Article in PDF (Download)

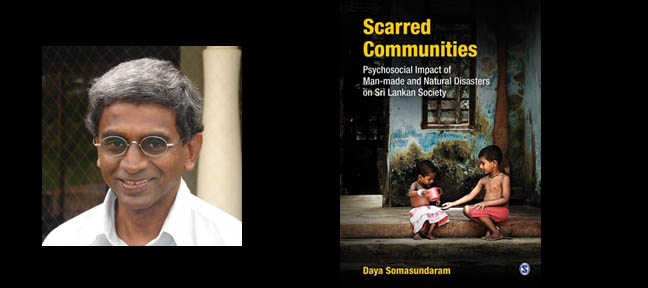

The cover photograph of the book was taken by Dr. Jeewaranga Gunasekera who was the Medical Officer of Mental Health (MOMH), Mannar at that time. The photograph was used as a form of psychoeducation in a poster campaign by the Mental Health Unit of the Regional Director of Health Service (RDHS) in Jaffna to promote the rebuilding and regeneration of the family in a post war context. Health education or psychoeducation is a crucial element of community level psychosocial interventions described in the book. We thank Daya Somasundaram for contributing this article that gives us an insight into his book, Scarred Communities.

Scarred Communities by Dr Daya Somasundaram, Author and Senior Professor of Psychiatry at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna, and consultant psychiatrist working in northern Sri Lanka for over two decades. Published by Sage Publications

Scarred Communities is a qualitative, psycho-ecological study of the long term effects of disasters, both manmade[1] and natural, on Sri Lankan communities. The concept of collective trauma is introduced to provide a framework to understand how basic social processes, relationships and networks are changed by the impact of disasters. The methodology employed is a naturalistic, psychosocial ethno-graphy in Northern Sri Lanka during the time the author was actively involved in psychosocial and community mental health programmes among the Tamil community.

Participatory observation, key informant interviews and focus group discussion with community level relief and rehabilitation workers and government and non-governmental officials were used to gather data. Shorter forms of the contents in several of the chapters were published earlier in peer reviewed international journals. The feedback and reviews from the publications were used modify and expand on the texts, add additional material and new sections to produce the book.

The main theme is the impact of the two disasters, the Asian Tsunami of 2004 and the chronic civil war that devastated Sri Lanka, mainly the north and east of Sri Lanka. It analyses the various causes of modern civil war, ethnic consciousness, terror and counter insurgency operations and the consequences for communities. The last chapter explores the various psychosocial interventions at a community level. It is a sequel to an earlier book, Scarred Minds, published by SAGE, New Delhi in 1998 that described the effects of the chronic civil war on individuals. The forward by Ashis Nandy is an insightful perspective on the role of psychiatrist in dealing with political violence in a South Asian context.

In the Background section, the phenomena of Ethnic Consciousness is described as the cause of polarization, ethnic tensions, conflict and war. Perceptions based on current socio-political, historical and psychological factors mold of ethnic and national perceptions, consciousness, and events, causing conflict. Terror and Counter Terror are techniques and strategies used in the ethnic conflict by the state and other actors in the struggle for power. Issues of human rights, collective rights, democracy, and terrorism can be understood within a local, regional and international perspectives using counter insurgency discourse.

Theoretically, complex situations that follow war and natural disasters have a psychosocial impact on not only the individual but also on the family, community and society. Just as the mental health effects on the individual psyche can result in non-pathological distress as well as a variety of psychiatric disorders; massive and widespread trauma and loss can impact on family and social processes causing changes at the family, community and societal levels that can be called collective trauma.

The concept of collective trauma is being introduced for the first time in a modern mental health diagnostic classification in the draft of the WHO ICD 11th revision’s guidelines [2] for PTSD under cultural considerations:

“Large-scale traumatic events and disasters affect families and society. In collectivistic or sociocentric cultures, this impact can be profound. Far-reaching changes in family and community relationships, institutions, practices, and social resources can result in consequences such as loss of communality, tearing of the social fabric, cultural bereavement and collective trauma. For example, in indigenous and other communities that have been persecuted over long periods there is preliminary evidence for trans-generational effects of historical trauma.

Supra-individual effects can manifest in a variety of forms, including collective distrust; loss of motivation; loss of beliefs, values and norms; learned helplessness; anti-social behaviour; substance abuse; gender-based violence; child abuse; and suicidality. These effects, as well as real or perceived family and social support, can also impact on individual resilience and outcomes”.

Though both the American DSM and WHO ICD classification systems have traditionally been exclusively individual based, it is argued that a collective approach becomes paramount from a public mentalhealth perspective where large populations are affected and where resources are limited.[3]Further, community based approaches maybe more effective and meaningful in collectivistic societies. The book describes in detail the theoretical underpinnings of the concept of collective trauma and describes various psychosocial interventions that were used in Northern Sri Lanka to counteract its effects.

The methodology employed in the book is basically a qualitative, ecological study that uses a naturalistic, psychosocial ethnography in Northern Sri Lanka, while the author was actively involved in psychosocial and community mental health programmes among the Tamil community. Participatory observation, key informant interviews and focus group discussion with community level relief and rehabilitation workers and government and non-governmental officials were used to gather data. The effects on the community of the chronic, man-made disaster, war, in Northern Sri Lanka were compared with the contexts found before the war and after the tsunami.

A poignant context for the development of collective trauma was what happened in the Vanni. From January to May, 2009, a population of 300,000 in the Vanni, northern Sri Lanka underwent multiple displacements, deaths, injuries, deprivation of water, food, medical care and other basic needs caught between the shelling and bombings of the state forces and the LTTE which forcefully recruited men, women and children to fight on the frontlines and held the rest hostage.

The book explores the long term psychosocial and mental health consequences of exposure to massive, existential trauma through qualitative inquiry using narratives and observations obtained through participant observation; in depth interviews; key informant, family and extended family interviews; and focus groups using a prescribed, semi structured open ended questionnaire.

The narratives, drawings, letters and poems as well as data from observations, key informant interviews, extended family and focus group discussions show considerable impact at the family and community. The family and community relationships, networks, processes and structures are destroyed. There develops collective symptoms of despair, passivity, silence, loss of values and ethical mores, amotivation, dependency on external assistance, but also resilience and post-traumatic growth. Considering the severity of family and community level adverse effects and implication for resettlement, rehabilitation, and development programmes; interventions for healing of memories, psychosocial regeneration of the family and community structures and processes are essential.

Another context for collective trauma was the Asian Tsunami of 2004. Although people in Sri Lanka had experienced major disasters throughout history, it was only after the 2004 tsunami that mental health consequences of a disaster became obvious to all and interventions developed. The impact of the disaster was seen at the individual, family, and community levels. Surveys showed that survivors have experienced widespread traumatization, with high levels of somatization, anxiety, depression, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Phobias, and alcohol abuse. The functioning family had been affected in many ways, with death of multiple members, causing fundamental pathology in family dynamics. Displacement, life in refugee camps, separations, problems of coping faced by surviving male widows, and break up of community life have contributed to disturbances in the family and community.

At the social level, manifestations of collective trauma such as fear of the sea, lack of motivation, guilt, and dependence on outside help, suicidal tendencies are particularly worrying. Psychosocial forms of therapy like counselling, bereavement therapy, family therapy, relaxation, emotive methods like play, art and drama for children and rehabilitation using a multidisciplinary team are more effective for traumatized individuals. The more severely affected, such as those suffering from clinical PTSD or Depression will benefit from pharmacotherapy and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. At the community level, psychoeducation, training of community level workers in basic mental health, promoting family unity, group therapy, relaxation methods, cultural rituals and traditional healing and rehabilitation were useful.

Collective trauma arises from a context that included repressive ecology. Some of these repressive measures in society are disappearances described by Sivayokan with the man author. A community under long term repression responds with youth rebellion and defiance. In the Tamil community this has manifested as militancy. Enforced disappearances (or involuntary disappearances) has become a well-known phenomenon in Sri Lanka for more than three decades. From time to time, Sri Lanka experienced large scale disappearances, connected to the politico – military situation of the country and confined to different localities of the country.

For the first time in Sri Lanka, people come to know about mass disappearances during the 1977 JVP insurgency which was successfully crushed by the Sri Lankan forces. Thousands of youths were reported missing. Then the same fate started happening to many Tamil speaking youths since early eighties which evidently increased after the 1983 riots and the escalation of armed conflict. Initially those disappeared youths were seen as having connections with the militant organizations. Since then, like in many parts of the world, ‘disappearance’ has become a strategy of counter terrorism and was systematically used to suppress the opposition and to terrorize the society. Ironically during late 80’s the militant organizations too were known to adapt this inhumane, cruel phenomenon to deal with their opponents, suspected informants and their own ‘traitors’.

Increasing discrimination, state humiliation and violence against the minority Tamils brought out a militancy among the youth. The underlying socio-political and economical factors in the North and East of Sri Lanka that caused the militancy at the onset are examined. Some of these factors that were the cause of or consequent to the conflict include: extrajudicial killing of one or both parents or relations by the state; separations, destruction of home and belongings during the war; displacement; lack of adequate or nutritious food; ill health; economic difficulties; lack of access to education; not seeing any avenues for future employment and advancement; social and political oppression; and facing harassment, detention and death. At the same time, the Tamil militants have used various psychological methods to entice youth, children and women to join and become suicide bombers. Public displays of war paraphernalia, posters of fallen heroes, speeches and video, particularly in schools and community gatherings, heroic songs and stories, public funeral rites and annual remembrance ceremonies draw out feelings of patriotism and create a martyr cult.

Special contributions to the book by Ruwan Jayatunga describe the mental health impact on the military community in South. Various psychosocial problems including PTSD, Depression, Alcohol abuse and domestic violence can be seen among the military due to war exposure and traumatization. They will need psychosocial rehabilitation to recover and for the community to return to normality. Gameela Samarasinghe describes the challenges in providing psychosocial interventions in a post war context. Ananda Gallapati gives an account of the development of the psychosocial field in Sri Lanka and abroad, the concepts and future directions. Andrew Keef describes Collective Trauma in the Tamil community in London.

When intervening at a collective level, communities can be strengthened through creating awareness, training of community level workers, cultural rituals, social justice and social development. Rachel Tribe, Vijayashankar and Sivajini contribute to the description of the work of Shanthiaham, a local NGO, in providing psychosocial interventions in the north during the war. The widows programme to strengthen war widows by forming a group is one way the rebuild communities. Sivayokan and the author describe the use of drama during the war. Another potent method of intervention was the training of trainers (TOT) who would then train a myriad of local grass root and other workers to look after mental health and psychosocial issues in the community. However, it would be much more effective in the long-term to prevent war by implementing Humanitarian, Geneva and UN conventions and developing professional and social attitudes against war.

[1] The word manmade is purposefully chosen with a male gender bias as wars are typically male projects showing their aggressive, assertive nature while females are more nurturing, tending towards peaceful, negotiated co-existence.

[2] unpublished document of the WHO ICD-11 Working Group on the Classification of Disorders Specifically Associated with Stress

[3]Though the author is a member of the WHO ICD-11 Working Group on the Classification of Disorders Specifically Associated with Stress, reporting to the WHO International Advisory Group for the Revision of ICD-10 Mental and Behavioural Disorders, the views expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and, except as specifically noted, do not represent the official policies or positions of the International Advisory Group or the World Health Organization.

————————————-

Daya Somasundaram is a senior professor of psychiatry at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna, and a consultant psychiatrist working in northern Sri Lanka for over two decades. He has also worked in Cambodia for two years in a community mental health programme with the Transcultural Psychosocial Organisation. Apart from teaching and training a variety of health staff and community-level workers, his research and publications have mainly concentrated on the psychological effects of disasters, both man-made wars and natural tsunami, and the treatment of such effects. His book Scarred Minds: The Psychological Impact of War on Sri Lankan Tamils describes the psychological effects of war on individuals. He has co-authored The Broken Palmyra: The Tamil Crisis in Sri Lanka: An Inside Account.

Somasundaram received the Commonwealth Scholarship in 1988 and the fellowship of the Institute of International Education’s Scholars Rescue Fund in 2006–07. He is a fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists and Sri Lanka College of Psychiatrists. He has functioned as co-chair of the subcommittee on PTSD formed under the WHO working group on stress-related disorders during the ICD-11 revision process. Currently on an extended sabbatical in Australia, he is working as a consultant psychiatrist at Glenside Hospital, supporting Survivors of Torture and Trauma Assistance and Rehabilitation Service (STTARS), and is a clinical associate professor at the University of Adelaide.

Grab a copy from:

http://www.uk.sagepub.com/books/Book241970?subject=K00&classification=%22Academic%20Books%22&sortBy=defaultPubDate%20desc&fs=1

http://www.sagepub.in/books/Book241970?prodTypes=any&imprint=%22SAGE%20India%22&sortBy=defaultPubDate%20desc&fs=1

http://www.amazon.com/Scarred-Communities-Psychosocial-Man-made-Disasters/dp/8132111680

http://www.amazon.com/Scarred-Communities-Psychosocial-Man-made-Disasters/dp/8132111680

http://www.bookadda.com/books/scarred-communities-psychosocial-daya-somasundaram-8132111680-9788132111689

Thank you for article.

Did you know about this accountability in prev regime?

After all this happened, Militarization still ?

End result: worse than PTSD! 🙁

Thank you for your comment. Here is the link to another article – http://liveencounters.net/2015-2/12-december-2015/1-volume-civil-and-human-rights/dr-daya-somasundaram-a-lost-generation-of-tamil-youth/