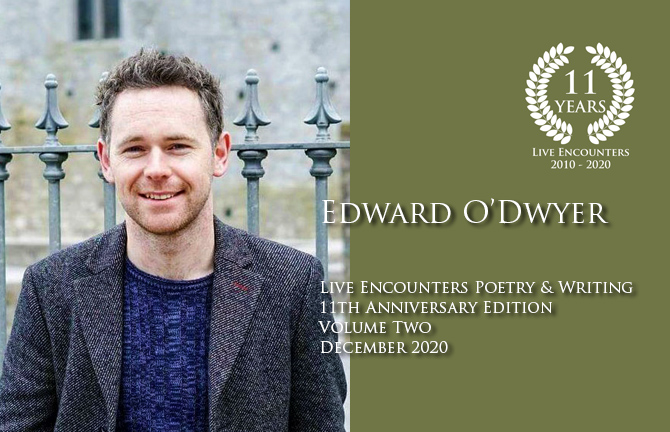

Live Encounters Poetry & Writing, Volume Two, December 2020.

Edward O’Dwyer is from Limerick, Ireland, and writes poetry and fiction. His most recent book, Cheat Sheets, was published by Truth Serum Press (2018) and features on The Lonely Crowd journal’s ‘Best Books of 2018’ list. His third collection of poems from Salmon Poetry is due in 2020, entitled Exquisite Prisons. The collection The Rain on Cruise’s Street (2014) was Highly Commended by the Forward Prizes, while the poem ‘The Whole History of Dancing’, from Bad News, Good News, Bad News (2017), won the Eigse Michael Hartnett Festival 2018 ‘Best Original Poem’ Prize. His story ‘The Man Who Became Poems’ was recently a Finalist in the London Independent Story Prize. He is on Twitter at @EdwardODwyer2

A Short Story

I took to watching her through her windows, just her. I looked in as she performed mundane domestic tasks. There was nothing sexual in it, no, I don’t think so. I mean that, though I’m not saying at all, either, that that sort of thing would be beneath me. I have done and will again do lower, baser things.

She was always fully dressed. It just became a habit. I became an expert, I suppose. I never touched myself or got a hard-on. Like I said, nothing sexual. I was never even aware of any attraction to her. She wasn’t my type, not in the slightest.

It became something to do, another channel to watch. Did I need an explantation for it beyond that? Did I need to call in the Freudians? I was spending less time at bars drinking too much and gawking at pretty bartenders all the while. This, ironically enough, was very much a healthier and less creepy phase in my life.

After some time I upped my intake. The time I spent crouched at her various windows included times when her husband was home, and then those times started to become the times I enjoyed best. Enjoyed has got to be the wrong word here, but you know what I mean. I might watch them eat or argue or watch a movie.

I’d pull my coat around me, shield myself from the winter. The winter was jostling for supremacy at the windows during those days. We co-existed. I guess it was like the winter in any other circumstances. It would always be itself. You couldn’t fault the winter in that sense. It kept its cold, wet promises every time, every time.

One evening, though, through a crack in the curtains, I watched, and something different happened. I was waiting for a scene of some kind, but not a particular one, and not even the typical crack in the curtains sort of scene. I’d never seen them fuck. I genuinely think I’d have left if I’d had a view of that. I think that was a line I was never interested in crossing, not this time.

She tore open the curtains suddenly and we were face to face at last. We were inches apart. I was closer to her than, say, two people having coffee in a cafe with tiny tables. I held my breath instinctively. I thought of running, of course, but instead froze, as though the winter, behind me, had whispered it and I was obeying. She didn’t scream or look horrified, and I knew, looking out into the dark, she saw only the dark and the reflection of herself.

Still, I dared not move. If she could not see me in stillness, the game might yet be up with the slightest movement. She’d call for her husband. He’d spring into action. She’d pick up the phone. The police sirens would close in around me. I don’t need all of that again, especially when I’m not a pervert, not this time.

And so I managed my breath so as not to fog up the glass. Tiny breath followed tiny breath. She folded her arms and looked at the glass and the darkness and herself. She was obviously in no hurry.

I looked into her eyes. I was aware of the fact that people are forever saying there was this or that in somebody’s eyes, sadness or joy or loneliness or anger, but who can ever really tell? I looked into her eyes and I chose not to presume anything of what might be there. I think it’s better that way. They were green, that’s enough to say of them.

After a while her husband appeared in the doorway. He was looking at the back of her head, saying something, but I’m not sure what, and again I’d rather not presume. She didn’t turn around. My feet ached under me as he came closer, but slowly, precisely. He placed a careful hand on her shoulder. She stiffened a little bit but left it there. He was saying something again, and I realised he was apologising.

Marriage is, among other things, I started to think, a series of apologies. It’s like tennis, but with apologies instead of tennis balls. Ideally it finishes as a draw. The umpire calls it a tie.

My own marriage failed because I was never much good at apologies. I was about as good at marriage as I was at tennis. Anyway, that was a long time ago.

I watched his words, whatever they were, coax the stiffness out of her. Her body relinguished its rigidity. She didn’t smile at all but her frown did soften. His apology, whatever it was for, was working. He got closer again, connected his body to hers. He slowly put his arms around her, and clasped his hands together at her chest. She let her weight rest against him.

Together they looked at the glass and the dark and themselves, the tableaux of marriage they were in that moment, as did I, but I was seeing it without the dark. I was seeing it in the pure light. I knew as I watched them there that it was time to go back to the bars, it was time to go back to the life I suppose I always knew I’d have to at some point go back to. It was mine just as surely as this was theirs.

© Edward O’Dwyer