Article in PDF (Download)

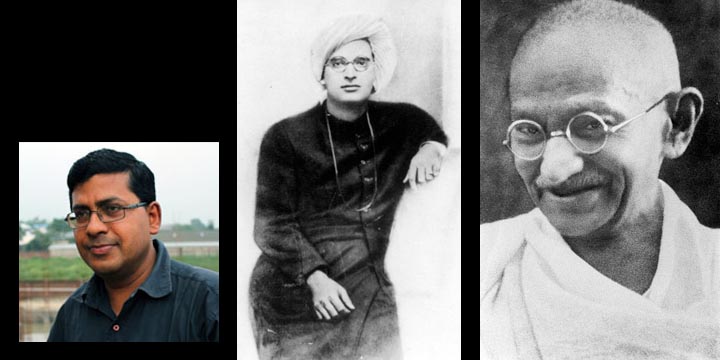

Mahatma Gandhi and Dilip Kumar Roy – Fateful Days – Romit Bagchi

With Hindutva being again on the ascendant curve, occupying India’s prime politico-ideological space, it would not be out of place to recall the predicament of Mahatma Gandhi and the animosity dogging his prayer meetings in Delhi in the immediate aftermath of Independence. People, by and large, were seething with anger with the Congress and, particularly, with Gandhi, for they felt that they had supinely acquiesced, if not treacherously engineered, the partitioned freedom that had left a gory trail of massacres and sufferings for millions of people. Jawaharlal Nehru admitted to Krishna Menon, his friend, “The partition business has excited Hindus tremendously and their wrath has turned against the Congress which is supposed to be guilty of agreeing to this partition.” Many opined that but for the benumbing shock thrown upon the nation’s conscience by Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination, the forces representing Hindutva would have gained momentum at the expense of the Congress.

Dilip Kumar Roy, son of the legendary Bengali poet, composer and playwright, Dwijendralal Roy, drew a graphic pen-picture of what was happening at the Mahatma’s prayer meetings in Delhi in those fateful days in his book, ‘Among The Great.’ Aside from being a reputed writer, Roy was a gifted singer about whom Gandhi wrote, “…though I am no connoisseur of music I may make bold to claim that very few persons in India-or rather in the world-have a voice like his, so rich, sweet and intense.” Besides, he was a dearly loved disciple of Sri Aurobindo and a very intimate friend of Subhas Chandra Bose.

Roy met the Mahatma several times, beginning from Poona where the latter was convalescing then at a government hospital following appendicitis surgery in February 1924. And the final one happened in the last week of October 1947 in Delhi-just three months before the Mahatma fell to the assassin’s bullets. Roy attended the prayer meetings for three consecutive days from 29 October. He sang songs, overwhelming the Mahatma and all others present. Yet, he felt an ominous strain of foreboding, hanging palpably in the air. People, at least a section of them, present at the prayer meetings, were in no mood to countenance Gandhi ‘inflicting’ Quran verses on them.

“Next evening I arrived at the Birla House a good quarter of an hour before time. The audience was even more impressive than on the evening of my first visit, but the atmosphere was disquieting. I was told that someone had registered an objection to Quran verses being inflicted on a predominantly Hindu audience and so it was on the cards that Gandhiji might not be holding the prayer at all. They pointed out to me the trouble-maker: it was a Sikh stalwart with white beard and sombre face. As I fixed him with my gaze he looked up and our eyes met. Instantly he hoisted himself out of his seat and almost ran up to me in a breathless state.

‘Sir!’ he roared angrily. ‘You are a sadhu and so must adjudicate. I appeal to you on bended knees to be fair. Tell me, is it right to foist on us, the Hindus, verses from the scriptures of those who have massacred us ruthlessly, desecrated our homes…Won’t it be a slur on our honour and our manhood to have to listen after all this to this abomination…’

I restrained him in the middle of his fiery speech. ‘But be quiet, my kind sir,’ I demurred.

‘But why shouldn’t I?’ he flashed back. ‘I came here to hear Mahatmaji, not Quran verses.’

‘But you knew he insists on reading the Quran verses. So the better course for you would have been to stay away since you feel as you do…’ Then placing hand on his shoulder, I added: ‘You will at least hear me sing the name of God, won’t you?’

‘I’d love to, provided you do not bring in the Muslim God.’

I couldn’t help but laugh and answered: ‘But there is only one God, you know.’

‘I do,’ he returned,’ ‘but…’

‘Calm yourself, my friend,’ I replied helplessly; then I asked him to take his seat, adding that I was going to sing of Krishna.

His face brightened. ‘Splendid’ he cried. ‘And I‘ll listen the whole night…’”

But Roy was singularly unconvinced of the efficacy of the Gandhian shibboleths. “It was worse than useless to attempt what was exceedingly difficult –the reconciling of irreconcilables- by a means which almost guaranteed failure…Anyone who could feel the pulse of the country knew-which the newspapers tried desperately to hide-that the Hindus have been growing restive all over India. Also I wondered how Mahatmaji could have lost sight of this simple fact that where love was intense it turned into hatred almost overnight when frustrated or thwarted. It was evident that those who had come to hear him loved him, but that was precisely why they all felt so bitter against him for having let them down for no reason they could discover,” he wrote.

Yet, at the same time, Roy could not help being moved by the Mahatma, ploughing his lonely furrows in the wasteland of communally frenzied India. “When I left him, my eyes were moist with tears. I was moved by him as never before. And though I tried hard, I could not shake off the suggestion that I would never see him again.”

Gandhi’s view of India’s composite nationalism was invincible. It remained unshaken to the very end despite momentous challenges thrown to it from time to time in course of the sub-continent’s tumultuous communal history. “I have not lost hope that I shall live to see real unity established between not only Hindus and Muslims but all the communities that make India a nation…All those who were born in this country and claim her as their motherland, whether they be Hindus, Muslims, Parsis, Christians, Jains or Sikhs, are equally her children and are, therefore, brothers, united together with a bond stronger than that of blood,” he stated.

But the problem is that he could do nothing when communalism of both varieties-Hindu and Muslim, running counter to the Gandhian axioms, came to the fore, save for mouthing lofty, yet ineffectual platitudes and for banking helplessly, pathetically on the good sense of the belligerent communities-bent on slitting each other’s throats in the name of their respective religions.

Roy was deeply worried about the Mahatma too. “The reason was this. Some years ago, somebody in our Ashram (at Pondicherry) had seen a prophetic vision…The vision was not concocted after the event; it had been published in the 1920s in a well-known (Bengali) book entitled ‘Unapanchasi’ whose author, a celebrated writer and a quondam disciple of Sri Aurobindo, is noted as a man of keen intellect and great integrity of character…The vision he had recorded was that directly after the liberation of India from the foreign yoke a very eminent man ‘in white homespun’ would be shot dead in a public meeting. As I heard his (Gandhi’s) address (at the prayer meetings) I could not dismiss the vision,” Roy wrote.

Gandhi, aware as he was of his helplessness, looked melancholy personified those ominous days. “…I had a feeling that with all his brave attempts to hide it, he was weary to the bones…world-weary and…longing for sleep,” Roy recounted.

When the news of the assassination came just three months after the final meeting Roy was giving a lecture-demonstration on Indian and Western melodies at Calcutta University. “The meeting was dissolved and a boy went hysterical. Gloom descended on us all. On my way back home I was struck by a coincidence: the song I had composed and was going to sing was a mystic dialogue between Mother and Child:

I will now sleep in thy love’s deep

And toy no more with things that pall.

I have at last heard thy far call.”

© Romit Bagchi