Funeral Sentences, Guest Editorial by Christopher Merrill

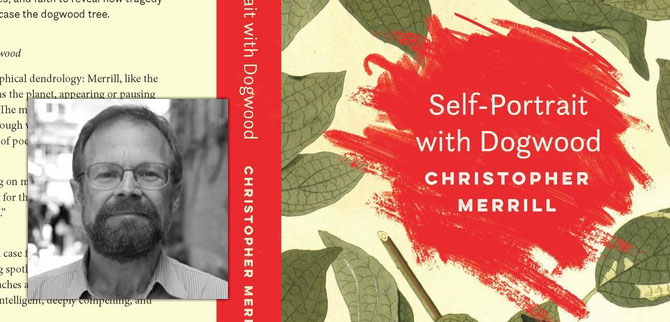

Christopher Merrill has published six collections of poetry, including Watch Fire, for which he received the Lavan Younger Poets Award from the Academy of American Poets; many edited volumes and translations; and six books of nonfiction, among them, Only the Nails Remain: Scenes from the Balkan Wars, Things of the Hidden God: Journey to the Holy Mountain, The Tree of the Doves: Ceremony, Expedition, War, and Self-Portrait with Dogwood. His writings have been translated into nearly forty languages; his journalism appears widely; his honors include a Chevalier from the French government in the Order of Arts and Letters. As director of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa, Merrill has conducted cultural diplomacy missions to more than fifty countries. He serves on the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO, and in April 2012 President Obama appointed him to the National Council on the Humanities. His website is: www.christophermerrillbooks.com

The graffiti on the wall of an apartment building in Skopje pleased the poets on their way to the Struga Poetry Evenings in North Macedonia: MORE POETRY IS NEEDED. In the van were poets from India, Iran, Israel, Kosovo, Mongolia, Spain, and other countries, and on the drive through a wide valley between two mountain ranges I supposed the scrawled words had different meanings for each of us. Lake Ohrid was our destination, a place I had first visited as a journalist in the winter of 1992, during the wars of succession in the former Yugoslavia, and now on a hot August morning we passed vineyards and cornfields, houses with red-tiled roofs and a fire-scarred hill. In a summer marked by mass shootings, immigration raids, protests in Hong Kong, tensions rising in the Persian Gulf, a trade war with China, incontrovertible evidence of climate change, and increasingly unhinged tweets, pronouncements, and bald-faced lies from Donald Trump, I found some consolation in Geoffrey Hill’s posthumous volume of poems, The Book of Baruch by the Gnostic Justin. The witness of poetry, Hill reminds us, can be redemptive, even or especially in difficult circumstances. For his determination to interrogate every aspect of his walk in the sun is by turns exhilarating and bracing: he stared into the abyss throughout his long career, and what he discovered there, translating into some of the most vital poetry of our time, may be useful for those of us who wonder how to make sense of the crises we now face.

One night in Portland, Oregon, between reporting trips on the siege of Sarajevo, I had the good fortune to see Hill read with Donald Hall. This was near the beginning of what would be a remarkable run for a poet heretofore known for his scrupulous, if meager, output. Hill later credited “the taking up of serotonin” to treat chronic depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder for his newfound productivity; between 1996 and his death in 2016 he would publish nearly 800 pages of new poems, four times as many as had appeared in print during the first four decades of his writing life. On that evening in Portland, though, he still had the air of a convalescent, and I was struck by Donald Hall’s decision to make his friend the centerpiece of the event. He recalled his excitement upon discovering and then publishing Hill’s poetry when they were students at Oxford, and now I recalled his generosity on stage toward a man whose pain was so clearly etched in his face. It was, I decided, the best attitude to adopt at the outset of a poetry festival.

Hill’s poems, which are often judged to be difficult and allusive, sound every conceivable note and tone in a register whose contours seem to widen line by line. “If testimony is of a witness,” he asks toward the end of The Book of Baruch by the Gnostic Justin, “how should I summon or speak for myself?”—a question every poet must answer. Hill’s answers in this last poetic will and testiment, the various selves he presents in a sequence of some 271 poems, take different forms—prophesy, curse, wisdom literature, joke, lyric—all marked by this stark recognition: “So short the time while the lime leaves have become darker and denser.” This may explain his interest in Henry Purcell’s “Funeral Sentences,” which helped to define the end of one political order and the advent of another: “Take heart, the Funeral Sentences are neither an act of homage nor a bill for damage.” I suspect The Book of Baruch by the Gnostic Justin will play a similar role in our time.

Hill died one week after his countrymen voted to leave the European Union. If he had once described the 1992 Maastricht Treaty as “an international corporate fraud,” the verdict he delivers in his short final poem reveals that he had revised that opinion, because he recognized the danger posed by the rise of populist anger to the civilizational values and ideals he had always cherished. He seemed to foresee how this would fuel anxiety everywhere:

The numbness after the shock of exit, big-bummed Britannia in her tracksuit;

her phantom lap of honour; no other runner.

July the dark month; the lime leaves turned matt. The newly-bloomed mallow

will see us re-autumned before it falls fallow.

Even so, the power of stout roses has risen watt by watt against the afterglow of

each brief thunder-shower.

Brexit was, of course, the most visible sign that something had gone awry in the western political order before Donald Trump was elected president later that fall. Coincidentally, the 2019 Struga Poetry Evenings coincided with the annual G7 summit in Biarritz, France, which the leaders of the world’s largest economies feared Trump would disrupt, and as I listened to the poets recite their poems in their different languages, reading along in English translation, I concluded that they were expressing “the power of stout roses [rising] watt by watt against the afterglow” of what was turning into a global thunderstorm, which had the potential to destroy everything. Which is to say: they were composing Funeral Sentences for an unsustainable way of being in the world.

The Romanian poet Ana Blandiana was awarded this year’s Golden Wreath at the Struga Poetry Evenings, celebrated for her powerful poetic voice and as “a symbol of rebellion… against Ceausescu’s totalitarianism.” In a press conference at the Hotel Drim she ascribed her dissent from the Communist order to her childhood in Transylvania, which had a tradition of rebelling against Hungarian invaders; her political poems, she explained, mirrored her countrymen’s state of mind and the dreariness of daily life in Romania: “We live in a wound,” she wrote; “the only certain thing is the pain that surrounds us.” No wonder she ran afoul of the authorities. “I was banned, even before I became a poet,” she said in another poem, which circulated in samizdat editions—a practice came to an end with the fall of the Ceausescu regime, when she found a new poetic destiny. She wrote: “The only that changed after 1989 is that I am no longer afraid.” Yet she feels more at home abroad than in Romania, where poetry had lost its central place in the culture.

“In Romania,” she explained, “we often discussed the subject of resistance through culture. We survived Ceausescu through this resistance. But resistance is more important now than before, because culture is being replaced by anti-culture. The fact that it is normal to talk about the end of Europe is proof that culture doesn’t represent anything anymore, even in Europe. Europe created two totalitarian societies, two world wars, and yet poets continued to write. We must create a movement of intellectual solidarity to counter the media’s destruction of culture.” In her poem “Biography” she wrote: “Every poem unsaid, every word not found,/ Threatens the atmosphere.” After the press conference I headed for the lake to find these words.

© Christopher Merrill