Flying Colours, a short story by Hilary McCollum

Fear is my enemy, clutching at me, quickening my breath. My palms sweat, my heart thumps. My mind whirrs like a trapped bird, darting from the crowd to my last imprisonment to the scarf in my hand. I see smashed windows, burning pillar-boxes, the torture trolley.

Fight the good fight with all thy might;

Christ is thy Strength and Christ thy Right.

Ever since I was a child I have found comfort in songs. Locked up in prison, in solitary confinement, I would sing aloud against the horrors I was facing. To-day in the Derby crowd, my voice is silent; my mind does the work. The hymn calms me, warding off my fear and reminding me of my purpose. I am here to do God’s work. The government is murdering Mrs. Pankhurst. Inch by inch they are squeezing the life from the leader of our movement. I cannot stand idly by and let them kill her. Rebellion against tyrants is obedience to God.

I have watched the opening races. The horses are huge, a world away from the ponies of my childhood. I did not realise how big they would be. The Derby runners trot towards me, taking their time from paddock to start line. A hurtling frenzy will replace this gentle pace in the serious matter of the race. Round Tattenham corner they will come, momentum gathering, hooves pounding, rushing for the finishing line. I will have only seconds to act.

The child in me would have me flee. Go, she says. Go.

I could go, as my frightened self would have me do. It is not too late to change my mind. Only my comrade Mary Leigh knows that I am here and even she does not know the reason. I could squirm through the crowd, walk back to the station and take the next train to London. I have a helper’s pass for the Suffragette Summer Fair. No one would know my courage had failed, no one but me. On Saturday, when Mrs. Pankhurst’s licence runs out and they take her back to Holloway prison to die, I would know I had done nothing to prevent it. I was in court in April when she was sentenced to three years penal servitude for conspiracy to commit an explosion. I could easily have been in the dock myself. In truth, Mrs. Pankhurst had nothing to do with blowing up the Chancellor’s summerhouse at Walton for which she is now facing a death sentence. All she has done is to urge women to attack property until the government gives us our rights. She has already endured two hunger strikes in the last two months. Her health is destroyed. She will not survive another. I pray my protest will save her.

We are in desperate times and desperate times require desperate measures. The government has been torturing us for years. Forcible feeding is a horror that I can barely bring myself to think of. Worse still is the abominable new Cat and Mouse Act that Mrs. Pankhurst is suffering under, a drawn out torture of hunger strike, scant recovery, hunger strike, which can only end in death.

Last year I threw myself down the iron staircase at Holloway prison. One great sacrifice, I thought, one great sacrifice to save many others. I wanted to put an end to the forcible feeding of my comrades. I have endured the violence of the feeding tube forty-nine times, each time wondering would it kill me. But hearing comrade after comrade being tortured while waiting for hell to arrive in my own cell was unbearable to me. The memory of that day still stalks my dreams. I must not think of it now.

Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid.

The words are a balm. God is with me. I put away my fear and focus on what I have to do. I have staked a position on the rail at Tattenham Corner. This is the best spot on the whole racecourse. The news camera directly opposite has a clear sight of me. There’s another one a hundred yards to my left. Between them they will surely capture my actions.

The moment is almost upon me. The crowd is thickening, clotting round my vantage point. I hold my ground. The horses pass me on their way to the start. My eyes follow Anmer, the King’s horse. On his back is Herbert Jones, the Royal jockey. Anmer is the reason I am here to-day. I note in my mind his height, watch how he moves. I wish he were a grey, a silvery white grey distinct from the other runners. But he is a brown horse in a field of brown horses. The hardest part will be picking him out. The King’s colours will help. They are like no other racing silks. The scarlet sleeves and purple body flashed with gold stand out against the pinks and creams, the spots and stripes. But the colours that matter most are the ones Anmer will carry home.

My plan was to use one of the flags that I collected from headquarters this morning but I fear the bulk will be unmanageable in the few moments I will have. Instead I will use my scarf. It was a gift from my friend Rose on my release from Holloway last year, white knitted silk, Votes for Women woven in purple and green at either end, purple and green stripes down the centre. This scarf is precious to me but it is light and easily handled. I know that Rose will understand.

Across at the start, the horses are gathering. I tune out the crowd, entering a world where only myself, my scarf and the horses exist.

And they’re off, a glimpse through the trees, a dozen horses sprinting up the hill, hooves eating up the ground. I face the bend, craning my neck for my first sight of them. I’m in luck. Anmer is out in front, clear of the other riders, his distinctive colours shining like a beacon. Quickly I duck under the rail. He’s almost upon me. I approach him side on, reaching up, reaching, reaching, grabbing the reins, slowing him down for a moment, only a moment, long enough to loop my scarf around the leather straps. The astonished jockey stares at me, his mouth open, but as the other horses catch him up, he flicks his whip at Anmer’s flank and they’re back into their stride my scarf streaming out beside them.

I dive back to the safety of the rails, narrowly escaping the trampling hooves of another runner, pushing my way back in place. I unpin one of my flags, brandishing it above my head, shouting “Free Mrs. Pankhurst. Free Mrs. Pankhurst. Votes for women. Free Mrs. Pankhurst.”

This is how I imagine it, Anmer galloping home under the colours of the cause, carrying my petition to the King. Votes for women. Please grant us votes for women and save Mrs. Pankhurst’s life. This is how I hope it will be.

I do not know what happens next. What happens next will be down to others, not to me. I may well be arrested. I am not sure what offence the police would charge me with but there’s bound to be something, there is always something. Or I might be attacked by members of the crowd, beaten and kicked, spit drenching my face, hair torn from my scalp. It has happened before. Or perhaps I will complete my protest, walk freely to the train station, return to Victoria and thence to the Suffragette Summer Fair.

The noise of the spectators brings me back to the present. A buzz of excitement vibrates through the crowd as the race gets underway. The horses’ strides are long and laboured as they climb the hill from the start. It does not feel real. It is more like a dream than reality except I can feel my heart pounding, bursting against my ribs. Time is fast and slow. The horses are taking too long, making me nervous. I want them to hurry. I check my scarf again, try to calm my breathing.

Suddenly, they round the bend, a blur of pale silks, brown horses. Where is the King’s horse? Where is Anmer? I scan the horses frantically as they pound towards me, faster than seems possible. Where?

There he is. On his own, a little way back from the leading bunch. I duck under the rail, avoiding the last of the pack. Anmer’s coming fast, ground vibrating, crowd roaring. I approach him side on, reaching up, reaching, reaching–

Hilary McCollum is an award-winning Irish writer and campaigner. Her first novel, Golddigger, which spans the California goldrush and Irish Famine, won the Golden Crown Literary Society award for historical fiction in 2016. Her second novel, Wild, set within the British suffragette movement, will be published in 2018. Her play, Life and Love: Lesbian Style, was nominated for best original writing at the 2014 International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival. She has written two verbatim plays about LGBT lives in northwest Ireland and a lesbian pirate play, The Pirates of Portrush, about religious fundamentalism. She has contributed to debates about the historic suppression and censorship of same-sex relationships between women and the role of history in shaping identity. She is currently undertaking a creative writing PhD at Queen’s University Belfast.

For more information, go to www.hilarymccollum.com. Follow Hilary on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/hsmccollum or on twitter @hilarymcc7.

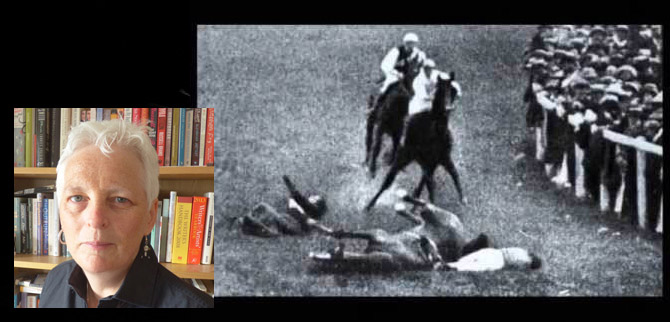

Above b/w photograph : Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was a suffragette who fought for the right of women to vote in the United Kingdom in the early twentieth century. She died after being hit by King George V’s horse Anmer at the 1913 Epsom Derby when she walked onto the track during the race to what is now revealed to be an attempt to tie a flag of protest to the King’s horse. Above photograph is a screenshot of the actual event. She can be seen on the ground on the left.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-G4fJ9I_wQg&t=13s

© Hilary McCollum