Article in PDF (Download) – LE Mag, June 2012. Also check out his poems here – LE Mag, February 2016

Philip Casey speaks to Mark Ulyseas in an exclusive interview

Well known Irish Poet, Writer, Editor and member of Aosdána, which honours artists whose work has made an outstanding contribution to the Arts in Ireland, speaks candidly on his life, work, Irish Writers Online and A Guide to Irish Culture.

“There are people who think writers are elitist loafers and leeches and never do a day’s work, and while the Catholic Church was at its most powerful and obscurantist in the 1940s and 1950s, books were banned and writers were hounded from their jobs, a notable case being the novelist and short-story writer John McGahern. Most writers of note had to leave the country.

Today is a different matter, and I think there is a general respect for writing as a profession. I know that writing friends from abroad have commented on the fact that if you declare yourself to be a writer in Ireland, nobody thinks it’s strange!”

Could you share with the readers a glimpse of your life and work?

I was born in London in 1950 to Irish parents, grew up in Co Wexford (South-East Ireland) on my parents’ farm, spent a long time in hospital in my teens, and moved to Dublin in 1971. I emigrated to Barcelona in 1974, just as the Franco era was ending, and was at a champagne party the night the Generalissimo died. I returned to Dublin just after the first free elections in Spain in 1974, and after a few years of trying to be respectable, decided I was a round peg in a square hole, and that all I wanted to do was write. I gave up my job, and survived on very little. I was 29, and the following year I published my first book of verse. I’ve since published four collections in all, and three novels. I’ve also written a children’s novel which I hope will be published over the next year or so, and am presently writing non-fiction.

Why do you write?

As a child I told stories to my brothers (my sister was a late arrival) and as a teenager I wrote songs. One night on Irish radio I heard a poetry programme. ‘I can do that,’ I told myself. To put that in context I was living in the countryside with little access to books, TV wasn’t common, and needless to say there was no such thing as the internet. Moreover, I was a late starter in secondary school because of long periods in hospital, and was only vaguely aware of literature until I did. So I’ve always had the impulse to create. Actually while I was in hospital for the third time in my teens I won my first literary prize – for an essay on Keats.

I always try to avoid writing, especially novels or non-fiction. It’s only when I’ve nowhere else to turn that I give in and write. Perhaps it’s a delay tactic to wait until I’m ready to write! On the other hand if I don’t write or am prevented from writing by one circumstance or another, I get ill. I’d like to get back to writing poems, but I’ve written only a handful since my last collection, and there’s a novel I want to write after I’ve finished the present non-fiction work.

In a nutshell I write because I have to and I don’t really want to do anything else.

Is there such a thing as a full time poet or writer?

I certainly think of myself as a full-time writer. Of course, like most writers I can spend a long time staring through windows, friends often call unannounced, I’m asked to read a lot of manuscripts, or books, and there are a million excuses not to write. So it’s not like a proper job, 9-5. On the other hand, a writer is always on call, so to speak. And reading and dreaming is a significant part of being a writer – maybe even more so for a poet. The peculiar thing about poetry is that a lifetime’s experience can be distilled into a few lines, though I think any poet is lucky if he or she leaves behind one durable poem. To leave more than half a dozen durable poems is to be a great poet.

What is the responsibility of a poet or writer to society?

I think a lot about society, both in Ireland and abroad. I’m very interested in history and politics, and having lived through the dying days of Fascism in Spain, I’m worried about its resurgence in Europe and how so-called austerity is facilitating its success. I’m passionate about creating a world without fossil fuels. I’m optimistic about how technology can help create a better world if it is matched with a generous society. Yet I think it would be a mistake for me to enter politics per se. I hope I can best contribute to society through what I think I do best – my literary work. My current non-fiction is on an aspect of Irish history both in Ireland itself and amongst the Irish diaspora, which I hope will make readers think about how ‘the other’ is treated in society. How one treats ‘the other’ is a fundamental measure of any society.

When did you start Irish Writers Online?

I’m not sure exactly when I started Irish Writers Online. The Internet Archive has a record of 20th Century Irish Writers, which is what it was called then, from 1999, but I think I started it a few years earlier. I had learned some basic html, and had made a little website for myself called The Fabulists, after my first novel, and I thought as I was promoting my own work, why not promote that of my writer friends too?

Naturally I had to call it something else once the 20th century ended, and so Irish Writers Online was born, with its own dedicated website. It is now accessed by lovers of literature, students, academics, writers and media from all over the world, and presently lists concise bio-biblio-graphies of more than 600 Irish writers. I’ve lately been adding images and videos where they are available.

Irish Culture Guide is its sister site, and that has over 1,000 descriptive links to websites featuring aspects of Irish Culture. It’s not quite as well-known as Irish Writers Online but has been gaining slowly in popularity.

Does the Irish Literary community get funding from either the State or Private donors?

There are various private sponsors such as Hennessey Brandy, which co-sponsors with state bodies the New Irish Writing series, long established in various Irish newspapers, and most recently in The Irish Independent. The Irish Times, for example, has also sponsored prizes for both fiction and poetry, as well as the annual theatre awards. There are also prizes The Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award which is the richest of its kind in the world, though of course that is open to international writers also. However Irish writer Edna O’Brien won it in 2011. Then there is The Michael Harnett Award for poetry, commemorating perhaps the finest Irish poet in both languages. The main funding for literature, however, is from the State in the form of bursaries and support for publication of books and magazines.

It also funds a unique institution known as Aosdána. The word comes from an ancient Irish term for people of the arts, aes dána. It honours those artists whose work has made an outstanding contribution to the arts in Ireland, and encourages and assists members in devoting their energies fully to their art. Those whose income is solely from writing and/or is below a certain threshold, receive a stipend known as the cnuas. I’m privileged to be a member of Aosdána and can vouch that its monetary support changed my life.

Has the internet helped promote the Irish literary community monetarily? And has the growing popularity of the Kindle affected the sale of printed books?

I don’t know if I can answer this question directly. Of course it has helped writers in all sorts of ways, from cutting postage costs (most agents and publishers accept email submissions now), facilitating newsletters, to readers buying their books on Amazon or Irish web shops or indeed directly from their publishers – you can see a list of both Irish bookshops on the web and Irish publishers at the bottom of the page on Irish Writers Online. Many, not most, Irish writers have their own website, and some, not many, are on Facebook and Twitter. In other words, Irish writers are like writers in most countries in this regard. As for ebooks, I see some writers publishing direct to Kindle, but as yet not many. I don’t own a Kindle and probably won’t, as I believe in open formats and I distrust the Kindle’s proprietary format . I do however sometimes read ebooks, mostly free classics, on my old smart phone and I think as the technology evolves and open formats become better appreciated then writers will be more comfortable with e-publishing.

We are all caught up in the great wild web and this has given rise to copyright infringement and plagiarism. How has it affected the Irish literary community?

There was some concern and puzzlement about the Google Books Agreement a year or two ago, but otherwise I’m not aware of significant copyright infringement or plagiarism. Which is not to say that it doesn’t exist. Several Irish writers including myself have made some of our work freely available under a Creative Commons Licence, which allows a reader to download the work and distribute it but (in our case) not change it or profit from it. Have a look at Irish Literary Revival and my own website and the Creative Commons website for more detail.

Do you think Media (Print and Electronic) in Ireland has helped promote writers and poets? And can they do more for the struggling community?

Of course there’s always a clamour for more to be done, but I think Ireland is relatively fortunate in that the media, particularly The Irish Times, give good coverage of books, and usually publishes a poem every week, and now that the Irish Independent has recently taken on New Irish Writing, it has made up for its previous scant coverage of Irish literary work. The main Irish TV station, RTÉ, no longer has a dedicated books program, alas, but its main arts presenter John Kelly is a novelist himself and is sympathetic to literature and covers it when he can, I think. Of course if a writer wins a significant prize, then that’s big news.

In your opinion how do people view writers and poets today? Do they view them as catalysts for change?

There are people who think writers are elitist loafers and leeches and never do a day’s work, and while the Catholic Church was at its most powerful and obscurantist in the 1940s and 1950s, books were banned and writers were hounded from their jobs, a notable case being the novelist and short-story writer John Macgahern. Most writers of note had to leave the country. Today is a different matter, and I think there is a general respect for writing as a profession. I know that writing friends from abroad have commented on the fact that if you declare yourself to be a writer in Ireland, nobody thinks it’s strange!

———————————————-

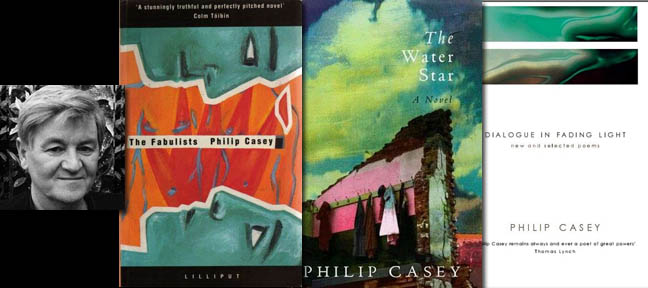

Philip Casey has published four collections of poetry, including Dialogue in Fading Light (New Island Books, 2005), and three novels, The Fabulists (Lilliput 1994), The Water Star (Picador, 1991) and The Fisher Child (Picador, 2001). He has completed a children’s novel and is currently writing non-fiction. He’s a member of Aosdána, and lives in Dublin.

Philip Casey’s website . Irish Writers Online . A Guide to Irish Culture . Twitter.com@philip_casey.

4 Replies to “Philip Casey in an exclusive interview”