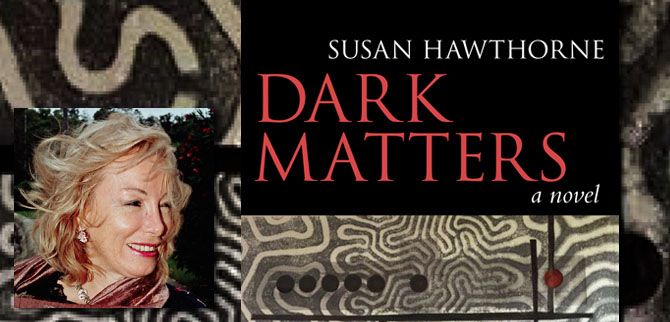

Review of Susan Hawthorne’s : Dark Matters, Spinifex Press, 2017 – by Sue Woolfe

Sue Woolfe is mainly responsible for the bestselling novel about mathematics and motherhood, Leaning Towards Infinity: How My Mother’s Apron Unrolls Into My Life, described the Baltimore Sun as ‘the deepest novel of ideas in years’, and by Fay Weldon as ‘glorious’. It won or was shortlisted for many prizes, including international ones. Her novel Painted Woman was published in Australia in 1989, in translation as Ici et à jamais in France in 2008 and it’s been professionally produced twice as a play, and on ABC radio. The Secret Cure, about a mother’s determined search for a cure for autism, is currently being adapted by Woolfe for an opera. Her 2012 novel, The Oldest Song in the World, is set in the Northern Territory in an Indigenous community, after Woolfe lived there for over a year. In 2017 she published to acclaim a short story collection, Do You Love Me or What? She teaches what’s known in neuroscience about the moment of creativity, (The Mystery of the Cleaning Lady: A Writer Looks at Creativity and Neuroscience) and takes people to beautiful places on writing retreats. http://suewoolfe.com.au/

Let me first admit it: I tried to put this novel down many times after my acquaintance, Susan Hawthorne, sent it to me. The story begins beguilingly; the narrator, during a household cleanup, is going through scraps of paper in boxes left to her by her Kate, her lesbian aunt originally from Crete, and she can’t stop reading. An ordinary situation, but as a writer always hungry for prose that’s potent, I was captivated by Hawthorne’s, and began devouring it. After a few pages I even texted a writer friend that it had the clear, crystal ringing quality of Satie’s Gymnopedies. And then came the crash:

Let me first admit it: I tried to put this novel down many times after my acquaintance, Susan Hawthorne, sent it to me. The story begins beguilingly; the narrator, during a household cleanup, is going through scraps of paper in boxes left to her by her Kate, her lesbian aunt originally from Crete, and she can’t stop reading. An ordinary situation, but as a writer always hungry for prose that’s potent, I was captivated by Hawthorne’s, and began devouring it. After a few pages I even texted a writer friend that it had the clear, crystal ringing quality of Satie’s Gymnopedies. And then came the crash:

“Day 1

I don’t know where I am. They came hooded. Shouting, waving their guns. They were wearing boots and hooded jackets. “

I closed the book. Now I have to admit that, for reasons not relevant here, I’m a hider from accounts of torture; a switcher off of violence on the news, a ducker behind the seats in front of me at movies. Even glancing at the football, I wince when a player falls over. But hide from it as I might, that image of hooded thugs kept haunting me, while I rode on a bus to work, while talking to students, while making dinner. It haunted me not because I had to know what happened next – I’m usually a sucker for a strong narrative. It was that prose as luminous as Hawthorne’s piles up inside you, sears through your defenses, my defenses, and burns them away. So at last, I had no choice. I took it up again, gingerly, but intrigued. I knew that the book moved between Chile during the 1970s and a fictional dystopia in Australia. I devoted a week, not only to Hawthorne’s book, but afterwards I allowed myself to discover what I’d hidden from 40-odd years ago, the horrific Pinochet regime in Chile, a reign of terror, during which thousands were killed or reported missing, tens of thousands were imprisoned and tortured, and 200,000 Chileans went into exile.

In Hawthorne’s novel, Kate is a farm girl originally from Crete and Mercedes a child exile from Chile who are entirely innocent of crimes, but their bedroom in Australia is suddenly invaded in the dark of the night. Mercedes is shot and Kate taken away.

The spine of the story is a serialised account of Kate’s 72 days of repeated gang rapes and torture while she’s imprisoned in an animal stall and kept hooded, but Kate spares us the worst of the details, at one point even writing:

“What happened next, I cannot recount. No. I don’t want to speak it. I don’t want to put it into words … I cannot speak.”

What she stresses is the torture of her kind.

“I cry. I cry for all. For all the women. For all the lesbians. I cry because no one cries for us. In Kampala and Chicago. We are shot and raped. We are thrown from the top floor of a high building in Tehran and Mecca. When they arrest us they put us in cells with violent men who think nothing of having their own ‘fun’. In Melbourne and on the Gold Coast, we are tossed from cars, rolled into a ditch. In Santiago we are imprisoned and put on the parrilla. In Buenos Aires they insist we accompany them to dinner outside the prison. We are caught, used and banged away again at midnight. On the Western Cape they come for so many of us that even the media notices. But most of us remain hidden. There are few reports of the crimes against us. Fewer readers. “

What’s most devastating is not even the “velvet voiced” commander who stalks in circles around her, speaking seductively then grinding her fingers into the ground with his boots, but the chilling evidence, once again, that we humans must be the lowest animals on earth – of course nature is scarlet in tooth and claw, even vermillion, but we as a particular species bring to our cruelty the brilliant brains we admire so much in ourselves, the reasoning that can explore the stars, the spiritual reflectiveness that can name and worship gods, the knowledge we’ve had passed down to us over thousands of decades. When we hurt others, we do it with the sophisticated brain machinery that can give rise to the science that figured out, amongst other realisations, the dark matter of the universe, and created the art, the literature and music of our world. We regard ourselves as the pinnacle of evolution. We harm each other with the genius of gods.

Hawthorne artfully resists making huge statements, but allows Mercedes to say at the end of the book:

“Torturers don’t need reasons. They just want ways to terrify you. … They picked us out as a group that could get ‘dangerous’. Their idea of it. None of us had any weapons but our minds and our voices. … Every generation they pick on new groups. Call them terrorist, asocials, dangerous. The people at the top hardly change. The people at the bottom are traumatised and re-traumatised.”

It is, despite this dark matter – which Hawthorne considered over 15 years of reading countless testimonies and related works – a strangely positive book. There are three narrators: Kate who’s an ex-farm-girl and ex-circus performer; Mercedes, her lover who appears at the start and the end of the book; and Kate’s niece, the young Desi. Kate’s determination to survive is inspiring, partly because she sees her suffering in the context of history and that gives her courage, and partly because of her wild hope that Mercedes didn’t die despite that shot, the hope that one day she’ll be released and they’ll be re-united. It’s also positive because of the structure Hawthorne uses of interleaving past and present, with resonances of the cows of Crete who walked across the fields in zig zags, long parallel lines going back and forth. The narrator, Desi, the discoverer and compiler of the papers, is as inspired by a joyful curiosity as her aunts once were during their courtship in Melbourne. So Hawthorne interleaves the dark matters with the young Desi’s own journey of discovery as she travels to Latin America, uncomprehending how such cruelty could happen, pinning down what actually happened, and writing it up for an academic study that may interest future scholars.

Hawthorne, a major poet and brilliant essayist, created the independent Spinifex Press and published many books of other writers, as well as fourteen acclaimed books of her own. Reading this new work by a writer who has devoted her considerable mind and her life to the creation of literature and its championing, turned out to be, despite its dark matter, an exploration of not only the evil but the courage of the human heart.

© Sue Woolfe