Guest Editorial: Why men should study women’s poetry by Thomas McCarthy

Guest Editorial: Why men should study women’s poetry by Thomas McCarthy

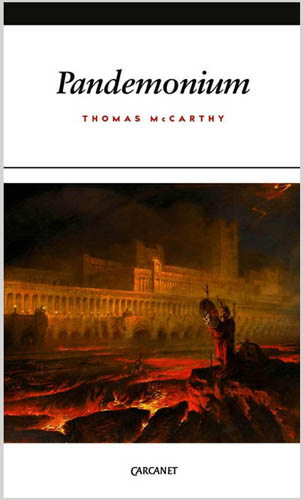

Thomas McCarthy was born at Cappoquin, Co. Waterford in 1954 and educated locally and at University College Cork. He was an Honorary Fellow of the International Writing programme, University of Iowa in 1978/79. He has published The First Convention (1978), The Lost Province (1996), Merchant Prince (2005) and The Last Geraldine Officer (2009) as well as a number of other collections. He has also published two novels and a memoir. He has won the Patrick Kavanagh Award, the Alice Hunt Bartlett Prize and the O’Shaughnessy Prize for Poetry as well as the Ireland Funds Annual Literary Award. He worked for many years at Cork City Libraries, retiring in 2014 to write fulltime. He was Humphrey Professor of English at Macalester College, Minnesota, in 1994/95. He is a former Editor of Poetry Ireland Review and The Cork Review. He has also conducted poetry workshops at Listowel Writers’ Week, Molly Keane House, Arvon Foundation and Portlaoise Prison (Provisional IRA Wing). He is a member of Aosdana. ‘His last collection Pandemonium was published by Carcanet Press in November, 2016. His new work, Prophecy, will be published by Carcanet in April, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas McCarthy (poet)

A few days ago I gave a talk on Irish Women’s Poetry to a very disciplined and intellectual audience at the ACIS (American Conference in Irish Studies), Mid-West region, at the University of St. Thomas’s Minneapolis downtown campus. Before me were more professors assembled than I’d ever seen in my life. OK, I admit, I’ve lived an isolated life: thirty-seven years in a public library, and the last five years alone in my garden shed, thinking of illness and recovery and writing poems about the way things change for us as we grow wiser. Because I’ve spoken to so few people since I retired (to write full-time) my physical voice has weakened: it is an effort to project it. Like a Cistercian monk from Mount Melleray Abbey, I speak more quietly than I’ve ever spoken and my seeming lack of effort must annoy energetic and serious young professors. But at this stage in my life as a poet I’ve lost the ambition to harangue people into a different point of view, I’ve become less and less interested in rhetoric. Poetry alone is my thing, my companion; its quiet certainties, its holistic inclusions, its luminous remnants of our common humanity.

When I was in my early twenties poetry had an extraordinary physical sweetness. It was like sugar hardened or honey solidified into flaky whitish wafers on the printed page. Its sweetness has come back to me in recent years. I am now more conscious than ever of its private power, its hoarded treasuries, and this consciousness has made me even quieter. But I love breaking off bits of this rich coagulant and sharing the pleasure of poems read slowly. There is a huge connection between slow reading and good writing, and poetry-workshops lie in this creative hinterland, this hinterland where poems get written. I trust poetry workshops more than any other activity in poetry, more than lectures, more than readings, more than performance. At a workshop where the facilitator has created a trusting-space, new poets speak to us without fear of bullying, and with the certainty of a hearing. In such a space we hear the full, welcomed voice of the poem’s maker.

The certainty of a hearing. When did women poets first achieve this certainty of a hearing in the world of poetry? It was in answering this question, but in this quiet mood, that I spoke about Irish Women’s Poetry to the Mid-Western professors, about a poetry that begins in the modern era for me with Máire Mhac an tSaoi’s wonderful ‘Cré na Mná Tí’ or ‘Housewife’s Creed’:

‘You’d expect the bright household

and the family disciplined,

washing, scrubbing, cleaning,

meals arranged and milking,

mattress turned and carpet beaten –

but, in the manner of Scheherazade,

you must, in fairness, accept my poems.’

Or, from the same great poet of the Gael, more daring, more personal, more sexual, the great poem ‘Ceathrúintí Mháire Ní Ógáin:’

‘I care little for the outrage of people,

the disapproval of priests,

for anything except to be stretched

between you and the wall –

indifferent to the night’s cold,

to the lash, the lash of rain,

I lie in our narrow, secretive world

Within the confines of our bed.’

This was our great poet, one of the greatest Irish poets of the last two centuries, mapping a private world in the fearsome cold of the 1950s. As that decade went on, the passions of women were invisible. Women were love-objects, not lovers – indeed, the male poets and novelists turned women of passion into lunatics or objects of derision. Novelist Brian Moore gave us The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearn while Austin Clarke gave us ‘Martha Blake.’ Men appropriated the private life of women in an act of breath-taking presumption. Novelists such as Honor Tracy and Edna O’Brien would defy this male hegemony in their writings, but the poets fell silent, until, one day in early 1980, young woman returned to Ireland from her home in Anatolia, a woman who would transform and enchant the 1980s in Ireland with beautiful, flamboyant, radiant poetry in the Irish language:

‘I place my hope on water

in this little boat of language

the way a mother might place

her little infant

in a basket woven of

iris leaves all intertwined,

its base water-proofed

with pitch and bitumen,

setting the whole of her world

among sedge and bulrushes…..’

The above small poem, ‘Ceist an Teangean’ (‘The Language Issue’) by the young Nuala Ní Dhómhnaill created comment and commentary everywhere in Ireland, dealing, as it seemed, with the burning issue of the Irish language in an increasingly Anglophone world. Now we can re-read this text in a different context – perhaps it is about an even deeper issue, the issue of woman’s voice and sensibility, placed tentatively in the woven basket of a woman’s poem. Like Máire Mhac an tSaoí before her, Ní Dhomhnaill is a creature of passion and assertive yearning. Her breath-taking poem ‘Maidin sa Domhain Toir’ (‘Morning in the Eastern World’ or ‘Oriental Morning’) is one of the greatest personal poems ever written in the Gaelic language, possibly the greatest Irish poem since Yeats’ ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ –

‘Ní foláir ag teacht tar an saol so

go rabhas róchraosach: gur roghnaíos

an bhullóg mhór is mallacht mo mháthair

in ionad na bullóige is a beannacht…..’

‘There’s no doubt in coming to this place

I was too ravenous: that I chose

The full loaf (of life) and my mother’s hatred

Instead of a half-loaf and her blessing….’

In this poem the poet has fled abroad with her lover despite every effort from her professional, haut-bourgeois parents – including an attempt to make her a Ward of Court – to prevent her from leaving Ireland. The poem opens at dawn on the plains of Anatolia where the poet has made a new life with her Muslim husband and baby. She thinks of the great founder of Turkish hegemony, Mehmet I, and how in his moment of sorrow he recognises the future flag of his country in the bloody pool of a horse’s hoofmark. She thinks of her own smaller heroisms, of personal exile and motherhood. The poem is magnificent beyond belief, it is a triumph of human will and artistic grandeur. There is no poem like it in the Irish canon. It may never be equalled.

In those same years, those early years of a mean decade, the 1980s, another already respected young poet, Eavan Boland, also stepped forward and declared a new kind of feminist, person-centred, woman-centred poetry in a series of poems with unexpected titles like ‘Menses,’ ‘Anorexic,’ and ‘Mastectomy.’ Boland became an urgent new map-maker, mapping the body that had been excluded from history, from the political masculine history of Ireland. Male critics simply did not know how to cope with such new materials. Her project of re-imagining Ireland was met with silence, cynical commentary, sometimes with open hostility. It would take many years and many books, such as Night Feed (1980), In Her Own Image (1980), The Journey (1987) and Outside History (1990), before Boland’s new perception and sensibility would find purchase in the Irish critical world:

‘I was standing there

at the end of a reading

or at a workshop or whatever,

watching people heading

out into the weather,

only half-wondering

what becomes of words,

the brisk herbs of language,

the fragrances we think we sing,

if anything.’

(‘The Oral Tradition’)

Nuala Ní Dhómhnaill and Eavan Boland were the beginning of that really new wave in Irish women’s poetry. The example they set, the courage with which they began, eviscerated male categories of thinking and circumvented the gate-keepers of the Irish canon. We have had two and a half decades of marvellous writing and publishing by women. The list of names is impressive: Rita Ann Higgins, Aine Ní Glinn, Bríd Ní Mhóráin, Joan McBreen, Mary O’Malley, Moya Cannon, Medbh McGuckian, Sinéad Morrissey, Doireann Ní Gríofa, the astonishing Paula Meehan, the wonderful Eleanor Hooker and Kerry Hardie, the sublime Vona Groarke, the hypnotic Martina Evans, the gifted Enda Wyley and Catherine Phil MacCarthy; all marvellous poets with distinctive and important voices. And there are others, several others. The latest gifted two are a reminder of how the poetry scene has changed. When I was a young student poet in University College Cork the two dominant poets of the campus were John Montague and Seán O Túama; one the great old voice of Ulster, the other the sparkling Gaelic voice of Munster. But recently, very recently, the same University has appointed two new poets, young voices of the South, to lectureships in its English and Irish Departments – the wheel of life has turned and now two young female poets rule the roost in that place. Time, it seems, has begun to sift the canon.

The first of these poets, Leanne O’Sullivan, has already achieved great things in her elaborate and passionate poetry. Her first collection, Waiting for My Clothes (2004) was published when she was just twenty years old. Since then she has published wonderful work in Cailleach: The Hag of Beara (2009) and, more recently, in that beautiful, heart-rending collection A Quarter of An Hour (2018). The latter book is an astonishing poetic diary of the hours, days and months spent waiting at her comatose young husband’s bedside while he recovered from a severe brain infection. The poems are an astonishing record of the power and terror of human attachment:

‘The eyelash that drifted down the broad plane

of your cheekbone comforts me. It is the archer

travelling across the night-sky of your un-

consciousness…..’ (‘Prayer’)

‘Now an old truth rises to its zenith/ in my adult life’ she writes in ‘Oracle;’ and in ‘Note’ she paints a picture of comatose drifting, separation, survival: ‘If we become separated from each other/ this evening try to remember the last time/ you saw me, and go back and wait for me there…’ (‘Note’) In poem after poem, in ‘Tracheotomy,’ ‘Lightning’ and ‘Morning Poem’ and many others, she creates an astonishing picture of that pain of human attachment, such a picture that places her achievement in the tradition of the great Irish Lament, the County Cork tradition of poems such as ‘The Lament for Art O’Leary’ by Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill: ‘Mo ghrá go daingean tú/ Lá dá bhfaca thu/ ag ceann tí an mhargaidh.’ The power of a wife’s attachment; the passionate, possessive nature of such love is wonderfully expressed by O’Sullivan in A Quarter of an Hour.

The other, equally marvellous, young female poet who graces UCC’s thriving campus is the Irish language poet, Ailbhe Ní Ghearbhuigh. She is a native of Tralee, Co. Kerry, now living in the Lough neighbourhood of Cork (a neighbourhood that feature in the novel The Threshold of Quiet by the legendary Daniel Corkery) with her husband, the poet Billy Ramsell. Energetic, mischievous, provocative and witty, Ní Ghearbhuigh has recently published a selection of her original and translated work, The Coast Road, with Ireland’s premier poetry publisher, Gallery Books. The book brings to a wider, English-speaking audience the confirmed achievement of her two collections in the Gaelic language Péacadh (2008) and Tost agus Allager (2016). Here is a poetry of lust, loss, travel, folklore and philosophy:

‘Tógtar túr eile!

Túr na himní

Tuar an uafáis

Túr na tarcaisne

Tuar na tubaiste.’

(Let’s build another tower!

Tower of anxiety

Omen of horror

The tower of insult

Omen of disaster

Trans: Peter Sirr)

A poet of sure, confident feeling, a poet with the easy familiarity of love and love of the familiar and familial, Ní Ghearbhuigh has created a distinctive, thoughtful new style inside the Irish language. Her work is beyond politics, it is the voice of an entirely new generation, a new sensibility that’s sociable and unshackled from Irish conventions and worries. The delight in her voice within the Irish language is unmistakable. Her youthful confidence remoulds old ways of thinking in an old tongue. She is unmistakably original and completely her own woman, owing nothing to anyone else in the field: Níl ann ach gur/thug mo shúil/taitneamh éigin duit, a stróinséir –

‘It’s just that

my eyes lit

up at the sight

of you,

someone

out of the blue,

that I left behind

at the end of the night

before I came to

with an aftertaste

of Guinness

and something

little less than remorse

in the light

of the morning after.’

(Áiféilín ‘Some Slight Regret’ trans: Peter Fallon)

The voice is so contemporary, so young, so free of the chains that bound us to the task of Irish poetry forty years ago. It is a joy to think that these very young poets, O’Sullivan and Ní Ghearbhuigh, now walking the campus of University College Cork as permanent members of its teaching staff, secure in their lives, making a new Irish future, that these poets have decades, even generations, of life ahead of them. They don’t just occupy spaces vacated by lost male poets of the same campus, they create a new kind of space with new kinds of meanings and challenges for poetry. They are not just map-makers, they are creators of a new poetic landscape. And this is the reason why we should read them. Yes, it is the reason why men should read women poets – we should read them for the landscapes we once excluded from our own thought processes, we should read them for that ‘new territory’ as Eavan Boland described it so many years ago. It is not just the story of the long struggle to reach the full story of poetry, it is not just that long struggle that give’s women’s poetry its moral power. It is something more ordinary than that, something obvious to those who pay attention to texts and contexts. It is just that women’s poetry in the last forty years has created a new, larger aesthetic; a larger way of thinking about poetry, as well as life itself.

© Thomas McCarthy