Book Review of Suniti Namjoshi’s Aesop The Fox, Spinifex 2018 by Dr Hilary Perkins

Dr Hilary Perkins is an academic from the UK who taught for several years at Southampton University during her PhD candidature, delivering seminars on Modernism, Critical Theory and Romanticism. In addition, she contributed to Southampton University’s public engagement project TEAtime where she lectured on Shakespeare. Her PhD entitled: ‘Plastic’ Perspectives Ecocriticism, Epigenetics and Magic Real Metamorphoses in the fiction of Suniti Namjoshi, Githa Hariharan and Salman Rushdie explores the powerful potential of ecocritical readings of Magic Real Metamorphoses. She has given papers on the writing of Suniti Namjoshi and Githa Hariharan: ‘Transformation, Transgression and Transnationality. The fables and poems of Suniti Namjoshi’ at a conference of the British Association of South Asian Studies, and ‘A “hodgepodge of Greek Myth, Hindu experience and Christian words” – towards an Atopian Global Poetics in Contemporary Postcolonial Women’s Writing’ at the Postgraduate Contemporary Women’s Writing Network Conference at Goldsmith’s University.

“Who are you?” he asks me. Aesop tells him that I’m a figment from the future.

“She thinks she can rewrite my fables,” he adds scornfully.

“No, not rewrite,” I explain patiently. “Just write new ones, some of which might be based on yours.”

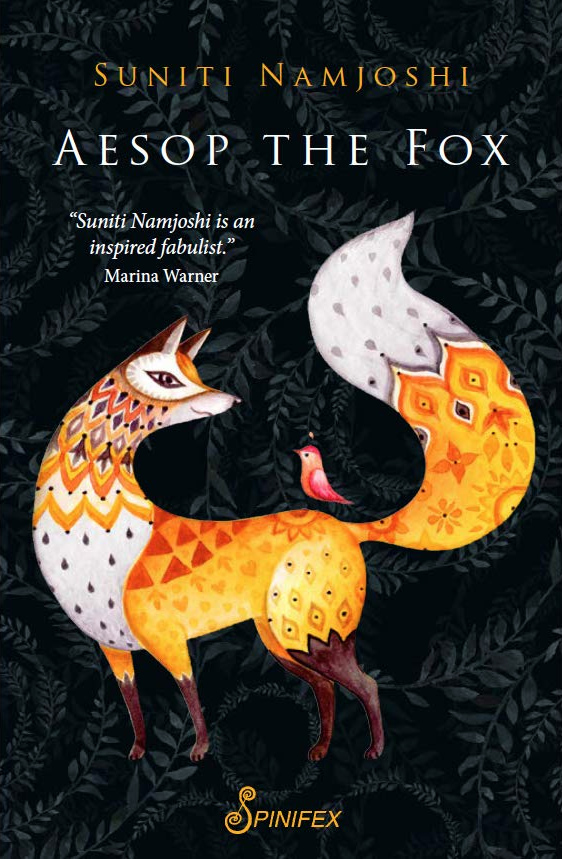

Namjoshi’s latest work, Aesop the Fox is a fascinating elaboration on her previous revisions of fable. Whilst still containing her insightful and radically satirical interpretations of traditional fable, she further develops this novel into a profound commentary on authorship and the relevance of fiction to survival in the modern world.

“I don’t re-write them really. I just use them to make new ones. Your fables are like the Bible or Shakespeare or even Homer. Everyone knows them.”

Aesop’s tales are ubiquitous, but other than he was a slave very little is known about him. Some have claimed that his slavery influenced his fables, indicating ways to survive in an essentially hostile world: ‘This is not an easy world to survive in. Which world is? Was.’ Namjoshi describes the significance of Aesop’s ‘exploding stories,’ and their revisions over time, as central to understanding human existence, not only from an individual perspective but from a global perspective across time and location: “We live in time, Sprite. Don’t you understand? The dream mutates and shifts.”

At the beginning of the narrative, Aesop physically ‘yanks’ Namjoshi – as the character Sprite – into the past. They discuss and swap stories until they are seemingly indistinguishable: “If that’s Aesop, then who am I?” Both are engaged in crafting and revising fables that are ‘repeated, mutated, fizzing with energy,’ not merely old-fashioned stories with a simple moral message, but collective tales that ‘hold up a mirror so that we’re forced to see that the way we carry on really won’t do.’ Indeed, in an interview with Kausalya Santhanam in The Hindu, February 20th 2000, Namjoshi states that fable is an essentially didactic genre, ‘able to answer questions’ concerning issues such as ‘racism, gender stereotyping and attitudes towards exploitation of the planet.’ The narrator/character of Namjoshi/Sprite in Aesop the Fox, similarly asserts this responsibility:

Isn’t it our job to do something? Say something? Tell the whole damn species to get a grip and grow up somehow?”

Although this is clearly a huge responsibility to place on authors and fiction, it has been argued that fables are well placed to convey such anxieties. Despite some scornful accusations of juvenility, fables have long engaged human sympathies and imagination. They have been universally popular, amusing, and oddly credible over hundreds of years. Thus, it may be that they have the powerful potential to address what Namjoshi identifies as the ‘mess’ we are in. Namjoshi/Sprite emphasises this potential when telling Aesop about Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, noting the way both Swift’s satirical commentary on society was initially misconstrued and underestimated; similarly derided on the basis of fantasy and childishness.

“There was a man called Swift. He lived a little more than two thousand years after you.”

“What happened to him?”

“After his death for about two hundred years they said he was mad.”

“And after that?”

“They turned his most ferocious satire into a children’s book.”

Perhaps, it is only such ‘ferocious satire’ that has this powerful potential. Indeed, Namjoshi’s use of satirical humour, related to the Hindu concept of Leela, the serious but playful nature of the divine consciousness, is also deceptively powerful. Whilst simultaneously recognizing the enormity and unreasonableness of her appeal, Namjoshi/Sprite urges Aesop to ‘save’ the world and is furious when Aesop claims he writes merely for fun.

“Then why do you write your fables?” I’m practically yelling at Aesop. I didn’t mean to sound so passionate, but I want some answers.

“For fun.”

This makes me angry. Then I see that he’s smiling. He’s teasing me. So I say soberly, “Yes, it’s true it’s fun. It’s done for pleasure. But if you had hit harder, if you had somehow managed to change things, I wouldn’t be living in a world that’s in the same sort of mess as this one.”

“Look, it’s a pleasant morning…Surely all this doesn’t make you feel that the world is a mess, does it?”

“No, that’s why it has to be saved.”

“And you want me to save it?” Aesop asks.

There! That’s it. It has been said explicitly. What I want is out of the bag now.

“Yes,” I reply defiantly. “You’re not really socking it to them. People either think that the fables are just cautionary or that the fables are not about them.”

Aesop shrugs. “My fables are as good as the people who read them. I can’t even control what happens.

This novel is more than a ‘cautionary tale’- it is an important and insightful commentary on collective accountability and the power of fiction to navigate and confront the modern world: ‘dearth, death and famine, horrible inequalities, and strutting four-year-olds ruling the nations!’ Something only too recognisable in the present political climate.

© Hilary Perkins