Randhir Khare, celebrated Indian poet and writer, author of Memory Land, Poems & Drawings,

in an exclusive interview with Mark Ulyseas

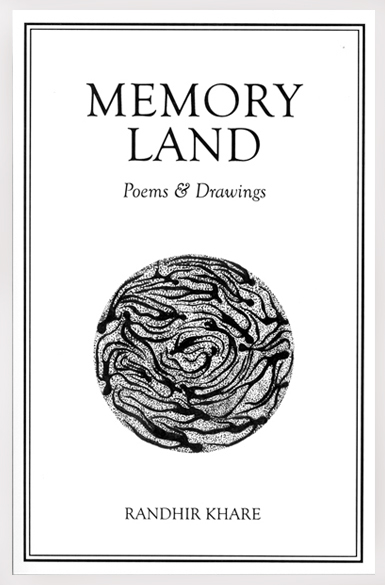

Published by Vishwakarma Publications, India, and is available at www.vishwakarmapublications.com and www.amazon.in

Randhir Khare is an award winning poet, artist, writer, playwright, folklorist and distinguished educationist who has published numerous volumes of poetry, short fiction, essays and novels and educational handbooks and has travelled widely, reading and presenting his work, nationally and internationally. He has presented his work at the Nehru Centre in London, at the Ubud Writers Festival in Bali, the India Festival In Bulgaria, at the Writers Union in the Czech Republic, in Bulgaria, Slovenia and at the Europalia Arts Festival in Belgium. In India, he has performed his poetry with various traditional and contemporary musicians and founded (and leads) MYSTIC, India’s first poetry-music band. Randhir is the recipient of The Sanskriti Award for Creative Writing, The Gold Medal for Poetry awarded by the Union of Bulgarian Writers, The Human Rights Award, The Residency Grant 2009 for his lifetime contribution to literature in English awarded by The Sahitya Akademi and The Palash Award (for his lifetime contribution to education and culture) among others.

Why have you called this latest book of poems Memory Land?

Why have you called this latest book of poems Memory Land?

The jungles of Dang in South Gujarat are alive with myths, legends, folklore and religious and community practices of traditional people.

However, mainstream steamrolling of indigenous identities has started and survival of the old ways is under threat. In fact, as I speak, some precious part of these jungles is being altered and the fabric of inclusiveness is being frayed.

This book of poems seeks to keep memory alive by celebrating the rich cultural ecology of these jungles. In times of irreversible change, memory is the only shield we have to help us hold on to what is valuable for the survival of cultural identities. Though I have not been born here I regard this my home as it epitomizes all that I believe to represent the traditional Indian ethos.

What is this traditional Indian ethos that you are talking about?

Inclusive thinking, inclusive living and inclusive being. The harmony of inner and outer experiences. A relationship web that seamlessly knits together community life and the life of nature into a sacred tapestry. Human life and divinity sharing the same space.

When one alters the rhythms of human and divine harmony by building walls of difference between faiths, customs, social and community practices and manifestations of the divine, human beings are alienated from their traditional environment and become strangers in their own homelands.

When the sacred spaces of nature are either cleared away or appropriated by the religious practices of politics, then they cease to have any relevance or meaning for those who dwell there.

Even though the jungles of the Dang have been pillaged, they nevertheless still contain the essential features and values of the Indian ethos.

Tell us about the jungles of the Dang and this relationship you share with it.

I first experienced the green world of Dang District in South Gujarat three decades ago when I visited the region to review the work of the National Literacy Mission. It triggered a passionate love affair which over the years (and numerous subsequent visits) has transformed into a meaningful relationship, taking me into the very heart of the forests and the culturally diverse communities of people settled here. Every visit has turned into an unexpected journey, revealing new realities – human, folkloric, ecological, social and spiritual.

Dang is a densely forested area which runs down the slopes of the Sahyadri mountains towards the plains of Gujarat in the west. From rugged mountains, the land dips towards low plateaus before it finally sinks to the plains, carrying river waters seawards. In the valleys and lowlands there’s rich and fertile black cotton soil whilst in the uplands there’s red soil which is dark and porous. Because of the undulating surface of the land, both red and black soil mix, creating the magic of varied foliage and ground cover. Here there are moist deciduous, dry deciduous and a sprinkling of evergreen forests which are home to a baffling range of trees, shrubs, climbers, grasses and countless species of wild life.

Across the centuries, people from traditional communities have settled here, driven by hostile armies, hunger and the need to be nourished and ‘belong’. Early records seem a bit unclear about whether it was the Mahar Koli or the Bhil who first made these forests their home.

However, they were soon followed by a host of communities including the Warli, Gamit, Kunbi, Dubla, Dhodia, Chaudhari and others. The Bhil, being the most adventurous and aggressive (as a result of the oppressive circumstances that had driven them here) successfully took on the role of resisting invasions by expansionist armies whilst the other communities settled down and established themselves. As a result of this, the Bhil are today perhaps the most economically unstable people in the region.

Despite varied cultural and social differences among the people of Dang, a pan-Dangi identity has evolved and physical spaces in the forests, vibrant with healing and empowering energies, are equally shared and revered. Ma Vali Para, for example, which is the sacred seat of the presiding Devi, is visited by people from various communities and faiths. So are innumerable other spaces.

Nature has provided the Dangis with indigenous physical spaces that attract belief beyond differences.

This is what has drawn me to the region and encouraged me to be respectful of cultural diversity and the sacredness of forests, helping me to strengthen my faith in the all-pervasive power of the earth and the need to protect and preserve our natural world.

I am not reluctant to admit that I have had meaningful spiritual experiences when among the pristine bamboo brakes of Mahal, under the mysterious star smeared dome of a Chinchali night, in desolate Gotiamal, green rich Vaghai, Wasurna and Linga (seats of forgotten Bhil Rajas), Ahwa (which has been constantly on the crosshairs of Dangi history), Dhavalidod (where I have spent nights learning the language of darkness from the late Janu Kaka, a Kunbi Bhagat) and Chikar.

From the rivers of the region I learnt patience, forgiveness and the will to go on – in life-altering ways.

What is the message that you want to convey in Memory Land?

Respect and preserve diversity. Lay your life on the line if you have to, in order to do this. Nature is an animated university…a homogeneous energy that nurtures cultures and civilizations. In your deepest, darkest hour, nature heals and supports you.

And is this the first time you have published poems with illustrations by you?

Being an artist and a poet, I prefer to give equal importance to the visual as well as written aspects of my books of poems. So, I call the visual elements of my books of poems ‘drawings’ and not ‘illustrations’. I regard my drawings as entities in themselves. The movement of lines explore the themes that the words do, in their own unique way. Together – the poems and drawings create and present varied dimensions of the same theme. This is my fifth book of poems which also includes drawings. This book differs from the others in one way – every page of words (even if it is part of a longer poem) faces a line drawing. There are more than 50 poems and more than 80 drawings in the book.

In 2000 you published a ground breaking book on the Dangs titled – The Dangs – Journeys into the Heartland. Is Memory Land a continuation of the exploration and narration of this journey?

Not exactly. Whilst the earlier book, which was a prose work, was written as a travelogue in a certain sense, this book is an intimate sharing of the experience of the human and natural aspects of the jungles. Whilst the earlier book was written by an ‘outsider’, this has been written by an ‘insider’. The earlier book was written from an outer eye view, this has been written from the inner eye view of deep reflection and affinity. My experience of the jungles of Dang has evolved – inwards.

Have you been a fine artist before writing poetry or did this come later?

Even though I started drawing much earlier than I started writing poetry, it was all in a closeted way. I never showed my work. Art was an intimately personal creative experience. The images were metaphors for my own experiences, thoughts, feelings. I began sharing my art with the outside world only about twenty five years ago. I have been writing poetry for more than fifty years now.

When I was little, my family lived in a community block with a series of outhouses which would be used as storehouses or kitchens by residents. I would sneak into the neighbour’s storeroom and steal pieces of charcoal and go around to the back of the block and draw great whirls of lines from one end of the wall to the other. I called them ‘wind lines’. Then I drew ‘storm lines’ and ‘cloud lines’ and ‘rain lines’ and ‘tree lines.

The lady of the house next door caught me, locked me up in her foul smelling bathroom and let me out after an hour with the gift of a small drawing book and some colour pencils. ‘Here,’ she said, ‘since you anyway don’t go to school, you might as well do some drawing at home, that is, if your parents don’t put you to work.’

I grabbed the drawing book and ran to our apartment. ‘Where did you steal that stuff from?’ My father asked. I was scared to tell him the whole story so I said nothing. He took away the book and pencils. I never saw them again.

But I didn’t give up and went down and stole some more charcoal then went around to the back of the block, climbed through the bars of the boundary into the slimy and disused service lane. The boundary wall was low and patched with moss and mud and other unmentionables. That was just what I wanted.

I circled the patches of moss and mud and turned them into islands. I created ‘sea lines’ to surround them. Drew ‘boat lines’ and ‘ship lines’. It took me days to cover one section of the wall, then I’d walk up and down imagining that I had actually ‘created’ all of that like some divine creature. I felt that I could command the ship, the boats, the waves to move in whichever direction I chose. Other times I created stories around my lines.

In those dismal times, the lines on the wall were my ladder to the stars.

Much later when I took my lines out to people, they first didn’t know what to do with the rawness of the work but have over the years found more affinities with them. Concurrently, my lines and textures have become more expressive.

You mention the word ‘rawness’ here. Do you mean ‘primitiveness’?

Yes, sometimes almost prehistoric. Early. Tribal. Folk. Of course, I am not influenced by any traditional form or style. But there are crossovers because in all cases Nature is the inspiration. Largely, I use lines, dots, whirls, spirals and other primal forms and shapes.

But you appear most at ease with lines. Why is that?

When a line begins to move across blank space, it charts a pristine path – creating on its way a passage of certainty…like a stream of light spearing through thick foliage flows and curves and bounces and reveals, like a river draws its own story across the body of the earth, like time inexorably marking our lives, linking experiences, cutting through the living and the dying, like the light of a solitary star gently pouring on to the back of a passing mist that sails dawn-wards. A line gains life when you allow it to catch its own flow, which is in fact the artist’s flow. I trust lines when I give myself to them.

Has any of your work been translated into any other language?

Yes. My poetry has been translated into Persian, Hindi, Bengali, Urdu, French, Bulgarian and Czech then presented to various groups of people around the world. The work has been recited, performed to music and has inspired painters, artists and photographers.

Has any of your work been adapted for the stage (theatre)?

Yes. My first play in 1971 was written in verse and performed in verse. The Ishara Puppet Theatre Company has also adapted my poems for stage performances.

Apart from my poetry, twelve of my prose plays have been staged. In fact, over the last two years I have written, produced and directed 5 new plays: Breaking Free, Flowers, Waiting and The Clown Who Knew Too Much for adults and The Dream That Changed The World for children. The premier of the last mentioned play is being premiered on June 30, 2018.

What are you working on now?

My memoir The Flood And After, a fable – Trees Live Forever for children and my new novel Talking In Tongues.

Could you give us a brief overview of your life as a poet, writer and artist?

I started drawing secretly at seven and went on to having seven solo shows of my drawings and paintings as well as two installations – one on the theme Life In A Cage and the other (in collaboration with the painter Manish Vedpathak) I Am Not Me, I Am We. My theatre work includes the adaptation of five plays for stage and voices, twelve original plays written, produced and directed by me.

As regards my published work – 37 books of poetry, short fiction, novels, translation from tribal dialects, travelogues, creative education and essays.

For the last decade I have been professionally mentoring writers of all ages (12 years to 83 years) in face to face settings and offer online master classes.

© Randhir Khare/Mark Ulyseas