The Lea-Green Down edited by Eileen Casey.

Published by Fiery Arrow Press. Sincere thanks to the Patrick Kavanagh Resource Centre at Inniskeen for all their support

Originally from the Midlands, poet, fiction writer and journalist, Eileen Casey is based in South Dublin. Her work is widely published in anthologies by Faber & Faber, Dedalus, New Island, Arlen House, among others. She has published prose and non-fiction collections (Arlen House) and poetry (New Island, AlTenTs). Awards include a Hennessy Literary Award for Emerging Fiction and a Katherine and Patrick Kavanagh Fellowship. Recent awards include the 2018 Trócaire/Poetry Ireland Award. Her work has also been broadcast on RTE’s ‘Living Word’ and ‘Sunday Miscellany’.To date, The Lea-Green Down has featured at The Irish Writers Centre, The Patrick Kavanagh Resource Centre and Tullamore Library, County Offaly. Currently, she is working on a collection of new poems ‘Aves’ (Working Title) with support from Offaly County Council. The Lea-Green Down is available on Amazon, Dubray Books (Grafton Street, Dublin and Shop Street, Galway), Books Upstairs and Kenny’s Bookshop, Galway or from publisher numberninebirr@gmail.com

The Lea-Green Down is an anthology which includes over 60 poets responding to the work of Patrick Kavanagh. Fifty years since his passing, it seems fitting to revisit the world of Kavanagh’s poetic prism from a contemporary perspective. The idea for this anthology came to me in mid-2017 so I mentioned the possibility to friend and writer Joan Power. She promptly sent me a poem in response to ‘The Weary Horse’, which writes Kavanagh’s disenchantment and disillusionment with language. Joan’s poem ‘The Garden’, showed me pretty quickly that the idea had merit. Her entreaty to Kavanagh regarding the redemptive power of language is in her opening lines ‘Oh pour me poetic redemption, Paddy,/to ease this new banality of living/stripped of wonder or beauty./Pass me the bones of your words/for there is no chink of light,/no wink and elbow language of delight/only the Babel of Google/to barrow my brain/with dreeping dung.’ Joan Power restores language to its rightful elevation, its redemptive ability to heal while also acknowledging that even the ‘bones’ of Kavanagh words are meaningful. Technology may free the world to do all sorts of wondrous things but it’s still a sobering thought that language might be suffering as a result.

The Lea-Green Down is an anthology which includes over 60 poets responding to the work of Patrick Kavanagh. Fifty years since his passing, it seems fitting to revisit the world of Kavanagh’s poetic prism from a contemporary perspective. The idea for this anthology came to me in mid-2017 so I mentioned the possibility to friend and writer Joan Power. She promptly sent me a poem in response to ‘The Weary Horse’, which writes Kavanagh’s disenchantment and disillusionment with language. Joan’s poem ‘The Garden’, showed me pretty quickly that the idea had merit. Her entreaty to Kavanagh regarding the redemptive power of language is in her opening lines ‘Oh pour me poetic redemption, Paddy,/to ease this new banality of living/stripped of wonder or beauty./Pass me the bones of your words/for there is no chink of light,/no wink and elbow language of delight/only the Babel of Google/to barrow my brain/with dreeping dung.’ Joan Power restores language to its rightful elevation, its redemptive ability to heal while also acknowledging that even the ‘bones’ of Kavanagh words are meaningful. Technology may free the world to do all sorts of wondrous things but it’s still a sobering thought that language might be suffering as a result.

*

The arrival of a weather event, The Beast from The East ensured the work got done. Though blizzards of snow raged across the landscape, I received a blizzard of new poems (via technology it must be said, email does have its merits).

The Lea-Green Down also includes the original Kavanagh poems by kind permission of the Kavanagh Trustees via The Jonathan Williams Literary Agency. The original Kavanagh poems are taken from his Collected, 2004, edited by Dr Antoinette Quinn and span the years from 1929 – 1959.

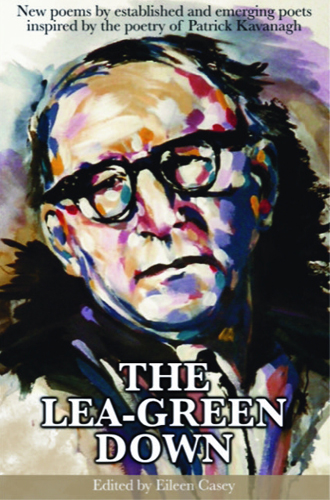

Good humour prevailed throughout the process. Visual Artist Eoin Flynn, whose poem ‘Blow-ins’ is included in the collection, designed the striking cover layout (which includes a flap cover) and of course, the cover image is by award winning Monaghan artist Paul McCloskey. Both Offaly and South Dublin County Councils contributed vital grants. The title of this publication was ready made in one of Kavanagh’s early poem ‘Ploughman’ .The idea of the plough making art reminds me of the philosophy of William Morris, 19th century founder of the Arts & Crafts Movement. Morris believed that art and function could co-exist. With regard to poetry, the poet ploughs with his pen, the lea-green of the imagination.

In a speech delivered at the Kavanagh Resource Centre, Inniskeen in 2014, Michael D. Higgins made the point that “it was a fact that if you wanted insight into the truth of Irish existence, you had to turn to literature.” Poems in The Lea-Green Down range from elegy to the politically aware, from the personal of memory poems, to present day universal realities. Mary 0’Donnell’s ‘The Blackbird, God Almighty and Allah’ mourns and remembers the dead children of Syria, murdered by Bashar al Assad. Jean 0’Brien’s ‘Child’ is an emotionally charged, non-sentimental poem dedicated to the lost children of Tuam’s Mother and Baby Home. Connie Roberts, ‘My People’ addresses institutional abuse and provides an ironic counterpoint to Kavanagh’s poem of the same title. Connie has been invited to read her poem at an upcoming conference on Trauma in Boston University. Which proves the contemporary and authentic nature of these poems, how courage as well as technical ability reveal themselves. These are poets writing out of the times in which they live, bearing witness which is very much the role of the poet. As Shelley once said: Poets are the natural legislators of the world.

I invited Gerard Smyth, well known poet and editor of the Irish Times Poetry Section, to come on-board. The addition of his essay greatly enhances the anthology. He evaluates Kavanagh’s importance as a vital mentoring agent and that while the poet was alive, young poets gathered around him in Dublin of the 1960s. Kavanagh had a clear message for them regarding ‘the necessity of renewing tradition rather than echoing it and that there was a need to push the boundaries of Irish poetry”. Una Agnew, Kavanagh Scholar and Academic, contributes a poem and commentary, again making an invaluable contribution.

So here it is. The Lea-Green Down. Fifty years after the passing of Kavanagh, over sixty poets from all avenues of poetry responding to his work with poems that bring Kavanagh where he belongs, into the centre of modern poetry. As a poet, how do I personally relate to Kavanagh? I didn’t encounter him in my early school-room years but of course, later studies brought him into my orbit. Although I’m a townie, I could still identify with poems of the soil, the sense of mystery and reverence pervading them. My poem ‘In Praise of the Dance’ is a response to Kavanagh’s ‘Come Dance with Kitty Stobling’ and while Kavanagh opens his poem with No, no, no…I reply with a resounding Yes, yes, yes. Poems like ‘Ploughman’ and ‘A Christmas Childhood’ remain personal favourites. These poems share glimpses of the divine, are luminous with spiritual energies. I could easily get beneath their skin though my father never played the melodeon and our neighbours weren’t the Lennons or the Callans. Our neighbours were the McGarrys and the O’Learys. My father was a postman, though my mother had come from a farming background and could certainly milk a cow though I’d never seen her do it. My mother sowed on a Singer Sewing Machine and it’s to those rhythms I’d fall asleep to each night. As I delved deeper into poetry, I found echoes of Kavanagh in other poets, William Blake for example, a firm favourite and one I would always want to read. In ‘A Christmas Childhood’, when Kavanagh says ‘To eat the knowledge that grew in clay/and death the germ within it, I find an echo in Blake’s ‘The Sick Rose’:

O Rose thou art sick./The invisible worm,/That flies in the night/In the howling storm/

Has found out thy bed/Of crimson joy:/And his dark secret love/Does thy life destroy.

Kavanagh’s trust in the imaginative powers resonates deeply with me. When I came to Dublin at the age of 18, I worked as a shorthand typist for Coras Iompair Eireann in Heuston Station. Kavanagh had left the cloistered world of Mucker and travelled to Dublin also though in his case, he walked the 80 miles or so. In his poem ‘Innocence’, he shows his desire to step outside the world of ‘whitethorn hedges’ yet there’s a note of ambiguity here when he says ‘But I know that love’s doorway to life/is the same doorway everywhere.’ I much connect with Kavanagh’s migration from rural to city and as such, my own early poems were also concerned with this experience, an awareness that more or less came full circle with the arrival of other cultures to our shores, an influx that became very noticeable around 2008.

Apprentice and established poets alike identify with Kavanagh’s reverence for place, how he could create his own kingdom with even the smallest detail drawn from nature. Kavanagh had a sense of confidence about his work but there was that sense of melancholic doubt about its ability to endure also. In his preface to ‘Self-Portrait’ in 1967, he wrote that “continuation was everything”.

Poets in this collection come from every county in Ireland. Northern poet Paul Maddern was drawn to Kavanagh’s ‘Pygmalion’. In recent conversation with Maddern, he told me that “Kavanagh indeed provides a bridge between Yeats and Heaney. The somewhat ‘cathedral voice’ of Yeats is tempered by the earthier tone and diction of Kavanagh. Yeats is for the grand occasion but Kavanagh is for the recognition of the beauties and the hardships of daily life”. Maddern returns to both poets regularly and regards them as ‘The Ying and Yang’ of Irish poetry. Maddern chose ‘Pygmalion’ to respond to, lured by opening lines which reflect his current occupation. Kavanagh’s lines are ‘I saw her in a field, a stone-proud woman/hugging the monster Passion’s granite child.’ Maddern has recently bought an old mill and he chose the Kavanagh poem because he’s working a lot with stone, lifting and moving them to create a garden in the process. The Heaney-like compound word, ‘stone-proud’ caught his eye and in the last line of the Kavanagh poem, the compound ‘clay-sensuous’ he finds incredibly attractive.

*

Extract from Gerard Smyth’s Essay in The Lea-Green Down

“Unlike the The Hospital and Canal Bank sonnets and other lyrics of his poetic rebirth in the 1950s, The Great Hunger is not a work that brings to mind the word celebration yet it has its moments of “profoundly simple, wondrous music” ( qualities the American Robert Creeley recognised in Kavanagh ) among the many strident notes striking a rebellious blow against what Kavanagh witnessed and depicts with lyric ferocity in the poem – the claustrophobic Ireland of the immediate post-Independence years.

In his Self Portrait he refers to it as a work that lacked “the nobility and repose of poetry” and declared that it contained, “some queer and terrible things”. That self-judgment on the poem, his statement that it lacked the nobility of poetry, is quite wrong as time has shown.

Seamus Heaney who praised its “psychic force” – and described it as a “kind of elegy in a country farmyard “ – reminds us of the question that Kavanagh asked himself at the start of The Great Hunger: “Is there some light of imagination in these dark clods”. Heaney declares, and quite emphatically, that the answer is a triumphant yes.

As for those “queer and terrible things”, the poet’s antennae were well focused and acutely sensitive to what was happening in the undergrowth of Irish society. The impoverishment of those times, material and spiritual, stands at the heart of Kavanagh’s discourse.

In his fine book-length study of the poem, Apocalypse of Clay ( Currach Press ) Desmond Swan describes it as Kavanagh’s “journey into a post-colonial heart of darkness in the country”.

The Turkish poet Oktay Rifat said that “it is the duty of the words in a language to make us visualise reality”. In The Great Hunger Kavanagh adheres to that duty with powerful results; the “psychic force” that Heaney saw in the poem is equally matched by its documentary force, and neither quality was given sufficient credit or credence on initial publication.

Here we have Ireland, ruled over by the trinity of the earth, the mother and the church. De Valera’s idealised land of “comely maidens dancing at the crossroads” – an Ireland that produced emotional cripples such as the poem’s protagonist, Patrick Maguire. An Ireland that sang dumb and by its silence, condoned, the abuse of authority, including the misuse of parental authority and the failure of true maternal instincts to overcome more selfish considerations, one of the afflictions suffered by Maguire and a major theme of the poem. Kavanagh looked well beyond his own local horizons in the poem which, as Swan points out is “a cunningly disguised diatribe against the celibacy rule of the Catholic church” and is a poem of “protest and prophecy” in which the poet reaches deep into the Irish psyche, seeing what others at the time failed or refused to see – a poet’s diagnosis of a sickness masked by the pieties of the time”. – Gerard Smyth

*

Included below are some commentary from poets as to why they chose a specific poem to respond to:

Anne Fitzgerald

‘Raglan Road’ transports me to Christmas Day in The Palace Bar , early 1970s. Family tradition dictated that my Mother’s relatives arrived at our house on Christmas morning. From Sandycove about fifty or more of us would head in to Fleet Street arriving flotilla-like at the door of The Palace Bar, where my Mother’s brother, Bill Aherne would let us into his fine emporium. Before not too long there’d be cousins Jiving on the counter top, children showing-off Irish dance steps, empty Fanta bottles and sweet wrappers abandoned, adults huddled in corners dressed in their best, and the scent of Villager cigars burning into the afternoon as turkeys overcooked – all the while Barney McKenna would strike up Kavanagh’s lament Raglan Road on his banjo. Which was to remain and to resonate long after we had sung Show me the Way to Go Home —-

Kavanagh is omnipresent, he is in our bloodstream without our even knowing –

*

Geraldine Mills

I discovered Patrick Kavanagh’s ‘Memory of my Father’ between the covers of Soundings, that anthology of poetry compiled by Augustin Martin, when I was doing my Leaving Cert. The poem had, and still has, a personal resonance for me, my father being one of the many who emigrated to London in the Hungry Fifties. He worked there from the time I was three until he died when I was nine. The sense of separation and loss that seeps from Kavanagh’s poem is one that I can readily identify with. It was something that I wanted to capture for today’s reader, in my response ‘I Keep Looking’ .

*

Contributing poets are:

Una Agnew/Chris Allan/Ivy Bannister/Tony Bardon/Patricia Best/Pat Boran/Christine Broe/David Butler/Niamh Byrne/Georgina Casserly/Jane Clarke/Declan Collinge/Harry Clifton/Susan Condon/Susan Connolly/Celia de Fréine/Orla Grand-Donoghue/Theo Dorgan/Gavan Duffy/Doreen Duffy/Derek Fanning/Pauline Fayne/Tanya Farrelly/Anne Fitzgerald/Eoin Flynn/Brigid Flynn/Marie Gahan/Enda Coyle-Greene/Mary Guckian/Jim Hyde/Breda Joy/Brian Kirk/Eithne Lannon/Ann Leahy/Aine Lyons/Phil Lynch/Eamonn Lynskey/Paul Maddern/Anne Marron/Paula Meehan/Colm McGlynn/Liz McSkeane/Geraldine Mills/Mae Newman/Trish Nugent/Jean 0’Brien/Clairr 0’Connor/Mary 0’Donnell/Maggie 0’Dwyer/Lani 0’Hanlon/Nessa 0’Mahony/Joan Power/Connie Roberts/Rosemary Rowlie/LarryScully/Tony Shields/ Gerard Smyth/ Lynda Tavakoli/Ruth Timmons/Maria Wallace/Grace Wells/Michael J. Whelan/Marídé Woods.

*

Established in 2009, Fiery Arrow is a small, independent press. To date, Fiery Arrow has published a number of community based anthologies (South of the County: New Myths and Tales, Flavours of Home) together with debut poetry collections. In 2016, Reading the Lines featured as a Live Encounter Journal. Circle & Square, an anthology of prose, fiction, poetry, drama and photography, won the CAP (Carousel Creates/Aware Prize) in its category, sponsored by Easons and Dubray Books. In December, 2018, Fiery Arrow will publish The Frayed Heart, a collection of micro-poems and haiku by Orla Grant-Donoghue, themed around love, loss & hope.