Live Encounters Books-Reviews Volume Seven

November- December 2025

Jena Woodhouse review of

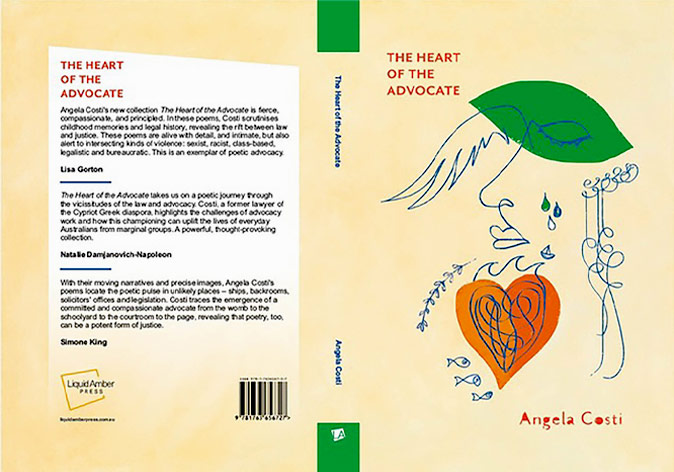

The Heart of the Advocate by Angela Costi

Liquid Amber Press (Australia), 2025

In the words of the author, poet Angela Costi, “This book brings together two previously divergent aspects of my experience— legal and poetic advocacy.” (“Opening Address,” 2)

The tension between the Law in theory and in practice; application of and adherence to the letter of the Law versus the dictates of the heart, where justice and compassion outweigh abstract legal codes, sets this collection on an incisive edge, which cuts to the heart of its matter, engendering, according to the nature of the case, recognition, outrage and empathy in the reader. One after another, the poems implode in the reader’s heart and mind, insisting not on sentiment, but action, acknowledgement, redress of the grievous wrongs suffered by the disenfranchised and the unempowered. If only by proxy, a sense of empowerment is restored to those for whom the formalities of justice are unattainable. While readers may be aware of similar instances, they are disarmed by the quandary of the advocate and the anguish of the wronged encountered in these poems, often simultaneously. The heart’s defences— if such there were— against feeling the pain of others, crumble in the eloquence and passion of these scripts, where we cannot look away, unsee, unhear what they convey.

Initially the poems follow a chronological arrangement, documenting the poet’s parents’ separate arrivals in Australia from Cyprus, and her childhood as a member of a diasporic household in an outer suburb of Melbourne. As Costi’s awareness is sharpened by her experiences in adolescence and her studies and postgraduate experience in the legal profession, the scope of her comprehension and concern broadens as she encounters or reflects on those beyond legal reach and redress for the harm that has befallen them.

In the first of four sections, “From the Womb”, we learn more of Costi’s family background and cultural values. As she explains in her “Opening Address”: “Significantly, what poetry gave me was an opportunity to give voice to the needs, desires and stories of my kin who weren’t sent to school and didn’t write. Both sets of grandparents were from Cyprus, and their backstory is one of poverty and anxiety associated with civil unrest and imminent war.” (1)

In the poems that follow, a conscious sense of identity begins to emerge, in tandem with a sense of social and personal justice, often concomitant with, or defined against, encounters with the inequities experienced by members of immigrant communities in Australia of the post-World War II period. Her mother’s passport: “British Passport 94175”(7), reveals the profile that enabled her migration.

… Your profession is ‘Schoolgirl’

without experience of classroom or study

at thirteen you continue the official lie

for Australian factories who need to

work the bones of those who don’t easily

fracture.

The second section of the collection, “Adversarial Practice”, opens with a powerful poem dedicated to “Vincent Shin, who pioneered the first School Lawyer Project… at a school in Melbourne’s outer west.” In “Case Dismissed” (24-25), the schoolgirl’s unflinching gaze sees beyond the conventional scenario her revered Greek teacher is about to enact with her imminent marriage:

By way of persuasion

I wrote an essay on Marriage….

to show tired Mama with stitched fingers from the sewing

machine. Most of the class denied their souls the truth of

their mothers’ folded arms, bent heads, bruised hearts

Only Leonie Smith raised her arm when I stood up

against rings squeezing fingers for life— we knew the fate of mothers

given no back door to exit when the front door is barred

But her urgent attempts to warn her teacher of entrapment were to no avail: the “Goddess” morphed into “Wife”.

While this second section of the collection details many instances of mortification on the path to maturity, and instances of individuals trapped in their circumstances, the dominant impression is of those who overcame disadvantage to be able to live life on their own terms and support others to do likewise. The subjects are both real and realistic, the style documentary. Not every person ensnared by a bully, or a brutal marriage, or by being cast as a social underdog, has the will or the means to escape their life situation. The poet as a high school student, young adult, undergraduate, new graduate, revisits her dreams, her influences, her ideals and aspirations, her gauche missteps, as she moves towards, and enters, her own social and professional identity, while striving for academic success and achieving it. The letter of the Law continues to hover, opaque and intimidating, as she pursues her tertiary studies, never able to dismiss inherited memories of parental ordeals, such as the Dictation Test, imposed routinely on immigrants seeking citizenship. Although the concept of intergenerational trauma may not have been formulated then in the terms we recognise today, the phenomenon as such is nothing new. Trauma of various kinds is a dominant theme of this second, lengthy section, but equally potent is the desire and the will to overcome it, though not to forget it. Writing of it is a thread that leads out of the labyrinth of fear and powerlessness. In charting her own journey, Costi is reminding herself of where she comes from, where she has been, and in which direction her destination lies.

Moreover, in disentangling justice from the frequently obfuscating terminology of the Law, the poet/advocate is keeping alive her ability to respond, to act as advocate, in her own time of need and that of others, exercising the cultural concept of philoxenia (befriending the stranger), freeing her imagination so as to empathise and act effectively, in order to live her own life as she chooses and to offer support to others who are struggling. The physical form of many of the texts reflects the poet’s textual audacity and inventiveness; her clarity of thought; and the eclectic range of sources on which she draws in encapsulating the argument for justice, in ways and forms that capture the reader’s attention and stimulate reflection.

In the third section of the collection, titled “F(law)ed”, “The Heart of the Advocate”(46-7) frames in poetic form a particularly painful head-on encounter with the law. The outcome is implied rather than explicit; the three paragraphs of text are separated by the headings: “One word can change a truth into a lie”; “One doubt can change a truth into a lie”; “Justice must not be confused with law” and “Betrayal is harder to compensate than rape”. Needless to say, the story thus framed is a harrowing one. While the instances of individual victims of crime in these poems are actual (though not identified), based on cases familiar to the poet/advocate, they are representative of widely-perpetrated crimes (such as rape), and characteristic biases in the way the victims are perceived and treated by the judiciary, e.g. “She Will Not Parry” (48-9):

….

‘I put it to you madam that you wore that dress with intent

to arouse a hunger that was forbidden as we all know that

chiffon is a brazen fabric, not meant to be worn out in the

open. Your intention was for the incident to take place…’

(1954)

‘You have been known to embellish for attention, haven’t

you?’

(1996)

The poem “Crossing Over to Myth” (54-55) ends as follows:

My page becomes bow my pen becomes arrow

I aim for the Judge’s desk justice pierces through dust motes

transforms the wig’s tight ringlets

to spreading feather wings

Goddess Nike announcing

Acknowledge your bruising

Of a traumatised woman

Particularly biting (and witty) is “PLS (Principal Lawyer Syndrome)” (56-57),

which draws an imaginary trajectory between the empress Catherine the Great of Russia (1729-1796), derided for her physical imperfections, and “Katherine, who should have been made Law Firm Partner”, whose work ethic comes under scrutiny:

Two hundred years ago they stated that her face was a pity, her hips

were a berth, her marriage was porous and her lovers were countless.

In the 1990s, focus shifted to her work ethic, as young women out-

numbered young men entering the ranks of law firms. An enduring

role model was necessary for pin-up on the retina’s wall.

….

………………………. but it was me who went home while she

continued writing the brief for the partner.

While poetry is not new to advocacy, and advocacy is not new to poetry, these are poems for our times, reminding the reader (if that were necessary) that justice (and the system that supports it) is a work in progress, and that it falls to us, the uninitiated, to be discerning in order to decipher the truth amidst the legalese and procedural trappings of the courtroom, and to cultivate our capacities for compassion and advocacy in the domestic, social and professional spheres. Apart from which, this is a wide-ranging collection of fine poetry from a poet/ advocate who has honed her skills both as a poet and as a qualified and accredited member of the legal profession.

If, however, I were to choose a figure from Greek mythology (as Costi has done in several poems) with whom to associate this poet/ advocate, it would be the goddess Artemis: in ancient Greek religion and mythology, the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, transitions, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity; in later times, the personification of the Moon. Artemis as huntress, whose eye is unerring and whose aim, in countering injustice, is unswervingly accurate and unwavering.

© Jena Woodhouse

Jena Woodhouse grew up in Queensland, Australia, in the Capricorn Coast hinterland. Her professional occupations include teaching English as a Second Language; examiner for international tests of competency in English; book editor; arts journalist (in Athens,Greece). All have involved language/s, literature/s and writing. Her lifelong interests include archaeology, mythology, other cultures and their literatures (especially that of Greece, where she lived and worked for ten years); travel; protection of habitat and thenatural world; and writing. Her widely-published poetry and her fiction for children and adults have garnered a number of awards and honours, locally and internationally.

Angela Costi is a poet and writer with a background in social justice, law and community arts. Since 1994, her creative gatherings, including plays, short fiction and essays, have been published, produced, broadcast and translated. Her poetry collections include Honey & Salt (5Islands Press, shortlisted Mary Gilmore Prize 2008) and An Embroidery of Old Maps and New (winner of Poetry Prize in English, Greek Australian Cultural League 2022).