MAY 2010

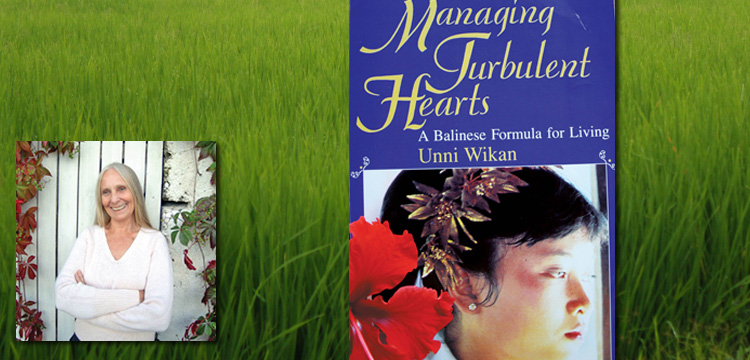

Professor Unni Wikan, celebrated Norwegian anthropologist and author of Managing Turbulent Hearts – A Balinese Formula for Living speaks to Mark Ulyseas in an exclusive interview. Thanks to Terje Holte Nilsen for making this happen. (This interview was published in 2009, Bali, Indonesia)

MU – Many visitors, women being in the majority, view Bali as a ‘feminine’ island with a culture that is all embracing. Do you feel that the increasing number of immigrants to this island will dilute or distort this culture? And will it (Balinese culture) morph into a more aggressive form thereby seeing a clash of cultures?

UW – I never thought of Bali as a ´feminine´ island; to me, such a concept does not make sense. Bali is a rich and complex civilization with a multitude of ways and “cultures” being practiced, some of them strongly patriarchal. I do not think that immigration as such presents a danger to this remarkable Culture. On the other hand, the exposure of youth to manifold influences through globalization, modern forms of communication, tourism etc. will undoubtedly have its impact, in Bali as elsewhere. We cannot say at this point in time what will emerge. It is not just a question of what happens in Bali but in the wider world.

MU – Do you think that the concrete jungle that is growing across the isle will alienate the Balinese with the growing influence of the “hotel and villa” culture? And what, if any, is the way out?

UW – I wish I had the answer to your question for there is clearly the danger that you point to. The Balinese have traditionally lived in close harmony with nature; you couldn´t cut down a tree or erect a building, even a hut, without appeasing and taking permission from supernatural spirits. The “hotel and villa” culture is fundamentally transforming the land and disturbing spirits that used to belong in certain places and that are a part of Balinese cosmology. On the other hand, the Balinese resemble other humans in that they are pragmatic, and these new developments offer jobs to many people. There is no win-win situation.

MU – Many long time residents believe the Balinese must be more pragmatic in terms of rescinding their responsibilities of the numerous mandatory attendances at religious ceremonies for the responsibilities of a job? Please comment.

UW – This is a challenge in many societies, how to accommodate job obligations with religious or ritual observances. I did fieldwork in Bhutan, a Buddhist country, and the same concern arose there: what could be required of job attendance of people who every so often had other “legitimate” ritual concerns. Or take Muslims in Norway, my country: praying five times a day at specific intervals is not easily combined with many kinds of job. Solutions must be found and generally, religions can be flexible: they are, after all, partly man-made.

MU – There appears to be a growing gap between the haves and have not’s – the former being expats and the latter, Balinese. Do you think that this will lead to a backlash that will see a rise in criminal activities and in general disrespect for the Tamu (guest) leading to law and order problems?

UW – We see such problems emerging in many societies, they seem to be part and parcel of globalization. Organized, transnational crime is also on the rise everywhere. What is special about Bali, as I know it, is how peaceful and orderly the island still is. But one should be aware. Large-scale tourism naturally changes people´s perceptions of the Tamu, and the way many tourists (and some expats) behave further creates disrespect.

MU – Some say that marriages between expats and Balinese, where the age gap being a generation or two is abhorrent and should be curtailed; often these marriages are not legalized with competent authorities from the foreign embassies thereby disenfranchising the offspring from their rights to citizenship of the foreign country from which one parent comes from. Are we witnessing the birth of a generation existing between the gaps in society? And will these children of the morrow become the catalyst for change? And what change do you perceive this to be?

UW – I do not have first-hand knowledge of such cases, therefore it is hard for me to think through the implications with regard to Bali. Not having a legalized marriage is, however, a problem that many people in many countries are dealing with, and there is much international discussion of how to secure the rights of the child to paternity, inheritance and citizenship. Recently, there was a case in Egypt where a woman went to court because the man, with whom she had entered into a non-legalized (so called traditional – urfi – marriage) denied the child he had fathered paternity. In this case, both were Egyptians. She won, and has become an exemplar for others. I believe women can become the catalysts for change.

MU – “I will not blame the rapes on Norwegian women. But Norwegian women must understand that we live in a Multicultural society and adapt themselves to it.” “Norwegian women must take their share of responsibility for these rapes.” You stated this in reference to high profile incidents in Norway involving immigrant men and the local (Norwegian) women. Do you think the reverse will happen in Bali, like attacks on ‘visitor women scantily clad’ by ‘locals’ because the ‘visitors’ have shown ignorance of the social norms and/or not understood the prevalent culture?

UW – I have never said that women must take their share of responsibility for rapes. This is sheer misrepresentation of my statement. The rapist bears full responsibility for rape, which is a crime. What I did say was that many immigrants come from societies where the way many Norwegian women dress and behave is misunderstood to mean that they are immoral. In a multicultural society, it is an advantage if people learn something about one another´s codes of communication. The same applies if you are a tourist. It is a sad fact of life that women are exposed much more than men to sexual violence. So women need to be careful, and knowledge is power. But full responsibility for rape resides with the rapist.

MU – Is then, cultural clashes and clichés the raison d’être for an emerging ‘irrational society’?

UW – No, I wouldn´t use such a term. Society is not “irrational” but persons can be. However, rape does not have to do with irrationality. It is a crime usually committed by wholly rational people.

MU – You have written a number of books that have thrown light on the travails and tribulations and the constant fight for survival between man and woman in societies that discriminate. Does your book “Behind the veil in Arabia: Women of Oman” shed light or reflect the state of women in general in societies across the world like India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq and beyond? And is the treatment of women in a society reflective of its ethos?

UW – Oman is special. It was, and continues to be to me an exemplar of a good Muslim society where women are well respected and treated. Oman has an enlightened ruler, Sultan Qaboos bin Said, who has had the power for nearly forty years, and has done a world of good for his country, including women. Yes, there is an ethos in Oman that underscores gracious behavior and that is reflected in the treatment of women. It is different from what you find in many other parts of the Muslim world, local culture and religion always intersect, and so Oman is quite different from not just Afghanistan or Iran, but also its neighbor, Saudi Arabia. That said, there are also similarities: Polygamy – a man´s right to have several wives simultaneously – still holds in many parts of the Muslim and non-Muslim world, Oman included. Men are privileged in numerous ways. But Oman could point the way to what other traditional societies, more harsh to women – Muslim, Hindu, Christian etc. – can become.

MU – What is the role of a culture? Does it create, give birth to or is it a matrix in which we are all born? And does this matrix hamstring enlightenment/progress in all parameters of society?

UW – We are born into cultures; I was born on an island in the Arctic Ocean in a part of Norway called the Land of the Midnight Sun, and my view on the world is profoundly shaped by the influences I came under through my formative 18 years there. But cultures are ever changing, just like people; indeed, it is people who make up cultures, we are the agents, culture in itself can do nothing, it is just a word, a concept. It is important to keep this in mind: People have in their power to create and make “culture” happen, for good or bad. Therefore too, culture clash is not a term I use: it indicates that there is something there with the power to act by itself. Think of people instead, and you have a better instrument for building peace.

MU – As a celebrated and highly respected anthropologist do you think that Bali will survive the onslaught of the continuing influx of alien cultures bombarding the island; and will this be the beginning of a convergence that will bring about a new evolved society or will it be another reason for a conflict of cultures?

UW – Bali has withstood a continuing influx of alien cultures for a long time in history. That gives me hope for the future of this gem of a civilization. Bali is bound to go on changing and evolving; and society fifty years from now will be different from the one we know. But I believe there is a solid core that is sustainable and that may even take on a stronger identity as “Balinese” as cultures mix and mingle. Or, I should rather say, as people from different cultures mix and mingle. My husband, Fredrik Barth, wrote a book called “Balinese Worlds”, plain and simple. That says it all: Bali consists of many worlds, many cultural traditions that have co-existed, competed, and also enriched one another. This is due to the resourcefulness and tolerance of Balinese people.

MU – What are you working on now and will you be visiting Bali in the near future?

UW – I have just finished two books – one published in the US, the other in Norway, on honor killings in present-day Europe. A sad topic I never planned to handle but that became urgent with the murders of several young girls by their (immigrant) families in Europe. One is called In Honor of Fadime: Murder and Shame and deals with the fate of a young Swedish-Kurdish woman who was killed by her own father because she had “dishonored” her family by choosing her own love in life and refusing a forced marriage to a cousin. Her story made the international community wake up to the fact that honor killings do not just belong to “them” but to “us” in the West, and has helped to put the problem on the international agenda. Now I am about to do something much more pleasant: embark on a long fieldtrip to Arabia (Yemen, Oman and Saudi Arabia) to explore ideas of freedom and dignity post 9/11, and to see how these ideas are put into practice in various walks of life. As an Arabic speaker I can work without interpreters and as a woman, I have easy access to people, I am not considered a threat. Among places I will visit is the Hadramawt in North Yemen where some families I know in Singaraja originally came from so I will explore the links; there have been close connections between inner Arabia and Indonesia for centuries, with influences going both ways. I have also an ongoing project in Bhutan, a Buddhist kingdom in the Himalayas, where I have spent much time to explore culture and religion.

I was last in Bali a year ago, and hope to return later this year.

It is very much a part of my heart.

———————

The author Unni Wikan is Professor in the Institute of Ethnography at the University of Oslo, Norway. Her books include – Behind the Veil in Arabia: Women in Oman and Tomorrow, God Willing: Self-made Destinies in Cairo. All the above mentioned books have been published by The University of Chicago Press, U.S.A

© Mark Ulyseas