OCTOBER 2012

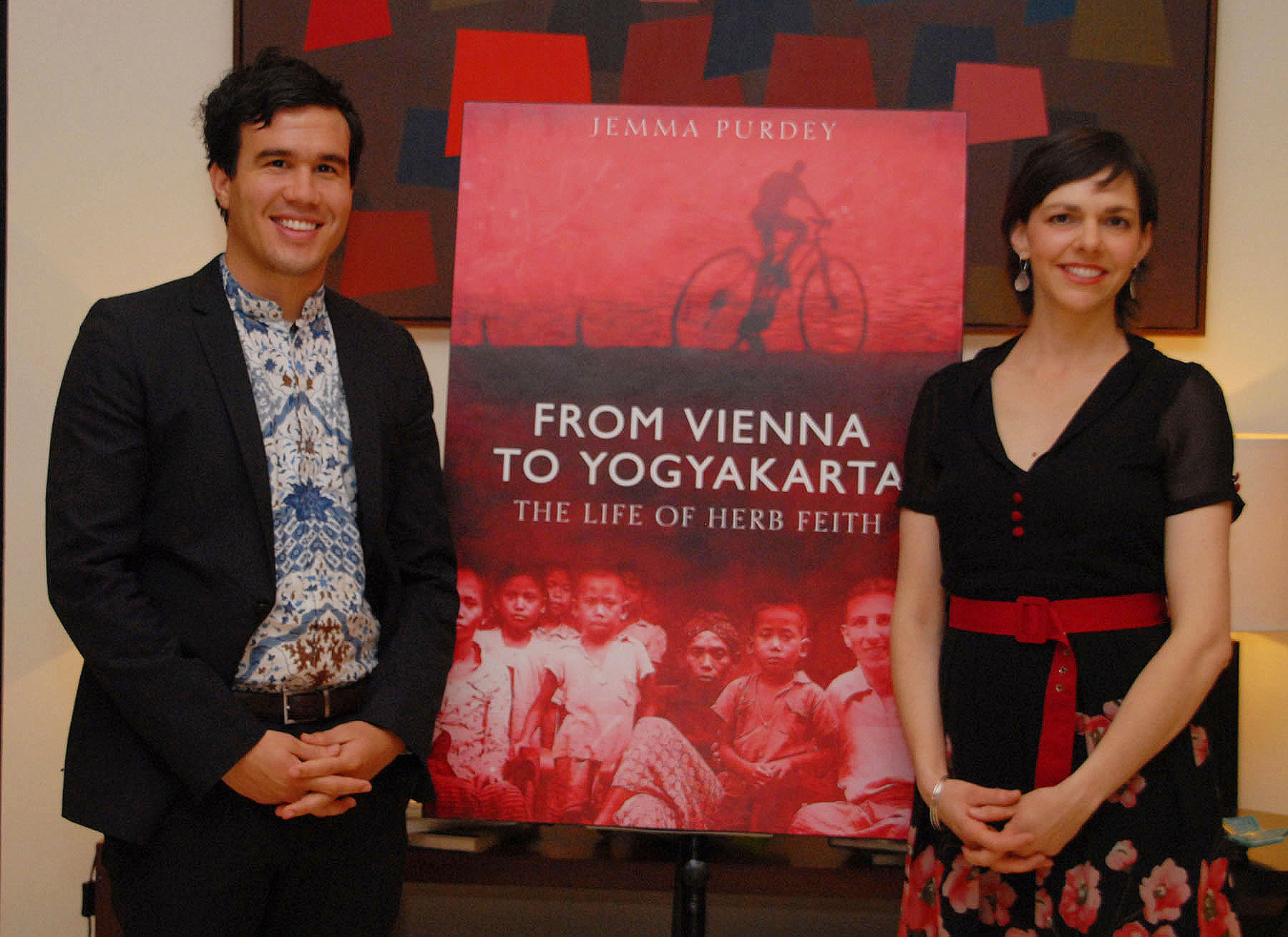

Dr. Jemma Purdey, author of From Vienna to Yogyakarta: The Life of Herb Feith, speaks to Mark Ulyseas

Why are you a writer?

I am a writer by virtue of my deep interest in research and exploring the lives of others through my disciplines in the humanities and social sciences – history and politics with a special focus on Indonesia, human rights and minority rights and empowerment.

Could you tell us about your life and work?

I am an Adjunct Fellow in the School of Political and Social Inquiry, Monash University.

I come from Kyabram, a small town in northern Victoria. As a teenager I developed a keen concern for social justice and was particularly involved in Amnesty International’s campaigns to free political prisoners around the world. Like most young Australians my age I was also impatient to explore the world through study and travel.

After my secondary education I moved to Melbourne University where I undertook an Arts degree with a major in politics and Indonesian language. This was the early 1990s and my interest in human rights had led to further concern for the plight of East Timor and Indonesia’s repressive political system at that time. During my undergraduate years I travelled to Indonesia several times. I wrote my honours degree on challenges to the new Order’s tightly controlled system of political parties and ‘festival of democracy’ in, what was to turn out to be, the last years and months of the Suharto regime. History intervened to guide the direction of my research as the Suharto government’s hold on power began to slip with the Asian economic crisis and eventually saw him fall in May 1998.

Under the guidance of my teacher Charles Coppel, I conceived a topic for my PhD dissertation around the increased levels of anti-Chinese violence and sentiment in Indonesia at this time, not knowing then that Suharto would finally resign following mass rioting in several cities, largely targeting ethnic Chinese Indonesians. My thesis was later published as Anti-Chinese violence in Indonesia, 1996-1999, NUS Publishing, Singapore, 2006.

Following my PhD I spent time living in France and the Netherlands, where I was a fellow at IIAS Leiden. I also lived for an extended period in Mumbai, where I worked as a volunteer teacher at a school for slum children and as a researcher for a women’s library and resource centre. In India I wrote several articles for local and international online publications related to film, society and politics.

I began the Herb Feith biography project in early 2005. It was published in mid-2011 and launched in Canberra at Parliament House, at Monash University in Melbourne, in Dili, East Timor and in Jakarta at a reception hosted by the Australian Ambassador to Indonesia.

I live in Melbourne with my husband and three children, Ernest, 6 years, Roxanne, 3 years and Gabriel, 12 months.

Why did you write from Vienna to Yogyakarta: The Life of Herb Feith? Kindly share with us a detailed overview of your book.

Herb Feith was a pioneer of Indonesian studies in Australia and particularly at Monash University where he taught for 25 years, beginning in the mid-1960s. In late 2004, the Centre of Southeast Asian Studies at Monash (co-founded by Feith) called for applicants to write his biography. It was an honour and a privilege for me to be selected to write Herb Feith’s biography. My background in Indonesian studies and long held interest in social justice and human rights were deemed a good fit for the task at hand. I had personally met Feith on only a few occasions, but as for any student of Indonesian politics, his work on the parliamentary democracy period was a seminal account. Moreover, my supervisor at Melbourne University, Associate Professor Charles Coppel had himself been a student of Feith’s, so I liked to imagine we had an anak buah connection!

The biography celebrates Herb Feith as a pioneer with a lasting legacy linking Australia to Indonesia, Timor Leste and the developing world more broadly. He was an internationalist. He was in part, a man of his times – a young educated adult in the late 1940s and early 1950s when Australia and Australians were looking outwardly in order to define our own identity and place in the world and the region; but he was also a man before his time – a true global citizen who saw Australia as but one nation of many, albeit one which had peoples of such levels of education, commitment and wealth to make a significant difference for so many in the developing world. As a young man in his twenties and as he matured into his middle and older age, Herb never lost sight of his desire to learn from people from all walks of life and cultures.

I write in the introduction to the book how Herb had an inbuilt ability to cross-cultures, which undoubtedly came from his own personal experience of crossing from Central European Jewish culture to Australian urban life as an 8 year old boy in the war years. His particular and special gift though, was one of a deep and authentic interest in other people and what they thought, and an ability to empathise. As Peter Britton puts it, Herb engaged in ‘active listening’ and so endeared many people to him, whilst learning a great deal about the world and its diversity of views.

Herb Feith first went to Indonesia in June 1951. He was 20 years old and a recent political science graduate and the first Australian graduate volunteer of what would one day become the large organisation Australian Volunteers International. He worked in the Ministry for Information alongside another Australian, Molly Bondan. He cast his eye across Jakarta and saw a world of possibilities for his fellow Australian graduates who wanted to come to Indonesia to help build the fledgling Republic.

He described his first weeks in Indonesia as some of the most exciting and exhilarating of his life. His letters to his friends and family reveal that he was immediately and deeply engaged with his work, with the people he met and with the social problems he saw, which he very quickly took on as his own. He never lost this initial passion for solving Indonesia’s problems as his problems and those of all humanity, nor his particular affection for its people.

In Indonesia in the 1950s, such an approach from a European was a revelation to those Indonesians he worked with and made friends with. Some might also say it was a very Australian approach, embracing the ideas of egalitarianism on which we base our nationalism; and indeed for the thousands of Australians who have followed Herb and the earliest volunteers over the past sixty years to work in countries across the world, this ethos rings loud and true.

Herb understood the true value and wonderful rewards of getting to know deeply Indonesians and their society. His passion for Indonesia and for teaching what he knew was such that in the 1960s, 70s and 80s students came from across Australia, Indonesia and around the world to Monash University to be taught and supervised by him. After his retirement Herb returned to Indonesia in the 1990s as a volunteer lecturer at UGM, and a new generation of Indonesian students were similarly inspired by his great enthusiasm, vast knowledge but also his uniquely generous approach to teaching. Long may this legacy continue in both our countries.

So it is that I hope that the biography also celebrates the shared pursuit by Indonesian and Australian scholars towards improving our knowledge and understanding of each other’s complex societies. A legacy of the work of scholars including Herb, John Legge, Jamie Mackie and the important generation that followed – today Australia boasts as being world-leading in this field of study. But we can’t be complacent and as our senior scholars know very well, political vicissitudes will bring the study of Indonesia in and out of favour with young Australians and test scholars themselves – as Herb was so often tested. For Herb, when it came to facing such challenges, in the end it was his empathy and friendships with Indonesians that led his drive to want to reveal and know more about their ways of seeing the world and about the political regimes under which, for many decades, they lived in struggle. But more than that, Herb never ceased believing that such knowledge could, in the end, be a powerful force for good.

Herb’s career as an Indonesianist spanned over 50 years, beginning with its first, failed attempted at constitutional democracy, until the early years of its current and so far, overwhelmingly successful, democratic system of government. This is then a story of Indonesia’s political journey too.

Very early on in this project I said to my friends that I expected it would be the most challenging work of my life so far. At the end of it, I can say that I was probably right, but at the same time, I can also say it was the most fulfilling and satisfying work experience I could have hoped for. Researching and writing this extraordinary life with all its twists and turns, travels and travails whilst also being able to engage deeply with ‘Indonesia’, its history and politics – which is my discipline of scholarship – was a rare and privileged position to be in. As a subject Herb is just what any author might conjure up; he is complex, brilliant, challenged and challenging, flawed and inspiring. It was good advice I received at the beginning of the project from Jamie Mackie, who was a member of my advisory panel in its early stages. He advised that before I stepped into the archives I should make my first task to interview as many of Herb’s friends, colleagues and family as I could find. Jamie was right.

As I moved around talking to people about Herb he appeared in all this complexity and dynamism before me. I had a good idea of the patterns of his life, the ways people had seen him, loved him, admired and attempted to follow him. Thanks to his family’s generosity and trust in me, I knew also about his love for family and closeness to his own parents, to Betty and his children and grandchildren. I knew about his flaws, his illnesses, his writers-blocks and moments of moral paralysis. The exploration into his archives – a treasure chest of letters, writings and memos – therefore, provided not so much ‘surprises’, as they did substance; deep understanding and insight into his motives, views and responses to events in his life. It was, as I say, a privilege to encounter as a researcher.

What are you working on now?

My first experience writing biography was such a wonderful one that I am now planning to undertake another, which also incorporates my Indonesia interest. My current project – in its very preliminary stages – is a biography of an Indonesian political family or dynasty. As minor aristocracy, the Djojohadikusumo family’s involvement in the elite political sphere of Indonesian society stretches back four generations. Patriarch, Margono Djojohadikusumo, was senior bureaucrat in the Netherlands Indies administration and a nationalist who founded the Bank Negara Indonesia (Indonesian National Bank) upon its declaration of independence.

Two of his younger sons died heroes in the revolutionary struggle against the Dutch occupation in the post-war period, and his eldest son, Soemitro, a Dutch educated economist, served as Minister for finance in various cabinets under the early Sukarno presidency. He was also later a key economic advisor to the Suharto government and is a national hero (pahlawan nasional).

Today Soemitro’s sons, Prabowo Subianto and Hashim Sujono are co-founders of the political party, Gerindra (the Greater Indonesia Movement Party) with a voter-base of farmers, fishers and small business owners. Prabowo leads the party and will run for President in the 2014 election.

Hashim is listed as one of Indonesia’s wealthiest businessmen and Prabowo himself has a vast fortune amassed through their various businesses in palm oil production, coal and natural gas and various agri-businesses. Once married to Suharto’s daughter, Siti Hediati Harijadi (Titiek), Prabowo is a former military commander who held posts as head of elite military units Kopassus and Kostrad with numerous tours in East Timor during the occupation, where he established militia units and fostered protégés including Eurico Guterres. The fourth generation of this family are also heavily involved in the Gerindra party, especially Hashim’s son, Aryo, who is head of the party’s youth wing, Tidar. In their influential book, Reorganising power in Indonesia: the politics of Oligarchy in an age of markets, Robison and Hadiz (2004) describe a “political class” which emerged in the post-colonial period, comprised of those from minor aristocratic backgrounds, members of the colonial bureaucracy and western educated intellectuals.

And before that, as Heather Sutherland describes them in her exemplary study of Java’s colonial bureaucratic elite (1979), this ‘native’ civil service was made up of Java’s aristocratic elite, and “was a continuation of the old governing class and a major source of Java’s modern elite.” The Djojohadikusumo family fits very much within both these categorisation across three generations.

The study seeks to fit within this broader, growing body of work on dynastic or ‘family’ politics in Indonesia, by providing an historical approach through a biography of such an elite family, which, though several of its individual members feature prominently in the national narrative in one way or another, has not yet included a Presidential history. Crucially, however, the family has maintained a close proximity to the centre of political power (as it has shifted and changed) across more than three generations of Indonesian national history. This adaptability is key to understanding how the family has achieved this consistency of power-sharing. What, I am asking, are the ‘family characteristics’, ‘traits’, and narratives that have enabled this?

The decision to research and write a ‘family biography’ is because I believe that a ‘multi-generational past’ is important, if not vital, in the context of the family’s present day tilt at power. It is important for a few reasons. Firstly, and simply, a close study of the generations before Prabowo is key to understanding the political philosophy informing Gerindra and its drive for the Presidency. Secondly, because questions are being asked about Prabowo’s popularity, which remains high in spite of his “colourful past”, as accused human rights violator. What we see is that his individual past or biography has been more or less re-cast or replaced by his ‘family legacy’ of long service, sacrifice and patriotism. By not focusing wholly on the personality of one single representative and leader, but on the line of family members he represents, Gerindra are arguably far better placed in the current Presidential race. Thirdly, within the family, and in the ways it presents itself publicly, family and national histories are important. This is apparent across various themes which can be seen re-occurring within the family’s own narratives about their roles as citizens and patriots, servants and leaders of their nation.

As they emerge as the next most powerful Indonesian dynasty, a closer examination and deeper understanding of this family, their history, values and conceptions of Indonesia’s are vital.

————————————————

Dr. Jemma Purdey is an Adjunct Fellow in the School of Political and Social Inquiry, Monash University. She is author of From Vienna to Yogyakarta: The life of Herb Feith, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2011; Anti-Chinese violence in Indonesia, 1996-1999, NUS Publishing, Singapore, 2006 and editor of Knowing Indonesia: Intersections of self, discipline and nation, Monash Publishing, Clayton, 2012.

Following the completion of her PhD at Melbourne University, on anti-Chinese violence and the fall of the New Order, she was a Fellow at the IIAS in Leiden, The Netherlands, where she developed her wider thematic interest in the study of violence in Indonesia. The following year she accompanied her husband to Mumbai, India where she worked as a volunteer at a school for slum children and at a women’s resource and advocacy centre. During this time her writings were focused on the NGOs where she worked, the Indian film industry and politics.

In 2005 she took up a position at the Centre of Southeast Asian Studies at Monash University, to research and write the life of Herb Feith, Australia’s first and greatly loved Indonesianist. She interviewed more than 100 of his friends, colleagues and former students in Australia, Indonesia, East Timor and elsewhere. In early 2006 as a Harold White Fellow at the National Library of Australia, Jemma had privileged access to Herb’s personal archive.

In 2007 she commenced an Australian Research Council Postdoctoral Fellowship to continue her work on the Feith biography and on a wider research question, ‘Ways of knowing Indonesia: Scholarship and engagement in the Australian academy’. She convened a major conference panel at the ASAA conference in 2008 and edited two publications on these themes including the recently published, Knowing Indonesia: Intersections of self, discipline and nation, Monash Publishing, Clayton, 2012.

Her wider research interests include human rights and minority studies, biography, Indonesian politics, violence and conflict resolution, transitional justice and political dynasty.

She is the Chair of the Board of the Indonesia Resources and Information Program, which publishes the magazine, Inside Indonesia; and a member of the Herb Feith Foundation Board and its Working Committee.