases the old pagan ways persisted well into Christian age. The legend of King Sweeney and St. Ronan, Buile Suibhne/ Mad Sweeney, is one example of the opposition to Christianity. This legend is well documented in Seamus Heaney’s Sweeney Astray, 1983 and I have a modern Irish version of the same, Suibhne Faoi Bhodhráin Ghealaí/ Sweeney Under A Full Moon, due for publication in 2014.

In the last 400 years Ireland has faced unprecedented invasions, witnessed bloody battles and been the victim of foreign [ British/English?] religious-political machinations that has resulted in the present day divide of the country, as well as, between Catholics and Protestants. What is the historical background that has lead to Ireland being partitioned into Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland? And has religion played a pivotal role in this division?

The Nine Years War 1594-1603 resulted in the military defeat of the Irish chieftains of Ulster. This defeat brought about what is known in Irish history as The Flight of The Earls. Irish chieftains like O’Neill and O’Donnell headed to the continent to seek military help from Catholic Europe. Their land was confiscated and given to English and Scottish planters/settlers and thus began the Ulster Plantation and the start of the Northern Ireland Troubles. It is important to state that the Irish chieftains themselves operated a landlord/tenant system. However, the fact that the new landowners were English and Scottish didn’t help and the policy of colonisation had one intention and that was the Anglicisation of Ulster .It was a Protestant colonisation. English planters were mainly Church of England and Scottish planters mainly Presbyterian. So from the very beginning religious differences played a major role in the conflict. It is important to address your your question on bloody battles. The 1641 rebellion was a rising of Irish against English rule in Ulster. This was a fierce and bloody event often glossed over in Irish history. One of the main reasons for Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland was to avenge the atrocities of the 1641. Cromwell’s slaughter of the Irish was a bloody affair. It is important to view this conflict at this point in history with that of the religious wars in Europe. Religious differences did mark out the divides but there were always the economic and political differences.

Has the IRA, in all its avatars, been solely responsible for the major part of Ireland becoming a Republic? And can another large scale program of violence against Britain bring about a united Ireland?

“Avatars” is a very important word here and one must know the IRA had many incarnations. The 1798 Rebellion in Ireland was first airing of republicanism after the French Revolution. It was a military failure with risings North and South of Ireland. It is important to note here that one of the leaders, Henry Joy McCracken, was a Belfast Presbyterian. So republicanism was not a simple war of Catholic Ireland against British Protestantism at that point.. The Presbyterians both North and South fought on the same side as Catholics in the 1798 Rebellion. As a result of the 1798 rebellion the Union of Great Britain and Ireland was set up in 1800. This is a key towards a long range understanding the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Now Irish politicians were sitting in Westminster, London.

Between 1800 and 1921 Irish political energy was either military or constitutional. Popular constitutional movements sought the Repeal of the Union and a form of Home Rule by debating in the chamber. The roots of the IRA in its many avatars featured in many military campaigns such as Young Irelanders in 1848 and IRB ( Irish Republican Brotherhood) in the 1860s. Continuous military failure lead to the popularity of the Home Rule Movement of which Charles Stewart Parnell was main leader. The famous Home Rule bills came before Westminster, the first in 1886 and 2nd.

In 1893 and although both were defeated it looked as if the 3rd. Home Rule Bill might be passed in 1912. The Protestants of Ulster favoured Unionism and were totally opposed to Home Rule and this is the beginning of a divided Ireland of North and South. Ulster Unionism used slogans such as “Ulster Will Fight and Ulster Will Be Right” “ Home Rule Will Be Rome Rule” The Orange Order rallied the troops, the Solemn League and Covenant was signed by Ulster Unionists, pledging loyalty to the crown of England and Ulster Unionism. World War 1 intervened, England’s difficulty was perceived as Irish Republicanism’s opportunity and the famous Easter Rising happened in 1916. This was a city revolution confined to Dublin. It was a rising of poets, intellectuals, trade unionists and republicans. It lasted a week and then you had unconditional surrender and the executions of the leaders of the rising.

Most historians agree that the manner in which the executions were carried out led to a change of heart by the collective Irish in the South of Ireland and the results of the 1918 General Election led to a landslide victory for SINN FÉIN (Ourselves Alone) the new political party with its unofficial army of the IRA.

A war weary England (post WW1) offered negotiating opportunities to the Irish after two years of gorilla-warfare in the War of Independence and there followed the famous Irish treaty and partition, with Ulster still part of the British Empire. To answer your question, yes the IRA in all its avatars was responsible then in achieving the establishment of The Irish Free State.

The second part of your question takes us to present day Ireland. Ireland is a totally different country today. Politics in the South of Ireland has changed. The concept of nationalism has changed. I feel we no longer perceive nationalism in military terms. We are living in post Celtic Tiger Ireland. Our collective body of people belong to a post- modern secular Ireland. One should consider the diaspora and how nationalism lives abroad. The population of Ireland is about four million but beyond the geography of this island 93 million claim to be of Irish descent .

We have to take into account a broader picture.The role of the Catholic church has diminished in our lives. The Queen of England visited Ireland, attended a ceremony in the Garden of Remembrance, spoke a few words in Irish at a dinner in Dublin Castle and her visit was very popular with media and all concerned. What is a United Ireland? A unity of space whereby all the island of Ireland is under the same government. I favour more a unity and understanding of our differences. Human rights for all people is more important than the nationalism of the past. Nationalism like everything else has to evolve and move on. For me the nationalism felt when England played Ireland in rugby in Croke Park is a greater indicator of nationalism for the future. I do not agree with any program of violence to achieve a so called united Ireland. If it happens in the future let it evolve peacefully.

Are there people to people contact (Trade, Arts, Education, et al ) between the Northern and Free Ireland? If so, can you give us some examples?

Much has been done in the arts and education to promote a proper understanding of the cultural differences that exist between the North and South. The Arts Council of Northern Ireland have had joint ventures with the Arts Council of the South to promote peace and understanding.

The National Rugby team is chosen from the thirty two counties (The whole of Ireland). Gaelic football and the G.A.A. (Gaelic Athletic Association) is open to an all Ireland contest every year and the six counties participate. The Peace 111 movement promotes peace and understanding especially in border counties. Politicians both North and South, together with British and American initiatives have worked tirelessly over the years to promote peace in Ireland.

As a celebrated Irish Poet what role do you think the Irish poets, writers and other artists of the isle can play to bring about the unification of Ireland? And do you think this (unification) will happen in your life time?

I feel poets and artists have played and continue to play a major role in the peace movements. Take for example The William Carleton Summer School. This school was set up in Clogher, Co. Tyrone in 1982 to commemorate the life and works of the writer William Carleton. This summer school takes place every August and writers, academics and scholars deliver papers on the works of Carleton. William Carleton (1794- 1869) was born a Catholic but as he was about to launch on his literary career he changed religions and became protestant. A study of his many novels illustrates the difficulties of the Irish Catholics in Northern Ireland in the 18th. century and the pain endured as they gradually moved from speaking Irish to the English tongue. Much of Carleton’s work is written in a special type of English known as Hiberno-English, where the Irish idiom and syntax of words is like direct translation from the Irish language. This is especially true of his famous work: Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry. I have had the pleasure of reading at this great summer school over the years.

In July of this year I read at the John Hewitt Summer School in Armagh. John Hewitt was an Ulster poet of planter stock. His life and works take us through his search for identity in protestant Ulster. His writing has a strong sense of the Ulster landscape and his MA thesis was based on research of the Ulster Weavers Poets of Down and Antrim. Being involved as a poet and reading at such summer schools helps to further our understanding of the complex cultural situation that is Ulster. Also this summer I edited an Anthology: Writing Across Borders. The book featured the work of writers from Monaghan, Barnavan Writers group from Cookstown and Lough Neagh Writers’ group from Craigavon. The writing dealt with the inner thoughts of a people who came through the Troubles. Writing Across Borders was brought about by Monaghan Community Forum’s “Hands Together 2”Peace 111Project. This project used the tools of Art and Heritage to bring communities and individuals from different religious and political backgrounds together. The Writers In School Scheme, under the umbrella of Poetry Ireland have organised readings and workshops of poetry both North and South of the border.

Getting back to answering your question, I feel such summer schools and literary workshops and publications help to educate all of us. At this point in time, we are not focusing on a political unification. We are happy to bring about a deep understanding of our cultural differences and the great need for respect and understanding of each other. If we have peace and understanding we have a real unification. It doesn’t have to be political. Such a unification cannot be forced. It may and can evolve.

Could you share with us a glimpse of your life and works?

I was born in Granard, County Longford, Ireland on Christmas Day, 1948 and that might account for my many poems on the subject of winter celebrations. I grew up on a farm there and I feel the fields and the landscape had a strong influence on my later work as a poet. Granard was a market town then with a population of one thousand people. As a child I was an observer and people fascinated me and the Granard of the 1950s is celebrated in the long poem, Diary Of A Town, published in my fifth collection, Curve Of The Moon.

Many of my early poems are based on subject matter retrieved from childhood. Having completed my national school education in Granard, I went as a border to St. Norbert’s College, Kilnacrott, Co. Cavan. Here I spent five years in preparation for the Leaving Certificate Examination. It was a typical boarding school of its time with a strong emphasis on the Catholic religion. I spent one year studying for the priesthood in Maynooth University and left the seminary part of the university to continue my study as a lay student.

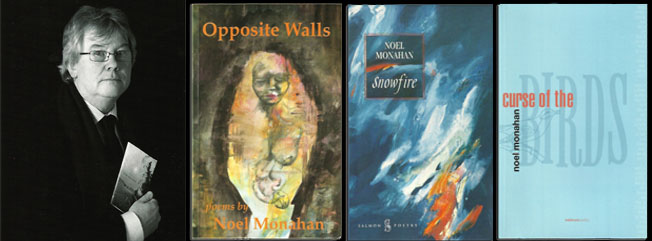

To help fund my education I went to New York in the summer of 1970. Here I developed a deep love and interest in the music of Paul Simon and Bob Dylan and in many ways they were the inspirational poets of my life. Having completed my Diploma in education, I started teaching in St. Clare’s College, Co. Cavan and remained there for thirty six years ending up as Deputy Principal of the College. I directed a number of Musicals in the College: The Mikado, The Sound Of Music, Oliver, Fiddler On The Roof. While teaching I started to write and publish poetry in the literary magazines. And this lead to the publication of my first collection, Opposite Walls, in 1991.

————————————-

Noel Monahan has published five collections of poetry. His next collection: Where The Wind Sleeps, New & Selected Poems, will be published by Salmon in May 2014. His literary awards include: The SeaCat National Award organised by Poetry Ireland, The Hiberno-English Poetry Award, The Irish Writers’ Union Poetry Award, The William Allingham Poetry Award and The Kilkenny Poetry Prize for Poetry. In 2001 he won The PJ O’Connor RTE Radio Drama Award for his play “ Broken Cups” and in 2002 he was awarded The A.S.T.I. Achievements Award for his contribution to literature at home and abroad. In 2012 Noel received an Arts & Entertainment Award from Northern Sound Radio. His work has been translated into Italian, French, Romanian and Russian. His most recent plays include: “ The Children of Lir” performed by Livin’ Dred Theatre and “ Lovely Husbands”, a drama based on Henry James’ work and performed at the inaugural Henry James Literary Festival, 2010. His poetry is now prescribed text for the Leaving Certificate English Course 2011 and 2012. Noel Monahan is co-editor of Windows Publications and he holds an M.A. in Creative Writing.

http://windowspublications.com/noel-monahan/

http://www.askaboutireland.ie/reading-room/arts-literature/irish-writers/writing-in-longford-today/noel-monahan/

http://www.amazon.com/Noel-Monahan/e/B001K7WQ8G

http://www.linkedin.com/pub/noel-monahan/21/815/258

http://www.podcasts.ie/featured-writers/featured-poets/noel-monaghan/

http://www.virtualwriter.net/vw_content.aspx?id=12982

http://www.versedaily.org/2011/aboutnoelmonahancotm.shtml