Download PDF Here

Live Encounters Poetry & Writing, Volume One, December 2020.

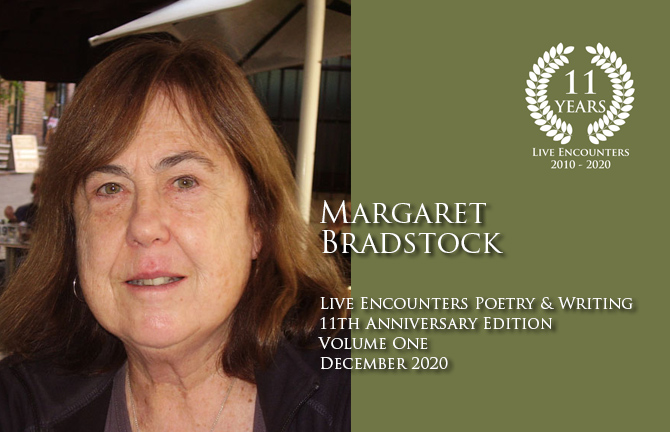

Margaret Bradstock is a Sydney poet, critic and editor. She lectured at UNSW for 25 years and has been Asialink Writer-in-residence at Peking University, co-editor of Five Bells for Poets Union, and on the Board of Directors for Australian Poetry. She has eight published collections of poetry, including The Pomelo Tree (winner of the Wesley Michel Wright Prize) and Barnacle Rock (winner of the Woollahra Festival Award, 2014). Editor of Antipodes, the first Australian anthology of Aboriginal and white responses to “settlement” (2011) and Caring for Country (2017), Margaret won the Banjo Paterson Poetry Award in 2014, 2015 and 2017. Her most recent book is Brief Garden (Puncher & Wattmann, 2019).

Murramarang

Ships first appear like angels’ wings

sprouting from god-like backs, breaking

the plimsoll line of horizon

that divides water from sky, parabolic

dunes from white coastal cliffs.

Natives in rough dugouts

make no move to paddle out, examine

the massive apparition

ploughing through their waters.

A mirage of sunlight

it would disappear.

Near Brush Island, Cook and Banks

attempt to make anchor

the seas too rough, surf

towering like glaciers.

From a distance they (re)name

landmarks: Dromedaries Head, Jervis Bay

the shadowed dome of Pigeon House

chasing the coastline. Smoaks are seen,

at night five fires, the land rather

more populous than first surmised.

*

At Murramarang Point

the complex of 12,000 year old middens

stretches through history

meeting place for Wandandian

and Walbanga tribes

the headland a burial ground

for massacres by local pastoralists,

ancestral skeletons eroded

out of sand deposits.

Shells, bone tools, millions

of stone artefacts the vestiges.

A small, brackish lagoon to the north

an unidentified waterhole

are home to a Dreamtime serpent,

habitat of swamp oak and paperbark.

Black swans, little pied cormorants

and white-faced herons nest here;

sand mining and vehicle access

deep wheel ruts and erosion

scars across the country.

*

All Cook saw was a primitive

aimless culture

naked bodies painted with

broad white stripes

slow wing-beats of a swan in curving flight

over the lagoon, a continuous series

of sand dunes and a land

inhabited by no one.

Trim (1799-1804)

One of the finest animals I ever saw….his robe a clear jet black,

with the exception of his four feet, which seemed to have been

dropped in snow….also a white star on his breast.

− Matthew Flinders

Born on board Reliance, in the Southern

Indian Ocean, he took the captain’s eye,

the cat who walked by himself,

named for Tristram Shandy’s butler

but trim, like his master, or the sails

on a seaworthy ship, adjusted to suit the wind.

Falling overboard, he swam after the boat

scaling the ropes to safety, bravery rewarded

by a seat at Flinders’ table (sometimes swiping

tidbits from the forks of others).

Foregoing feline pursuits, he became a seasoned sailor

first mate and kindred spirit to the reckless,

star-crossed, and sometimes disagreeable captain:

My faithful intelligent Trim! The sporting, affectionate

and useful companion of my voyages.

from The Explorers’ Tree

If there really exists within our great continent a Sahara…great lakes…

or watered plains which might tempt men to build new cities, let us know

the character and promise of the land…” – Rev. John Storie, August 1860.

King:

A rousing farewell at Royal Park

we set off proudly for the Gulf country,

fourteen men, twenty-five camels, horses

and twenty tons of baggage,

aiming to fill in the great blank in the map

the ragged emptiness

like a hole in the night sky.

The camels gave us trouble from the beginning.

The horses cannot stand the smell of them

so our party advances in two straight lines,

Burke riding down the middle, his pistol cocked.

At the Darling River he disagrees

with second-in-command, George Landells

giving rum to the camels to calm them.

A shouting-match ensues, Burke smashes

every bottle of rum, Landells resigns

and Wills is promoted. They might have done well

to have drunk the rum. At base-camp Menindee

travelling now into the hot and dry interior

Burke quarrels with surgeon Herman Beckler.

By Cooper’s Creek, we’re down to four men, six camels,

dump much of our swag, for a mad dash to the Gulf.

A hard, slow slog through soft and rotten country,

sandy and stony in turns, arid scrub, occasional water-holes,

sparse pasture. Not even the triumph of reaching the sea,

only a tidal channel amid the mangrove swamps.

The return journey no better, severe storms, ground so boggy

the camels cannot walk on it, the torpor of stifling air.

Burke catches Gray eating stolen floury gruel

and thrashes him. He shoots the camel Boocha

then later his own horse Billy, and we eat our fill

as much as our stomachs can hold. Falling behind,

now tied to his camel’s saddle, in the trek

across Sturt’s Stony Desert under a blazing sun,

Gray dies. We scratch out a shallow grave and stagger

into an empty camp, the depot party gone.

William Wills:

Our deaths will rather be the result of mismanagement

of others, than of any rash acts of our own.

Coopers Creek, June 1861

And so we come to our explorers’ tree

the “dig” tree left by Brahe, a blaze on the trunk

a small supply of food, and the pleasing information

of their departure. What were they thinking of?

Encouraged by the sound of crows ahead,

the sight and smell of smoke, we start for

the blacks’ camp, thinking to live with them

learn their ways and manners, but they’ve moved on.

Reduced to starvation now on nardoo cake,

by no means unpleasant, but for the weakness felt,

I sense the darkness tumbling in…the silence of letting go.

Near daybreak, King sees a moon in the east, a haze

of light stretching up from it, declares it to be

quite as large as our own moon, and not dim at the edges.

I am so weak that any attempt to get a sight of it

was out of the question; but I think it must have been

Venus in the zodiacal light….

Nardoo is no fit food for white men.

Melting

In the city, in springtime, Anna steps out into drifts of hail the size of boulders, into floods and gale-force winds, and thinks of billions of tons of ice, flowing faster than snowfall replenishes. An iceberg breaks off from Ross ice shelf, and the Bay of Whales ceases to exist. Ice that trapped Shackleton and crushed his ship, the floes that proved impassable all melting now, faster and faster, locked into a process already begun. An extra five metres added to sea levels will mean submerged buildings and motorways, the coastline another Atlantis. Shackleton gave Frank Hurley his mittens, suffering frostbite himself, so the photographer could walk out into his frozen image, as though part of some vanishing point in another century.

Burning fossil fuels have already melted the first two sections of the Larsen ice shelf. Now the third and most massive section, an iceberg twice the size of Samoa, calves off into the South Atlantic Ocean, shatters like safety glass. A century ago Carl Larsen, master of the Norwegian whaler Jason, sailed past that sculpted ice front from Cape Longing to Heard Island, stunned by its fringing bays. Anna decides she must see glaciers, before they all vanish.

She leaves on a cruise ship for Alaska, aware of the many differences between her journey and those others. Winter is rising, but the peaks of distant mountains are barely touched with white. On the eighth day the ship approaches Hubbard Glacier which surges towards the gulf, blue beneath the waterline and just above it. Ice blue as blown glass or ammonite shell calves off like bubble-foam. Anna hears the glacier split, broken floes drifting by the boat, imagines a migration of fish, birds, mammals. When they dock at Ketchikan, she will buy a piece of ammonite shell as a memento.

On a rocky island nearby, sea-lions stretch out in the sun, as the world that survives grows smaller.

© Margaret Bradstock