International Lesbians – Portraits, by Kathleen Mary Fallon

Kathleen Mary Fallon most recent work is a three-part project exploring her experiences as the white foster mother of a Torres Strait Islander foster son with disabilities. The project consisted of a feature film, Call Me Mum, which was short-listed for the NSW Premier’s Prize, an AWGIE and was nominated for four AFI Awards winning Best Female Support Actress Award. The three-part project also includes a novel Paydirt (UWAPress, 2007) and a play, Buyback, which she directed at the Carlton Courthouse in 2006. Her novel, Working Hot, (Sybylla 1989, Vintage/Random House, 2000) won a Victoria Premier’s Prize and her opera, Matricide – the Musical, which she wrote with the composer Elena Kats-Chernin, was produced by Chamber Made Opera in 1998. She wrote the text for the concert piece, Laquiem, for the composer Andrée Greenwell. Laquiem was performed at The Studio at the Sydney Opera House. She holds a PhD (UniSA).

Portrait 1

The dislocated black shadow of a black bird crosses the curtain as my eyes open.

The dislocated black shadow of a black bird crosses the curtain as my eyes open.

She has cockerel’s claw feet. She has pendulous flesh. Bulbs from her chin, from her beak. And an evil eye under her red cock’s comb. She is no red flower but a red brute. A fat chair with boob back. Riveted-nipple upholstery. And a gun in her stomach. A razor in her vulva. Claws walls with fat little ringed fingers. And the hollow tubes in her head – all the springed wires, toothed wheel machinery – is the motion of her abdomen. She is gutless Billy Bunter’s sister Betty.

Where is the child hiding? Where is the little girl I could take over my shoulder for a joy ride on my back? She is too small in her eyes to live. She is hardly a dust peck of blue in her eyes. I could touch with one finger Thumbelina in a matchbox. Never murmuring on her woebegone bed so retarded is she, such excellence at autism, at imitating vegetables.

She is a bump in my heart. She is a prisoner in this wrong country, this Anglican country of old people, this old grey mare who aint what she used to be. Italy – Genoa – was her country but she fled back, presumptuous in her freedom, back to this wrong country, to her exile and childhood, her dark amnesia. With her hands full of shell miracles, suns in her stomach, she believed she could stretch her freedom – a long elastic of sunlight – from Genoa to London but it broke the moment she saw her mother’s face. ‘You don’t shit on your own doorstep.’

What a weight to carry on the back. I could not bear it. Could not bear her massive self-hatred. The blood on her hands, self-slaughter, her child abuse.

The distance from London to Genoa is one big step but millions of little ones. With hours of surgery, years of skill, I could not find, teach or train the child to talk, eat, grow, love. The carcass is fearful to me. The baby mammal is almost dead in the pouch in this bone cold country, this milkless motherland.

The mother and child are not doing well and the mother has resigned herself to perennial pregnancy. The plant will never give up the bud to flower. It is a brown husk of deadseed in this spiceless country. The clam will never give up the pearl, embalmed as it is in a tumour of blubber.

So you came back to this dead bellied country, this deliberateness. The resolution of the railroad track. The propulsion forward in a straight line on a slow ferry. And the two white waves spreadeagled behind, spread out and straddle the Channel. And your legs never part in passion now. Raped by a slow boat to London. The ocean of amnesic smog and your mother’s bait face on the platform waiting. A hooked fish you land flat on your back, dead and bleeding from the gills. Your sea colours fading. Genoa the dream and the fear of the dream. Fishing for rainbow mackerel, in sewers, with safety pins. Howling around in the labyrinth of the Underground. You curl at night in your dark sheets, gnawing around the fear of a dream, suckle yourself in your exile.

And all the lovely women of Genoa with honey faces and beer-coloured hair laying you down in wet dreams like pine needles in nun’s beds on three times thirty nights and the singing of the sea in your conch shell ears and the grit of sand sifting inside the glass of the timer. The egg never hatches; hatches too soon and the yolk breaks.

There is no out for you here amongst the judges, the prefects, the liberal bureaucrats. Your carcass is fearful to me, a mound of dreadwood around a stilled childflame. Your hands are pulpits I climb into and cry my weakness, your misery, before morning. Your hands are Fascisti rods, Fascisti axes, giving me as they do my freedom around the fact of their penetration. Their hold on my insides.

You hold my insides snug ugly in your grubby grip.

Filled my mouth full of breastflesh, nipplepucker. Filled myself full of your selfdisgust and justdisgust. Rolled in black sheets of crude satin. Lunged drunkenly at lust and fell on top jaded, exhausted. And woke nauseous as my first kiss. And yet, growing out of this humus, this compost called sexuality.

Portrait 2

So, who’s the old girl knockin’ around with these days?

So, who’s the old girl knockin’ around with these days?

‘How far you been into it then – lesbianism that it?’ asked the old girl.

‘I been in one side and all the way out the flamin’ other so don’t give me no lesolip – it’s not worth the trouble – not worth the paper it’s written on,’ replied the other old girl.

‘I’m glad I’m not staying,’ she said on the first night. ‘I could easily fall in love with a woman like you.’

‘I love you,’ and ‘I love you so much,’ she said the second night. Flying back to Berlin the third. I guess she could have spoken German to me if I’d asked her, surely playing my cards right. And I did, oh I did. ‘Gotcha!’ I said like a crocodile in an ad. ‘How would you like this every night of your life?’ I said. ‘Bingo,’ said Tuxedo Jean. It’s taken me a week to sit and think I’ve missed something, something sexual.

‘It’s not that I love you,’ I said. ‘It’s just that so few people bring me back to a sense of myself as I am – talkative (verbal-bloody-diarrhea), humorous, seductive, arrogant, piss-weak, butch-as-all-hell, fem-as-all-shit.’

‘No one has ever touched me like that,’ she said, ‘so soft and yet so strong at the same time. I know it’s corny but it’s what we all want, sophisticated fingers. Your hands bring me down from that crazy flapping kite women can be at this time of night.’

‘Can I touch you?’ she’d say. ‘I want to touch you.’ Meaning down there. Oh! And uh huh! And yes mam! And how fabulous! (As I heard the poofta in the bus say, ‘I spent the whole three days on all fours. It was fabulous.’) Hot shit honey. Tuxedo Jean.

‘No, she doesn’t care,’ I told my girlfriend. ‘She doesn’t care much that she’s hurt you. She’s flying out of it all and it’s so attractive that attitude. That’s the attitude you must practice every day.’

‘Women – no brains,’ said the guy in the bus, ‘and happy without ‘em.’

How come some hands bring you off? How come some mouths make you?

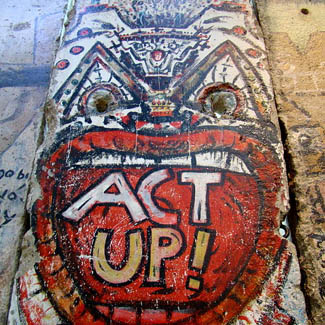

Future plans (on a small scale) – study maps of Berlin. Run my finger along the Wall. Wonder at our ability to find pleasure in the darkest places.

‘But what do you want down there?’ I asked, drunk. ‘What the fucking hell are you after?’ And she said, ‘I didn’t want to fuck you, I wanted your girlfriend at first.’ I love honesty. No, I really do. I love lack of tact. It’s a challenge to my over-socialised sense of finesse. Loving smart women with an edge to them. Take your positions; the bout’s to begin.

‘Don’t try to work it out,’ she said. ‘There’s no point and that’s what’s great.’ ‘Hang on,’ I said. ‘You get your kicks your way and I’ll get mine mine.’ Curling back into love, romance, devotion.

How attractive people are who take their pleasure where they will. ‘You only live once,’ they sing in chorus. Well, I for one want to grow out of everything I’ve ever learned.

I’m drunk and I’m beginning to miss you, Miss You, Miss Tuxedo Jean. And I wouldn’t have dreamt of laying a hand on you if you hadn’t been leaving, that absent one’s such a yum yum. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, without the shadow of a doubt, Greed and Deprivation are twins.

‘Don’t let me near a pen,’ I heard the girl in the bus say. ‘I’ll just write his name all over the borders.’

©Kathleen Mary Fallon