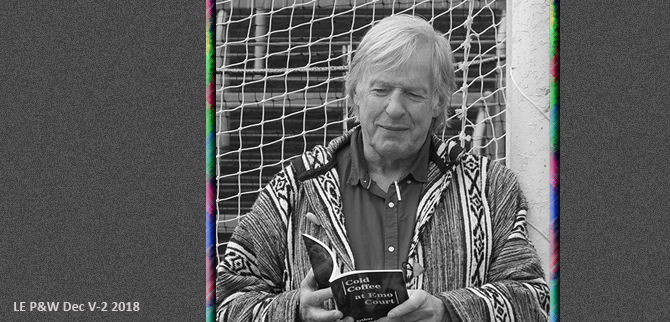

The Lifeguard, short short story by Arthur Broomfield

Dr Arthur Broomfield is a Beckett scholar, poet and short story writer. His works, which include a study on the works of Samuel Beckett and two poetry collections have been published by Cambridge Scholars’ publishing, Lapwing and Revival Press. His next collection of poetry will be published in April 2019. His poems have been published in US, British, Indian and Irish journals. Arthur lives, with his wife Assumpta, in Ballyfin, County Laois, Ireland.

Arthur Broomfield wishes to acknowledge Greta Stoddart’s poem Lifeguard [from her collection Alive Alive O, Bloodaxe] as the inspiration for his short story.

The car radio was blasting out the lines of “I’m not that kind of girl”, a library copy of August is a Wicked Month kept time with my driving as it slid back and forth across the dash. My three under tens were squabbling over who had the best swimwear as I pulled in to the Portlaoise Leisure centre. I had promised my all girl brood we’d join once school holidays had begun. “I want to swim like you Mummy,” Matilda, said, after watching me do my twenty lengths of front crawl the day Jack and I sussed out the pool, bringing her along to approve, she being the eldest. So today was the O’Connor family’s, minus husband, first full working visit to the centre. In a way I was glad he wasn’t with us. Jack would fuss over the creases in his Austin Reed suits, when his shirts lost the pristine feel of the moment of their first wearing they were sent to Oxfam. I could imagine him: “Matilda keep close to Eliza…don’t go near the deep end…are you sure your hair’s dry? “

The car radio was blasting out the lines of “I’m not that kind of girl”, a library copy of August is a Wicked Month kept time with my driving as it slid back and forth across the dash. My three under tens were squabbling over who had the best swimwear as I pulled in to the Portlaoise Leisure centre. I had promised my all girl brood we’d join once school holidays had begun. “I want to swim like you Mummy,” Matilda, said, after watching me do my twenty lengths of front crawl the day Jack and I sussed out the pool, bringing her along to approve, she being the eldest. So today was the O’Connor family’s, minus husband, first full working visit to the centre. In a way I was glad he wasn’t with us. Jack would fuss over the creases in his Austin Reed suits, when his shirts lost the pristine feel of the moment of their first wearing they were sent to Oxfam. I could imagine him: “Matilda keep close to Eliza…don’t go near the deep end…are you sure your hair’s dry? “

I shouldn’t complain, he’s the husband women dream of. My boast “I’ll do it love, you’ve enough to do looking after the girls”, when he saw me getting out the hoover on Saturday, fell on curious ears at last week’s coffee and chat in Costa.

“But sometimes … I know I sound wicked, but sometimes I wish he wasn’t so good,” I added.

“Your Jack is the gentle type Joan, maybe he’s got you spoiled. There are times when a woman can need …well, something more.” Susan gripped my arm and looked deep into my eyes.

The chat drifted from families – “Albert’s going into first year in September,” Greta told us – to the quality of the coffee.

“I like the cappuccino here, you’re always sure of a good creamy head,” said Susan.

“I’m off now girls, it’s time for my swim. “

Greta gathered her bags and said her goodbyes.

‘What’s the big smirk about Susan, “I said?

“Maybe you should take up swimming again, Joan.” Susan fixed her silent gaze on me again.

Susan’s look drifted across my mind when I saw him first, a butty, muscly thirty-five-year-old, or so, slumped in the deck chair that goes with the lifeguard’s job, positioned behind yesterday’s “Star”. Wanting to set an example in good manners to the girls, I projected a “good afternoon” in his general direction. “The Star” lowered, to reveal a close cropped, reddish root haircut, ears pierced and bejewelled with an assortment of hoops and studs. Among multiple tattoos disfiguring arms exposed by his gym bunny’s muscle vest, and doing nothing to enhance his short neck, the usual “Mum” “Dad” and designs representing God knows what, I noticed an incongruous red rose. Without raising his eyes he acknowledged my greeting with a shift on the deckchair and a barely audible grunt.

“That man at the pool looks like ‘Pinhead,’” Matilda said, as we drove home.

“Don’t be silly Matilda, just because he’s not like your Daddy doesn’t mean he’s not a good man. Men like him are trained to do things your Daddy doesn’t do.”

“But he’s cross Mummy and he was rude to you.”

“He can save lives love; maybe we’ll need him one day.”

I made a point of bringing the girls to the pool three times a week. After five or six trips, once I was confident they’d be safe in the kiddies’ pool, I got back to swimming myself. I’d been a good swimmer in college, winning an inter-varsity championship in the 200-metre freestyle in my final year. The pure pleasure of sensing the water caress my body as I seemed to glide fluently from end to end brought back memories of my best days.

The Lifeguard, as he was known to us, continued to be an inscrutable presence, employed, I thought, to represent the cold face of Laois County Council. If I’d ever wanted to pass myself with him I couldn’t imagine an opportunity presenting itself. On the rare times when he absented himself from the deckchair he could be seen standing, his head resting on his folded arms now astride the wide head of an upturned brush, gazing passively towards one end of the pool, into a distance he seemed to be contemplating. Viewed from the water his tank like torso was a twenty first century caricature of the David sculpture I’d drooled over in Florence; it seemed to draw its inspiration from testosterone fuelled Olympic weight lifters rather than the mythical Gods of Mount Olympus. Not wanting him to notice me – after my first putdown I made no further attempt to communicate with him – I switched to the breast stroke to make full use of the blindside half-length of pool from where I could study him from the back. A woman will be drawn to that which attracts her despite logic or reason. The glistening skin on his upper arms was pulled taut as it struggled to contain his exaggerated bi- and triceps. I trod water and gazed upward at his neck from five or six yards. Thick and short it was almost as wide as the unremarkable melon that sat on it. A double row of muscly ridges, separated by a perspiration-soaked channel, brought the term ‘bull-neck’ to my mind. Seeing his body stiffen I sensed he was about to turn so I resumed my front crawl, keeping my thoughts to myself.

So, the weeks went by. My swimming was getting back to college days standards, I was enjoying myself so much I tried to make the pool every possible day.

“I wonder should I enter for the gala,” I asked Matilda, after a good session, “did you see the poster, it’s on in three weeks?”

“Oh do! do! Mummy. I bet you’ll win it!”

“Well, maybe, but I’d better get new swimwear.”

“You’d swim even faster in a bikini Mummy,” Matilda’s eyes sparkled with pride.

———

“Yes, we do stock that particular type of swimwear.”

Miss Halmesworth scrutinized me through spectacles secured in sturdy, russet frames that seemed conjoined to hair that was swept to a hairpin indemnified, oven ready bun.

I’d chosen Halmesworth’s for privacy, rather than Tesco where a plentiful selection of bikinis would be in stock but in full view of whoever might decide to stroll through the lingerie rails on the way to the fruit and veg department.

“We may not have your… colour at the moment.”

“Well let’s see what you’ve got.”

Miss Halmesworth walked half-way down the counter and reached for a short ladder that rested against a pile of blue boxes. She dragged it, simultaneously discharging deep breaths and audible sighs, to the farthest end, where, after a focused pause, she laid it against a shelf of green boxes. She reached up from the third step and pulled out one from among the pile. It had a picture of a model lounging under a palm tree, which she eventually laid on the counter in front of me.

“We may have something to suit you here. These are the type they’re wearing nowadays”, she nodded towards picture on the box.

“I quite fancy this one,” I held up the briefs of one with a post-modern flower pattern.

“It’s in animal print,” she said solemnly.

“Yes, I’ll take it.”

It was around seven o’clock on an early August evening, when I saw him uprooted from his limited repertoire of positions in the pool, outside a humble house that I presumed to be his parents, on the Ridge road. He was pulling on a crash helmet, fastening it round the ears as he mounted what looked like a powerful motor bike, a Honda, maybe, I wouldn’t know about these things. He cut out in front of me; stretched out along the bike his body had taken a different shape to the clumsy hulk I had become accustomed to meeting at the pool; more elongated, back arched, sun glistening on his shoulders, he sped away from me. My chat with Susan in Costa seemed to grip me. God, I thought, where have I got myself?

“Mummy, Mummy” Matilda was screaming as I finished my tenth length, “the lady is drowning, quick quick.”

She grasped my hand and dragged me from the water, pointing towards the far end, still shouting. I slithered along the tiles with all the grace of a novice skater’s first day on ice, relying on Matilda to hold me up. Conscious of my bouncing boobs but not caring how I appeared I tried to focus on the huddle gathered on the end edge of the pool. A stoutish woman lay stretched, motionless, across the tiles. Over her, stripped to his trunks, the lifeguard was directing sharp downward blows to her chest. After a succession of maybe four or five blows squirts of water shot from the woman’s mouth. He rolled her over on her side and continued the process, now applying it to her back. Again, he rolled her onto her back.

“Will you all stand back, “he commanded the curious throng. Weak cries broke the silence as he continued to pummel her chest. “We’ll lose her” a voice bleated. A glare from The Lifeguard silenced the doubting Thomas. He cupped her head firmly with both hands, one beneath her chin, the other holding her pole in place. Next, he reached over her and bending down felt for her lips till his lips matched them. Now that no air could escape he blew firmly into her mouth, withdrew, and repeated the exercise four or five times, each time with increasing confidence. His lips seemed to find hers with growing familiarity, caressing them back towards consciousness with each kiss. A tingle, then a shudder then uncontrollable trembling followed by cries of pain or relief told us that the woman was saved.

I bought a sturdy envelope, the kind that has bubbly underlay and can be firmly secured, and a red rose. An altar of sorts stood in the entrance to the pool with a photograph of him on the motor bike that had caused his end to one side, a bunch of white lilies to the other. People were coming and going saying I never got to know him, and I’d better go to the funeral anyway. I went into the ladies and slipped off my panties. I sealed them into the envelope and walked back to the altar as nonchalantly as it’s possible to be at such a moment. I laid the envelope in the middle of the table and placed the red rose on top.

© Arthur Broomfield