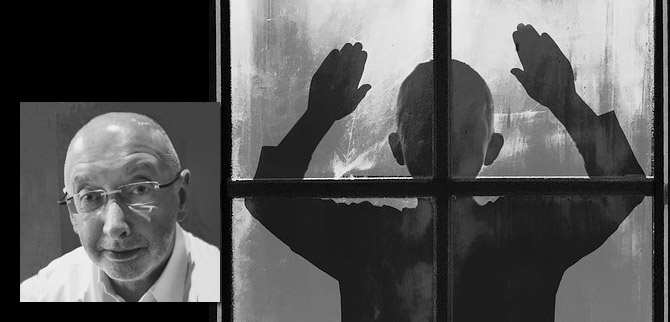

Voyeur, a short story by James Martyn Joyce

James Martyn Joyce is from Galway. He has published four books, including editing Noir by Noir West: Dark Fiction from the West of Ireland (Arlen House). His work has appeared in The Cúirt Journal, West 47, Books Ireland, Crannóg, The Sunday Tribune, The Stinging Fly, The Shop, The Honest Ulsterman, The Stony Thursday Book and Skylight 47. He was shortlisted for a Hennessy Award in 2006, the Francis McManus award in 2007 and 2008 and The William Trevor International Short Story Competition in 2007 and 2011. He has had work broadcast on RTE and BBC and has won the Listowel Writers Week Originals Short Story Competition. He won the Doolin Writers Prize in 2014. He was a winner of the Greenbean Novel Fair in 2016 with his novel, A Long Day Dead. His second collection of poetry, Furey, was published in June 2018 by Doire Press.

When the autumn came I left a woman in Rome and drove north. Rob, a Dutch friend, had settled in The Hague and was doing well as a photographer, turning sandy cement-scapes into holiday destinations through his lens. He was criss-crossing the globe, business class, laptopped and digital, capturing destinations with ‘exclusive’ pinned to them in the tour-shop windows and on the holiday websites. He’d told me I could share his flat while I sorted out one or two things, a job and a room to begin with. He was a good friend, I wouldn’t wound him.

When the autumn came I left a woman in Rome and drove north. Rob, a Dutch friend, had settled in The Hague and was doing well as a photographer, turning sandy cement-scapes into holiday destinations through his lens. He was criss-crossing the globe, business class, laptopped and digital, capturing destinations with ‘exclusive’ pinned to them in the tour-shop windows and on the holiday websites. He’d told me I could share his flat while I sorted out one or two things, a job and a room to begin with. He was a good friend, I wouldn’t wound him.

Rob had a two-roomed apartment on a quiet street just off Frederik Hendriklaan, the coolest street in The Hague. This was a not an Irish type flat: a square of cement, cheap wiring and a thin door. No, this was half a house, on two levels, Lego-style, stitched in and out of the other half, with a glass back wall to roof height, overlooking the tiny back garden. A house, but tasteful, like the person who’d designed it had actually cared.

At night I could hear the other tenant, a middle-aged woman crossing her floor above my head, vacuuming her carpets, cooking food, or her early step on the stairs in the morning. That was before I managed to pick up a job and took to leaving before her.

I collected the key from a friend of Rob’s who ran a fruit stall on ‘The Fred,’ as Frederik Hendriklaan was called. I tapped him for work at the same time, and when he heard I spoke English and all, he told me to keep in touch, he had someone leaving in a week or so and I could use the time to settle in.

It’s funny how cooking and travel go so well together. If I was still at home my mother would be doing everything, the cooking, the cleaning, and the dirty clothes. Yet here I was, three years gone, with a selection of passable dishes to my name, self-sufficient to a large degree, my clothes clean most of the time and the sky hadn’t fallen in.

So I stocked up one of Rob’s kitchen cupboards and spent a day or two walking here and there to learn the streets. In the evenings I’d toss a pasta dish together, or grill some fish, settle back, maybe watch the English news channel or read a little. I wasn’t a great TV person anyway.

It was almost a week before I even noticed the family. They occupied the apartment across the back lawn, another house on another street but backing onto mine. It was the light I noticed first. Maybe it was the autumn closing in, but I noticed how the young mother would move from room to room every evening, turning all the lights up full, blazing the Edison glow across the little patch of grass, turning the bright walls brighter. She carried a baby across her arm, a little girl of two or so following her, trailing some toy or just clinging to her mother’s dress. Sometimes the mother would sit and read to her, or feed the baby, or sit thumbing through her phone, just being there, living.

When her husband, or partner, or whatever, came home in the evenings the whole family would spring to life and he’d kiss the baby, change his clothes for a tracksuit, organise the cooking, the little girl now clinging to his trouser leg.

Sometimes I’d think of the woman in Rome, how quickly I’d left and why. A few times I slipped the Italian SIM card back into my phone and read through the texts, but after a week or so they stopped coming and after that I didn’t bother.

One evening the little girl pressed her face to the cold glass of the window pane and filled it with her breath, the fog spreading out, and then she did squiggles and drew lines across it. I could see her lips moving and imagined her little-girl song.

Sometimes I’d stop on my way between rooms and watch. The father would move quickly through the scene, passing out plates of food or tossing the baby high above his head, the little girl a satellite in his wake. Other times he’d return, the girl wrapped in a towel or dressed for bed and she’d run as fast as possible, her tiny legs almost too quick for her body and he’d pretend to chase her, the mother hurrying to hide her before they’d all collapse in a jumbled heap and he’d scoop the girl up and carry her away, book in hand.

After a while I found the family were better than television. I’d pull the big chair around, the lights dimmed, my full plate propped on my knee. I’d follow their little happenings, the baby stuffing its hand into its mouth, the mother talking, pulling the baby close to her face, the way the baby would shy from the contact, but smiling, catching its breath. At other times the little girl would paint a picture on the small easel with the cheap paper roll. The mother pulling a fresh strip into place and the little one would cover it in paint, no image, but a collision of colours erupting from the white page.

I grew to anticipate the burst of light in the evenings, the rooms flooding, the tableau settling itself, the father cooking, the mother folding baby clothes. After almost two weeks the fruit seller told me he had hours for me and I took to leaving in the dark, the stall opening early, shoppers on their way to work. The stall owner liked the fact that I was Irish; he had many English-speaking customers and was happy to let me deal with them, so I fitted in, weighing potatoes, sorting fruit, getting acquainted with the more exotic roots, enjoying the banter.

One evening towards the end of my first week there the father stopped to buy clementines, piling the golden fruits into a large paper bag. He selected them carefully, checking that the skins were slightly loose, rolling them in his grip, taking more care than many customers. I was wary of him, for no reason that I could explain beyond knowing in some small way how he lived. I felt like I’d looked into his life, an invasion almost.

‘Just the clementines.’ His accent was a surprise, further west than my own, but Irish all the same. We’d turned language into an apologetic art, the ‘just’ offering some apology for not buying more, like he owed the stall-holder and myself some level of support beyond the simple buy and sell.

I nodded. Maybe I should have spoken, but for a second I felt some irrational dislike, a small hatred bubbling up in me, so I took his coins, tossed them in the till and offered him the change.

When I got home that evening it was dark, the rooms across the lawn already blessed with light. I pulled the chair closer to the tall glass until I could feel the cold coming off it, cracked one of the cans I’d bought along the street, and sat watching.

The family were finishing dinner, the little one eating as she stood beside her mother, the baby feeding, cupping the mother’s breast. The father cleared the dishes away, easing out of sight as he carried the plates to the kitchen area at the rear.

He returned and placed the full bowl of clementines in the centre of the table and sat and peeled the golden skins from the small fruits. He offered the first one to his wife then peeled a second one for the little girl, the fruit looking big in her tiny grip.

I no longer felt hungry, the beer filling me. I cracked the second can and sat, the darkness coming down over the garden and I thought again about Maria, the woman in Rome. I even took the Italian SIM card from my wallet and slipped it into my phone, but when I powered up my phone no text came through.

The father was back now, the little girl wrapped in a big towel. She played with his thinning hair as he dried her, and then she ran quickly to her mother on the couch, the over-sized pyjamas almost tripping her.

I jumped when my phone glowed, the delivery tone taking me by surprise. I thumbed quickly but the message was a generic one welcoming me to Holland, offering me the usual terms, telling me how much they cared. I couldn’t be in the apartment after that, so I went along the street to a local bar and drank until midnight. The family was in darkness when I returned, the windows blackened and opaque.

‘We did not get your name last night?’ the barmaid asked when I stopped in for a beer again the following evening. ‘I am Monique. Now that you are back you are a regular, so we must know your name.’

‘Thomas, my name is Thomas.’ And she called my name to the other patrons, who saluted through the smoke.

‘You are visiting?’ she asked, smiling. She was giving me at least ten years, but I’d learned that all games were fair once you left Ireland and passed through Calais.

‘No, I live here, I work down the street.’ Maybe it had been a mistake to come back for another beer, but I could feel Rob’s house closing in around me. I took my drink and sat at the table near the door.

He was a surprise when he pushed through almost an hour later, the woolly hat pulled low and Monique waved, a chorus of ‘Fergals’ greeting him.

‘And this is Thomas,’ the barmaid said, giving my name a Germanic inflection. He nodded ‘Thomas’ and that was it, the conversation easing him in, the laughter coming, and the inclusive, insider jokes.

I had three beers that night; Monique brought each one to my table at my barest nod. She leant in, letting me see the offer, but I let it go. When I left, the father was not at the bar, toilets probably, and I stood outside, the Dutch cold biting me, and fixed my collar. He pushed through the door, woolly hat in place, still shuffling into his parka.

‘Good night, Thomas.’ His call was unexpected as he eased past, giving me his ‘shit’ smile, the one we keep for everyone. I mumbled a gruff reply and he was gone.

I cracked open another can when I got back to the apartment and eased into my usual chair. The lawn was almost white in the moonlight, the tall windows beyond it a curtain of black. Then the lights flickered and pulsed, the living room bursting with brightness and he entered carrying the little girl in his arms. She was crying hysterically and he stroked her hair and held her close. The mother followed, kissing the child’s cheek and talking to her. I could see the tremors running through the tiny body. Maria’s child had woken once in the night like this. Night terrors, Maria had called it, the child quivering with fear at some dream in her head, a horror untold.

Fergal sat on the broad sofa cuddling her. His wife kissed the top of the child’s head again, bent and pecked his cheek before leaving the room and he settled down to comforting her.

I sat and watched, Maria and her daughter turning in my mind’s eye. The little girl was playing with her toys now, putting plastic utensils on the play cooker near the window. The father stood and adjusted the lighting until the room was almost a dimmed stage, then he knelt, helping her to place the toys back in their storage box.

The girl moved towards the window and breathed on the cold pane, her breath a hot fog. Then she pressed her tiny fingers to the glass and cleared a circular smudge, drew a second eye close to the first. She brought her face closer to the pane until I felt she was looking straight at me across the pale lawn, her huge, round eyes fixing me like Maria’s child had done when we’d first met in Rome.

It’s well after midnight now and I’m halfway down another beer. The local bar is empty except for the pool player asleep on the stained baize, his empty glass beside him. Monique had smiled when I pushed through the bar door, like something had been decided between us. I can still see the little girl’s eyes, their cold certainty, almost like she could see me, and I can’t get Maria out of my mind.

It’s well after midnight now and I’m halfway down another beer. The local bar is empty except for the pool player asleep on the stained baize, his empty glass beside him. Monique had smiled when I pushed through the bar door, like something had been decided between us. I can still see the little girl’s eyes, their cold certainty, almost like she could see me, and I can’t get Maria out of my mind.

I could be south by mid-morning if I left now, I could drive through the night along the abandoned motorways, through the few tunnels, the hum of the engine lulling me. I can see myself easing through the doorway of the restaurant where she works, explaining how her child had been a surprise to me, appearing, as she did, after we’d been together for four months. How Maria had never mentioned that she had a child that lived with her grandparents, how wrong I had been to be angry at the time.

I can see all that as the pool player gives a drunken snort and settles again. I focus on my car keys resting on the table, and Monique places another full beer beside my half-finished one and smiles and laughs her tempting laugh. I know I need to take those car keys and leave. I need to do it now.

© James Martyn Joyce