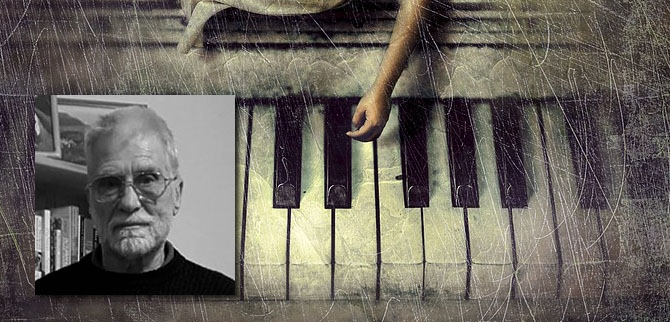

Lost Language of Trains, poems by Ian C Smith

Ian C Smith’s work has appeared in, Amsterdam Quarterly, Australian Poetry Journal, Critical Survey, Live Encounters, Poetry New Zealand, Southerly, & Two-Thirds North. His seventh book is wonder sadness madness joy, Ginninderra (Port Adelaide). He writes in the Gippsland Lakes area of Victoria, and on Flinders Island, Tasmania.

Binoculars

His birthday present from her to fill in nights when he couldn’t get started prompted a memory of him saying what you see in reality differs from the movies, no dual arcs. He called movie-makers sly tricksters, yet he deceived readers, liked a joke despite what he wrote, aimed them, looking up on a clear night, to claim he caught the man in the moon picking his nose. They lived in a cold climate those days, above the bike repair shop, his part-time work paying peanuts. Traffic’s background hum accentuated loneliness, he said, and poverty, trundling a battered Portagas heater room to icy room, castors squeaking, veering an erratic course like a supermarket trolley. He pressed a plunger until it ignited emitting a smell of burnt dust, then turned off the lights to save money, really for atmosphere, sat in an armchair overlooking the street, those windows the only ones kept clean. She grew accustomed to sudden pops of cheap champagne’s corks detonating the dark, his bottle balanced on the heater with an ashtray, reflections of the shop fronts’ fluorescence gleaming off binoculars trained on the night parade he called ‘the market’, inventing dialogue he ‘saw’, strangers’ puffs of soggy breath like cartoon bubbles. If magnified unsuspecting characters, a jogger, couples, cops, a busker, belligerents in a fracas, stepped within range, faces haloed by neon, he snared them, triggering a dramatic scene, the story in his head matching near silent action. He believed champagne helped control his drinking, sipping quickly, binoculars heavy to hold one-handed. She paid a lot for them, resented people asking, wanting stories of human weakness to always be hers and his, expecting them to be scriptural. She disappointed, saying some published writers are boring fantasists to live with, and make little money.

Drinking

My son asks me, an abstainer now, to drive him to his suit fitting, flying from interstate where he finally landed a steady job, to attend a bucks’ party, and be measured up for when he stands as best man. Now I live alone, I don’t see him much since he lost his licence wrecking his car, breaking his brother’s ankle.

The day I suited up as best man, a humming Melbourne morning in my grim youth, escorting the maid of honour whose husband, a leading jockey, rode a winner at a rural track while we celebrated the marriage of my friend who had arranged our small bridal party to spend that evening drinking together, enjoying being young at his mother’s empty house, the clock hands were circling. Leaving the sanctuary we processed through dust motes towards sunlit open doors, and thunderbolt news. The jockey had visited a bar with other riders before setting off to drive to the city. Soon after, he ran down, and killed, a pedestrian.

I have traced people from long ago as far back as my first best friend at school, including those I gave little thought to, life wildly galloping by, but found nothing of that jockey’s uncommon surname and distinctive nickname. Old newspapers digitalized, this racetrack hero’s feats, his serious traffic offence, seem to have evaded cyberspace.

That flattened post-wedding party broke apart, marriages, friendships, those events, the aftermath, forgotten. Now, the music we played golden oldies, memory a Rorschach test of blurred imagery and blanks, I wonder what happened after that jockey’s terrible blunder, happiness muted, his wife’s gut gripped by horror. I imagine my son, much older, wiser, gazing at photographs straining to recall past events some future day, hope these won’t include trauma, celebration crumpling into tragedy.

Lost Language of Trains

An early scene from My Beautiful Laundrette. South London, where my father grew up. Daniel Day-Lewis a gay bovver boy, no way of knowing he shall one day be the U.S. President, still young then, as was I. Trains racket along the line below a young Pakistani Englishman whose mother suicided by jumping onto it, where he pegs laundry that will fleck with soot, take forever to dry, as it does in rain-streaked districts of stained bricks.

I became familiar with laundrettes in Thatcherite London, and constant trains, their echoes wails of suffering as if from ancient bones buried beneath the lines in that centuries-old city of conflict. Like a pardoned convict’s return, mine took years from when my parents whisked me to the other end of the Earth if that verb is applicable to a crude six-week voyage by ex-troopship after we seemed to leave as hurriedly as the squatters scrambling out the window in another early scene.

One woeful Wednesday, sent home from school because the King died, I skipped home joyous at this unexpected half-holiday only to disturb my mother, a chilblained war-damaged woman, hands fixed in washing-up water, staring at something nobody else saw, face damp with sorrow. Soon we were off, to the Australian jungle, I thought. Well, school was savage, which suited me, London days disappearing dreamlike.

Back Down Under where laundry dries quicker than yesterday dies, a squatter myself wherever I lived, years worn to the bone now, the evening train comes on down the line, earworming me, a train in an Elvis song, lights semaphoring my walls, hauling me back to when everybody seemed on the dole, another line from that film, when I needed little more sustenance than the energy, the wan thrill of returning emigres you could call underground love, memory and landscape alike in attrition.

That Buzz of Interest

Before mobile phones, noisily busy in the next room, I once heard the staccato of a long message being left on my answering machine. When I had time to play it, it had vanished, to my utter horror, due to a fault in the connection. I never found out who believed I received it, then failed to respond.

Reading Eligible, Curtis Sittenfeld’s clever take on Pride and Prejudice, reminds me how much art makes of mixed or lost messages lit by hope or darkened by despair, the giddiness of thin secrets. Think of Tess of the D’Urbervilles, or other memorable examples, not the Dirty Realists.

Long ago, before words, said and unsaid, proved a formula for my unhappiness, I returned from travels to discover a letter under an antimacassar on my armchair, left – hidden, then forgotten? I shall never know – by either my house-sitter or, probably, his girlfriend. A lovelorn paean, this was written to her, but not by him. Of course, I read and reread it, buzzing with interest. It was better than TV. If Jane Austen were alive she would pillory TV, a la Sittenfeld.

An editor who rejects my submission emails the next day, explaining he had previously published this attached work which did not match the titles in my cover letter. A buzz of interest stirs. Because he reads submissions blind, he thinks his admin error is responsible so invites me to resubmit, albeit not blind.

The following day, after I discover the error was mine, he accepts my new work, as well as what he believes is something else by me he previously rejected. This work is not mine. So we email awkwardly back and forth. Confusion. Misunderstandings. Happiness. Despair. Even a misread tone can alter the course of lives according to certain novelists. And so the heart rises and falls as we dance the tightrope of language. At least I am not in love, wish I were intriguingly so.

© Ian C Smith