Young Street, poems by Ian C Smith

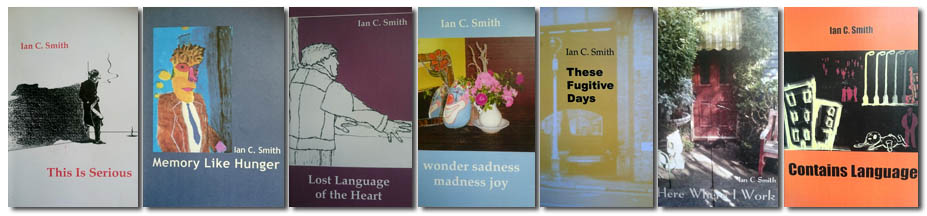

Ian C Smith’s work has been published in twenty-three countries, one more than he has visited, appearing in, Antipodes, Australian Book Review, Australian Poetry Journal, Critical Survey, Prole, The Stony Thursday Book, and Two Thirds North, among many other journals. His most recent of seven books is wonder sadness madness joy, Ginninderra (Port Adelaide). He writes, and also counts things obsessively, in the Gippsland Lakes area of Victoria, and on Flinders Island, Tasmania.

Young Street

This street replays in his mind, a street at the terminus of a city railway line in Australia where a platform ramp emptied into a bus station and taxi rank, where scenes in a movie about the world’s end would be shot, where a glamorous actor and actress guided by an acclaimed director would then vanish into movie history, phantasms on celluloid, with the cameramen, crew, extras, leaving the bright light of one day in the past captured on a reel, a street where a boy lugged holiday travellers’ bulging bags for tips, smoked cigarettes between train arrivals, plotting his escape from a home stained by unhappiness, his thoughts of the glittering city fizzing with speculation about obsessed novelists tapping at typewriters, gangsters swaggering, noirish women shimmying in black lingerie, a demi-monde of whisky-drinking musicians, gesticulating artists silhouetted in wood-panelled bars, before believing nobody could step back into this street the way it was, this relic that, so many trains, so many movies, so many whiskies later, wafts into view when he is alone, won’t be erased.

The Houdini of Disappointment

My sister lives alone, her décor camera-fed, some photographs gallery-sized. We share mostly our fraught childhood these autumn days. I tell her I ghosted away from her traditional wedding group. Though she is beyond surprises my confession triggers a search through her pictorial archive. She finds a boy, then a man, who seems to have almost always never been there.

She remembers my attempts at thirteen to flee from home, the clapperclawing chaos of our parents’ cruelty. Those damaged post-war immigrants’ DNA carried the blueprint for distress, their bid for a spangled rebirth stifled because their psycho-baggage crushed them, all of us.

Scrutinizing my sister’s wedding party, that rictus of gathered grins presaging a ghastly union, I see a blur skedaddling for the shade of conifers in the church grounds embarrassed in an older man’s occasion-bought pin-striped double-breasted suit when my preferred look was The Wild One. I smoke unobserved, longing for love, thinking of a wedding guest I have initially just seen, a girl I shall call when I finally leave home with no police alert to haul me back.

That girl, whose sweet kisses are suspended in time, would have wondered what went wrong when I stopped calling, a weakness repeated, heart a fist, a turbulent refugee slipping into grey backgrounds, early life slavering at my heels, love’s derelict, singular despite women, wives, children, ever seeking cool solace, the protection of shade, of silence, like a crying child.

His Landlady

Fleeing his severe family the boy, abetted by his older sister who had escaped earlier, entered the life of Miss Ferguson by coming to live in her narrow house where before dusk fell golden shafts of light penetrated the interior, silent but for a large clock, everything perfectly still excepting dust motes dancing.

Dancing was graceful, formal, in the youth of Miss Ferguson, now a retired clerical assistant whose voice quavered, her denture moving. She had advertised for a young woman or girl to rent a room. The boy’s sister, a trainee cook, talked a doubtful Miss Ferguson into accepting him, bumping her brother’s age up from fourteen and praising his culinary skill, keeping mum about his plat de jour, tomato sauce on toast.

Irking Miss Ferguson, he vetoed vegetables, never wanted to engage with her, brusque but not impolite, using the kitchen, bathroom, indifferent to her rules, her routine. At night he bypassed the privy in the rear porch, urinating on her grass, killing it. A child who prowled the city streets, he did manage to regularly attend work, and was far too immature for girlfriends, both saving graces.

One day instead of hurrying past he asked if she would go guarantor for a hire purchase agreement, a leather jacket a character strutting through an exaggerated American film might wear. Because he always paid his rent she agreed, and by the time he made his final repayment she had begun to grow fond of him despite how his surly expression spoiled his looks.

To Miss Ferguson’s dismay he eventually met a girl so she warned of a ‘no girls in the room’ rule, bringing a rare grin to his face as he closed his door. There were more girls, florid girls who dressed like tarts, who seemed to have a good time behind that door where they played his infernal rock’roll. She preferred the earlier days of his surly look, days without girls. In her dim passageway, still as a mouse when the music stopped, heart a trapped bird’s wings, she strained to hear a muffled throb she had never known.

A Christmas Carillon

Imagine this old man an insignificant narrator might call Grouchy, alone with idiosyncrasies, yet another Christmas nearing, memory the hot topic. Bah! Humbug! he thinks, leading to ironizing about lost names. Dickens put the kibosh on Ebenezer for boys, he muses, but darling Tim shall always be a favourite.

In the small, hot antipodean hours – Grouchy’s parents breeched his boyhood by emigrating– awake as usual, Google-doodling, he finds a photo of his first best friend, Tim, an echo of his little boy’s face from an inviolable time of frisking through horse-chestnut leaves across a frosty common after jumping off a red double-decker bus to be first to climb a coke-heap against their school fence in post-war Twickenham.

Clicking, heart quickening, Grouchy discovers tantalising tidbits. Tim, prominent in high-end business, lives on the Continent, provides contact details. Grouchy considers the word, gobsmacked, thinks Dickens would have grabbed it. Self-doubt about reaching out stabs. Foolishness? Or regret, added to a fat list? An electronic correspondence begins, a contemporary version of a writerly device from decades before their original friendship, itself decades ago.

Cautious about miracles, aware of thinking in tropes, Grouchy, who usually survives Christmas overkill comforted by characters’ triumphs and heartbreak as they head into the unknown, keeps laying aside his current solace, a trilogy of kinship by a Pulitzer prizewinner, a web connected by short chapters, one per year, as forgotten events teem back, a rejuvenation. Tim has googled him, both now stunned by what became of those impish boys, their primal choreography, conkers crammed in pockets, capering, then racing across common ground, late, the bell sounding, ever louder.

Antipodes: digitalcommons.wayne.edu/antipodes/about.html

Australian Book Review: https://www.australianbookreview.com.au

Critical Survey: journals.berghahnbooks.com/critical-survey

Prole: www.prolebooks.co.uk

The Stony Thursday Book: www.thestonythursdaybook.com

Two Thirds North: www.twothirdsnorth.com

© Ian C Smith