Live Encounters Poetry & Writing 16th Anniversary Volume Seven

November- December 2025

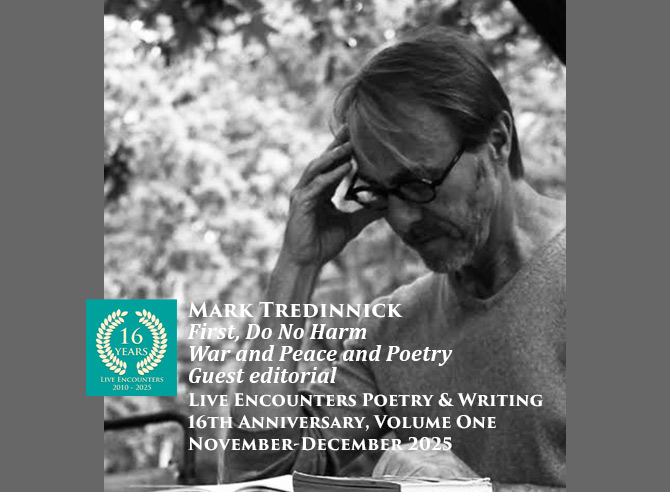

First, Do No Harm

War and Peace and Poetry, guest editorial by Mark Tredinnick.

First, Do No Harm

War and Peace and Poetry

The Clangorous Mechanics of What’s Real

Up in the northwest provinces of the great sandstone plateau we call the Blue Mountains, in southeastern Australia, a valley is cut by a small river that rises in the outlying ridges of the plateau, at Bogee, near Rylstone, and it flows, unaccountably (to me) eastward, into the bulwark of the plateau, to join the Wolgan and with that river make the Colo, which joins the Hawkesbury-Nepean, and, at last, they all find the sea. Just a bit to the north, and still in the stone country, the Cudgegong, another small river, which goes on to water Mudgee and to fill a couple of dams, rises to the east of the small river I’m sitting near, in its handsome valley, and yet the Cudgegong, though it starts further east, flows west—away from the plateau and the coast, and on into the hungry belly of the continent.

Few things in a human life or the life of the world or of a place run as simply as you’d imagine. The divide that runs a great crescent down the east coast of Australia, from Cape York to Gariwerd (the Grampians) and sorts the waters east and west of it, is made up of a thousand small and fractious ranges that find themselves tending somewhat unwillingly to cohere, and the notional divide from which the rivers flow either inland or down to the Pacific is as sketchy and erratic as all hell. As witnessed here at Glen Alice in the Capertee, where I am this late October among a profundity of birds and blowflies, wide pale pastures, and all these encompassing scarps, these handsome purple, ochre, grey assemblages. We’re here for a wedding anniversary (our first), and as I put it yesterday in a poem, a gift to my beloved:

The Drunkenness of Things Being Various

Here with me to read in the valley I have a selection of the poetry of Louis MacNeice, a selection for Faber made by Auden. “I didn’t think anyone was still reading MacNeice,” one of my students said to me recently, as if it were a reading list—somehow compulsory and drafted by whom and on whose authority?!—from which poets are periodically eliminated. There is only poetry. When it is well made it is, again, like the river, here, going on doing its work regardless of who cares to pay it any attention or attribute to it any value. MacNeice was not, perhaps, one of the great poets T S Eliot has in mind in some remarks I’ll get to in a moment. But then, who is? And who decides? But because, I think, MacNeice’s work was (and is) steeped so deep in craft and care for the human condition, less persuaded by some by the arguments of fashion, some of his work endures and is capable, movingly, of speaking truths about one’s own life and times, not just his.

Plus, as it happens, MacNeice’s time, which might have seemed to have passed, is here again. His star is rising. It sometimes happens. It happened to Bach, after seventy years lost to us all. Never trust fashion, I’d say.

Auden apologises in his short introduction for leaving so many poems out and for his lack of all authority except his likes and dislikes for making the choices he has. He also explains that MacNeice went through a long dull patch for a decade or so.

And the River Goes On

As I write that last paragraph, the wrens in their workshops inside the roses out the back give over to the chita chitas, notorious prophets of endings and beginnings, and then, as if to laugh me out of my quiet pieties, two little friarbirds (google them) overly the house brawling their hysterical plaints. Poetry should be hilarious and outspoken and even a little histrionic, sometimes, too. But its real work begins when the outcry subsides. And the river goes on.

The Drunkenness of Things Being Various

Here with me to read in the valley I have a selection of the poetry of Louis MacNeice, a selection for Faber made by Auden. “I didn’t think anyone was still reading MacNeice,” one of my students said to me recently, as if it were a reading list—somehow compulsory and drafted by whom and on whose authority?!—from which poets are periodically eliminated. There is only poetry. When it is well made it is, again, like the river, here, going on doing its work regardless of who cares to pay it any attention or attribute to it any value. MacNeice was not, perhaps, one of the great poets T S Eliot has in mind in some remarks I’ll get to in a moment. But then, who is? And who decides? But because, I think, MacNeice’s work was (and is) steeped so deep in craft and care for the human condition, less persuaded by some by the arguments of fashion, some of his work endures and is capable, movingly, of speaking truths about one’s own life and times, not just his.

Plus, as it happens, MacNeice’s time, which might have seemed to have passed, is here again. His star is rising. It sometimes happens. It happened to Bach, after seventy years lost to us all. Never trust fashion, I’d say.

Auden apologises in his short introduction for leaving so many poems out and for his lack of all authority except his likes and dislikes for making the choices he has. He also explains that MacNeice went through a long dull patch for a decade or so. And don’t we all. But the selection is still large and some fine poems made the cut: wonderful and wise “Sunlight in the Garden” and parts of the long poem sequence, “Autumn Journal,” in which the poet innovated free-verse and prose-poetic forms to establish a looser kind of structure for the sustained and grounded contemplations of love and ageing and place that he writes there. It’s clear what the poet stands against (cant) and for (beauty and honest and dignity and love and place. There was a lot to be anxious and angry about during MacNeice’s writing years: the threat of fascism, the threat of communism, the unbreathable air of London, the threat of nuclear extinction, the moral tightness of the times. But MacNeice knows that poetry’s part in the great work of resistance is the small work—the noticing how the big ideas that dominate a time play in everyday lives like of his own and in everyday moments. Like the sunlight on the garden in the poem that observes it: a poem of hope and despair, at both public and private loss, a quiet observation of the persistent beauty of things, notwithstanding ill winds.

It is only with the great poets, perhaps, that the language of the poet escapes the privacy of her idiolect and interiority and transcends the habits of mind and speech that characterised her times. More on this proposition (Eliot’s) in a bit, but just to say there are, for me, a few too many occasions where I trip up in MacNeice’s utterance and wish he had found the courage to be plainer or worked out how to shake a personal or temporal habit unlikely to help the poem survive its moment. (In such moments one hears but barely comprehends the speaker, and one is shut out a little from the moment of Being that had seemed, till then, one’s own, all of ours.) Even in the poem “Snow,” which I love, I meet a little unhelpful opacity. But then there are these lines—lines as radically clear and hilarious and serious and important now as then, as vital for us to understand as readers and voters and writers now as these lines always were: for it is true, I think, that prevailing discourse (political, intellectual, artistic and private) tends to bifurcate and enmify and oversimplify or overcomplicate and to strip lived experience of its layers and contradictions and eros and dynamism.

World is suddener than we fancy it.

World is crazier and more of it than we think,

Incorrigibly plural. I peel and portion

A tangerine and spit the pips and feel

The drunkenness of things being various.

Poetry’s Innate Activism: Bearing Implacable and Memorable Witness

Please let us—in our languaging (as in his) and in our understandings of how humans are and how relationships play and what things mean—recall and practise the incorrigible plurality of things, the drunkenness of their and our own being various. Let’s leave the platitudes and stereotypes and categories to AI. Let’s leave the mantras and slogans and tribalism to commerce and politics. Poetry’s activism is performed by its bearing implacable and memorable witness to the real, in language that does deep justice to what it witnesses—place, moment, person, cause. Good poetry keeps doing that justice long after the news cycle has moved on; its justice lasts, transcending as it does the particulars of the times it witnesses., Poems work in time, but also in eternity. Writing poems is for finding, through care with language, one’s own unique range of variousness and for divining one’s own plurality (for coming back plural, as Rumi put it once), and for making common cause—through language as awake as this head of the valley is with layers of being, past and present—with the issues and moments and instantiations of the moving world, as the world manifests in given faces and places and beings and schemes. Poetry is for joining the wide world of Being It is for perpetuating the uncanny and beautiful, and sometimes unbearable, variousness of things, catching them in the act of getting after their living, each of them refusing, notwithstanding all that is hard and wrong, not to Be.

Toward a Poetry of Peace

All is not right with the world.

It never is, but things right now, in many arenas, are unhappy and dangerous, terrifying and ugly. Mobsters broker what they like to call peace; the idea of the public good, the common good, has flown from minds both left and right; kindness and forgiveness and generosity are vanishing from heart and mind and mouth; the oceans warm and the plastics swill and the forests fail and the cities burn; loneliness is pandemic; civil disagreement, on which democracy depends, has largely descended into shrillness and name-calling, a mutually assured destruction by competing outrage; all our thoughts are thought for us and all our phrases fashioned by bots using stolen IP; ignorance informed only by internet rage gets despots elected, most of whose work, as ever with despots, is vengeance and rank ideology and the further enrichment of the rich.

It is easy to despair, but one must not, or all that isn’t right prevails.

What might be the role of poetry in times of such trouble and injustice? Not, I’m certain, to engage in the devices and postures of prevailing politics: the anger, the name-calling, the categories of blame and cancellation, the tribalism. In order to save us from the politics that prevail—and not only among politicians—poetry, I believe, must practise, in its rhetoric, its diction, its devices, and what it chooses to speak of, the values of dignity and compassion, tolerance and mercy and peace and courage and grace and civility that are so missing from the hegemonic discourses that rule our institutions of government and law-enforcement, of public policy and education. Remember Heaney, who had to fight hard for what it took to know the truth of what he said in accepting the Nobel Prize: poetry, uniquely, caters for two contradictory needs of the human spirit in times of trauma—not only a retributive, profoundly honest truth-telling, but also, a softness of seeing and saying, without which the traumatised soul, though their suffering be names, is still lost and without love.

Let us not forget to love: the world, in its woundedness; each other, and yes, even our enemy. Poetry is the way love speaks: tough love, soft love, the slim and persistent stream that defeats, in the end all resistance.

Poetry’s work is to keep us from despair, to call us to turn our pain and anger into something more useful. Poetry refuses to accept or to allow us to accept what the politics of greed and envy and revenge ask us to accept as real. Poetry’s politics is its refusal of the idiom of politics—its vow not to act and think and speak the way that tribal politics, sects, and ideologues do. Its work is to make us always more human than we are told we are. To love us in our frailty and magnificence and to ask us to be kinder and to be more useful to each other.

Softer Bombs

How a poet might respond to what Israel, for instance, with Western weapons, has done to Gaza: here is one of the great moral challenges of our moment. And in one sense, the response is easy. Anyone inclined to read and write poetry will contemn the murderousness, the depravity, the vengefulness, the asymmetry, the barbarism of the occupation and destruction (just as the bloodthirsty violence of Hamas, which, rising though it did from years of occupation of Palestine by Israel, triggered the monstrous and disastrous Israeli response).

But how to make one’s words useful to anyone, especially anyone under the bombardment, or to anyone making decisions that might bring an end to the killing. That is the real question. Poems of shrillness and (understandable) anger have prevailed, but it’s not clear how much they help anyone except as a catharsis for the speaker. It is too easy to write a poetry violent and intolerant in its attitudes and language. But no one needs more violence. Entrenched tribalism is the problem here; enmification on the page perpetuates war; it heals nothing and no one.

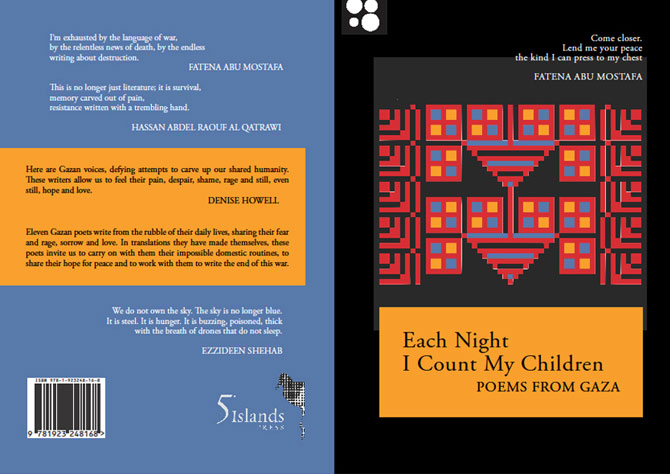

A fine young Gazan poet, Fatena Abu Mostafa, puts it this way in one of the poems gathered into an anthology by Denise Howell, Each Night I Count My Children: Poems from Gaza, a book we’re proud to have just published at 5 Islands Press:

I’m exhausted by the language of war,

By the relentless news of death, by the endless

Writing about destruction …

Come closer.

Lend me your peace—

The kind I can press to my chest.

There is poetry’s work, spoken of by one under the bombs, one whose poems speak the language of peace even though there’s a lot of war in them. There is our work, I think. There is the politics of the poem. To let us feel, in our selves, what the war is and what the dying and the suffering are and to insist on more from ourselves and our friends and leaders. The work of peace is poetry’s work.

All That War is Not: How to Write Poems of Use in Times of Violence

For poetry refuses and softly refutes the violence of dehumanising discourses: war, fundamentalist ideology, absolutist politics, the words with which one tribe, in any context, steals humanity and variousness from the other. That is its politics, and it happens to our hearts. Poetry does not enmify; it takes life’s side; it knows no idiom of revenge.

Poetry over the centuries has borne witness to what being feels like and what it may mean to live a finite life in an infinite universe, especially when the living is hard: as it is for the poets in this book, women and men and children carrying on under unrelenting siege in Gaza. Poetry restores dignity to death and sorrow and bitterness and abjection, to hope and survival and daily bread and to carrying on notwithstanding. It divines what is human, and therefore sacred, in moments particular to those who suffer (or are blessed by) them, and it invites us (readers) to know those moments as our own.

Good poems implicate their readers; in a sense, they turn the reader into their subject. This is the work of metaphor and speech music and form. The deeper speaking of poetry.

From often unbearable, chaotic, ecstatic or unimaginably awful eventualities, from suffering and privation, poetry fashions—in the voices of those who survive those moments—habitable forms, beautiful coherences, in which hope is possible again and violence falls well short of its aim. A poem is a soft bomb. A small incendiary device, a poem goes off and doesn’t stop; but its work, unlike the bombs raining on Gaza, is to give life, not to take it, to dismantle ignorance and unsettle apathy, to transfigure rage into something more useful, to practise and engender compassion, to implicate the reader in both the cause of the trouble (or delight) and in its consequence and in the possible futures the poem helps us imagine.

A good poem, like all the remarkable pieces we included in the book Each Night I Count my Children, recruits the reader to help “write the ending” of this and every war.

Wars pursue and depend upon ideological abstractions (ideas about victory and homeland and enemy and patriotism and vengeance and so forth); they cheapen life in order to take it and to make that okay. Poetry should be all that war is not—innately human, relational, particular, contradictory, various and generative. A poem is not just a bullet; it is a mother and a father and a hearth and something unendurable to endure. It is despair seen off and tyranny stared down. It is a voice that loves life, even when it condemns those who take it.

The poems we were proud to publish in Each Night are partisan for peace and for life and for mothers and fathers and children. For hope and home. Even if you forget the circumstances under which they’re written, they are remarkable instances of poetry’s peace-making work, its soul-making, heart-breaking, mind-altering work: the way it has kept humanity (each of us and all of us) sane, made sense of senselessness, taught readers to find their own selves in the faces of the enemy (and the enemy’s victim), to love better for being implicated in both the violence and the resilience. These poems count their children, name their dead, remember the sky and the ramshackle city by the sea; they feed the cats, laugh at calamity, despair and keep going; they give in and cry out and find a way to wake again and refuse to fall silent. They throw soft bombs. They restart the revolution in the heart, which does, in the end, write the end of war.

A poem cannot stop a war; a book of poems won’t bring about a peace. But still a book of peaceable poems can save lives by telling them and honouring them and those like them (many of them already lost), and it can help a beleaguered community by moving readers in a position to help, to help. Apart from reaching the readers Denise’s book has already and reached, the book, through her generosity and that of my colleagues at the press, who gave their time for nothing and donate all takings to the work of MSB in Gaza, will be of some practical use. As all poems should, I reckon, try to be.

First, Do No Harm

Doctors, before they practise, take the Hippocratic Oath. First, do no harm: this is that oath, or the heart of it. Hippocrates ( c.460–370 BC), to whom the oath is attributed, was a physician and philosopher from Kos, and although it is from his writings and that of the school of Epidemics he founded that the oath came, his words do not anywhere quite say “first, do no harm.” They say “I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm.” And they say “Practise two things in your dealings with disease: either help or do not harm the patient.” But the idea is the same: the primacy of refraining from harm in offering help—in meeting the medical needs of those you serve. And so over time, in the Latin phrase “primum non nocere,” and in the English “first, do no harm” settled into popular usage, though not in so many words, among medical practitioners (The world rarely runs exactly or as simply as it seems.) It is a form of words that all of us, even poets, know, but few of us, especially poets, pay enough attention to in our work.

Clearly the oath is not a promise that no patient should ever feel pain; the central idea, vital to the humanity of the practise of medical care, is that nothing the doctor does should be done for any reason other than to heal, to help the patient with their need. Something a doctor does, a surgery for instance, may hurt, but it must always aim to heal.

Interestingly, other versions of the oath doctors take remind the doctor that they treat a whole human (and indeed their family) and that the soft skills of the physician, like kindness and honesty and attention and the gentleness of the doctor’s speech and action, matter as much as scientific considerations in the practise of care. Not to play God, and not always to presume to have the answers.

Now, poetry has been important to all the human cultures we know of, and poetry has been associated in most, if not all, of them with healing work: it is for soul-making, said Keats; it is for survival, wrote Orr. There is no question readers have through the ages turned to poetry to find themselves accompanied in their pain or ecstasy and to help them make sense of the incomprehensible, to find a way through difficulties of the hearth and the mind and spirit.

So, if there were still, as I hope there is, a shared understanding that poetry ought to be spiritually or psychologically useful, even healing in some way—to make (and for the reader to find) in words a habitable coherence where before there was just trauma or a chaos of emotion—then the poet might want to take seriously the work she or her makes, the medicine they offer to the world. In which case it is worth asking what an oath like “first, do no harm” might look like for a poet, and whether it might help us find our readers, and help them, again.

If a poet were asked to take an equivalent of the Hippocratic oath before making a poem, it might, I reckon, have these dimensions.

- First, to help. Not just to voice, but to meet human needs for language that heals and elevates our understanding of being alive in a troubled world; that makes readers kinder and braver and less afraid and less full of ourselves.

- Also to cause no harm to language or person, while throwing light or bearing witness or consoling grief, or giving delight, or recasting the spell (as Emily Dickinson put it), or however it is one thinks one’s words might help (the language, the world, the imagined reader, the general stock of wisdom, the moral clarity of one’s times.

- To treat, as it were, the wholeness of the person (the reader), not just her intellect or his politics or their sociological or anthropological or cultural category, but their being, their incorrigible variousness, their drunkenness of variousness.

- To arise from one’s whole self, at one’s best and fullest, not merely in one’s professional life or social category. To write, as Montaigne once put it, as “all that I am.” Out of one’s flawed and mysterious and various humanity.

- Not to play god: never to be too certain of one’s observations or categories or mantras or prescriptions, one’s understanding of who is victim and who is perpetrator, of who is right and who is wrong. To be aware of the terrible complexity of things, and yet to be clear in one’s values, partisan always for justice. Poetry, after all, forgives us for being human, and finds us all both culpable and innocent and in need of some care.

- To honour the obligations a poet owes, not just to their own people and readers, but to the future and the past, and in particular to the great long tradition of the making and sharing and private reading of poetry, the deep importance of that tradition to the wellbeing of human societies and to individuals in those societies. This is not just diverting hobby, in other words; nor is it a microphone and a mobile phone and a chance to hurl curses and opprobium at the bad and the ugly; poetry is a gift given to you to put to work for others, to rekindle the revolution in their heart).

T S Eliot, Dante, and the Poet as a Servant of Language (and its Readers)

Asked to make a lecture on Dante, Eliot wrote an essay, instead, that walks around the ways The Divine Comedy and its poet had touched and influenced him—in life and in letters. Such is my affection for the great Italian poet, we named a dog for him: Dante, the golden cocker spaniel, for whom the straight way was always lost. Jodie and I read our way through Dante during COVID, sharing the Italian in our best imitation of how it might have sounded, and moving between Sinclair’s prose and Sayers’s metrical poetic translation, and checking also, when her meter got in the way, more recent translations that attempt to catch the poetry but not to imitate all the poetics, and that time in our lives, though the going is not always easy and the divinity not always all that comedic, will remain one of the times of our lives.

Because this short trip to the Capertee is a celebration of our first wedding anniversary, Jodie brought with her the book in which Eliot’s essay “What Dante Means to Me” appears, and two days ago she read it aloud over breakfast. In her voice was Eliot’s voice and inside his, Dante’s old Italian, and here and there some Shelley. Or not their voices, but the music of their intelligence and craft and the humanity they witnessed.

I can’t claim to be either as steeped in Dante as Eliot was or as deeply influenced by him, though it stays with you, that musical intelligence, that imagery, the humour and the rhythm of the wisdom. I’m with Eliot when he writes that there are some poets, he calls the masters, “to whom one slowly grows up.” I’d tried Dante a few times in my thirties and forties, but I think I was only ready for him, in my reading and craft and in my living, in my fifties. Eliot was largely wasted on me at school, too; I’d grown into him by thirty-three, and largely out of him by fifty, but his ideas—the objective correlative, the power or rhythm, individual talent and the poetic tradition—stick with me.

And so it is that Eliot’s three conclusions about Dante feel like better ways of saying things I have been teaching and preaching and trying to practise for over fifty years. I have no doubt that, like Sappho and Dickinson and Shakespeare and Auden and Rumi and others it is perhaps too early to be sure about, Dante was as masterly a thinker and world-builder and, above all, an artist of the line as anyone ever. It may be, as Eliot says, that though many poets are wonderful, and we need every one of them, but only a few are great. And to the great artists (Hannah Arendt says the same of Auden, by the way) Eliot attributes three particular qualities. I’m not sure it helps much these days to speak of masters and others. Certainly, though, the qualities Eliot touches on in Dante would be useful for all of us who write to work at.

And it seems to me we’d win our readership back and show the world how useful and necessary poetry can be, if we valued and attempt to practise these values and skills.

- “The great master of language,” writes Eliot of Dante, “should be the great servant of it.” Through sustained attention to one’s craft and to one’s language, the great poets do, writes Eliot, and the rest of us should, use the language, whichever is ours, in its fullness, to serve it by stretching and renewing it—but not mostly by innovation or personal eccentricity, by ignoring its ways or subverting or abusing it. The language we write in comes to us as a great gift, I’ve often thought, and we ought to earn that gift, that privilege, by the love and care with which we employ it, by adapting ourselves to it as much as it to us, by fitting it thoughtfully to our times and the needs of our readers in our times. Let’s aim, in other words, not to fuck language up in the service of our ambitions, but to leave it at least as rich and wide and fine as we found it. First, in other words, let’s do no harm, and beyond that, to do some good to the language and somehow ennoble it and enable it to reach out in its native wealth to more readers than would have been the case without us, so that the language, as it finds our readers through our poems, to do some radical good.

“To pass to posterity one’s own language,” Eliot says, “more highly developed, more refined, and more precise than it was before one wrote it, that is the highest possible achievement of the poet as poet.”

- The poet, Eliot would say the great poet, has the gift, or develops the art through practices of inward and outward attention of wider and deeper and more discerning apprehension of the phenomena in which the world plays out and one’s own life and the lives of others play out in it, experience existence in its many forms and colours.

The poet notices more shades and “vibrations,” as Eliot puts it, of lived experience. And the poet will be good or great to the extent that they have the natural gift—or train themselves by apprenticeship, reading and practice—of finding within the language to which they have access ways of saying that do justice to that wider range of perception and deep and more subtle range of thought that is the core practice of the poet.

And so, as Eliot notes, the first gift or genius (linguistic accomplishment, craft, the practised mastery of the language in its semantic and lyric, figurative and musical realms) serves the second (seeing and feeling and thinking more fully). So the poet who would write some poems of use will see deeper into how life plays out, into the heart of the “incomprehensible” or mysterious or mystifying or terrifying or ecstatic, and they will offer a response to the plurality of what they apprehend, that in its sheer adequacy, in its mastery of language and poetics, serves its material more faithfully and invites a reader more fully into a comprehension of the incomprehensible, into an experience deeper than they had known they could have, or into an understanding of a phenomenon of living that a reader had known but hardly understood—and now does.

One of the ways good poetry serves us all is to expand the emotional, phenomenological range and literacy of those who read it, and of the cultures, at large, in which that poetry finds its place. This, it seems to me, has been the work—help with allowing us more fully and usefully and safely to feel and know and survive sanely the kinds of trouble and delight every life bumps into—that poetry has performed through the ages. And it is the work readers expect it to do. So, when much of the poetry readers encounter fails either to notice profoundly or speak of what it meets with well (remarkably, but clearly), to speak of it, even half to sing of it, not merely to think or rage about it—they lose their faith in poetry.

- Dante, Eliot observes, writes from where and who he is—his times, his place, his language, his culture, his nature—but somehow, at the same time, he speaks about and speaks to all times and all places and all languages and creeds and genders and ways of being. Dante is, Eliot intones, the least provincial of poets, but “he did not become the least provincial by ceasing to be local.” The Irish poet Patrick Kavanagh wrote that the parish was the proper province of the poem. “To know fully even one field or land is a lifetime’s experience,” he wrote. He understood the parish not as place or worldview that shut out or denied the world, but as an “aperture” through which, alone, the world might be seen and known and named. Depth, he wrote, not width, is the work of the poem.

Eliot does not spend much time on this point in his published talk; perhaps he ran out of time. But I would say that the trick here is to know your moment as an instance of all such moments, this war and suffering as instances of all such traumas, your place as one incarnation of the world, not as if it were the world, let alone the best or worst place in it. History, the poet understands, is made of moments such as these, and she writes in that knowledge, offering up the world near at hand, the bird, the love affair, the loss, as an instance of all such phenomena everywhere and any time. Dante, for Eliot, and it felt like that to me reading the Commedia, has that knack. All that Dante’s poet encounters in hell and purgatory and paradise, though peculiar to times and ways now lost on us, seems spoken in one’s own voice and seems to happen to oneself— now, in whatever analogous circumstances one finds oneself in. There will always be lessons in a good poem for the times and troubles the reader lives in, far away though she is in time and place, from the time and place the poem witnesses. The good poet knows that it is not herself she writes, but all such selves, ever, and anywhere.

How the Poets Have Run Themselves Out of Town and How They Might Run Themselves Back in Again

We find ourselves in times that need poetry more than they know. And just when it is needed most, poetry, for most of the people who need it, is hard to find and harder yet to fathom or put to much use. For one thing, poetry plays much less central a role in most people’s lives than it used to—than it should. This is true especially across those parts of the world where English is the dominant language and where late-stage capitalism is in the ascendancy. By contrast, it struck me, reading the poems Denise Howell sent me to consider for the anthology—poems written by teachers and doctors and nurses and students and psychologists, by mothers and fathers, and in some cases “professional” poets—how much accomplishment in craft and perception and articulation were on display, suggestive of people more steeped in a long tradition of poetry than is true of most of us who speak our lives in contemporary English, most of the people, including book-lovers and teachers and students, that I encounter in my native land.

I don’t want, here, to rehearse the many reasons for poetry’s flight from the centre of our values and days. Some of the reasons are what the economists call exogenous, beyond readers’ and poets’ control (the radio, popular music, the internet, aesthetic theories that forgot to take readers along with them, television, the ascendancy of film …). But we poets who mourn our falling sales, the absence or the slenderness of poetry sections in most bookshops, the lack of media attention to poetry, the lack of poetry literacy, would do well to look at ourselves and the practice of our art. This, too, is a big story, but since the dawn of modernism, the coming of free verse, the rejection of form (of meter and speech music and rhythm structures and often, too, the rejection of punctuation and syntax, the refusal to make sense), the story of poetry is its turning from its readers; it is the story of its refusal of the role it has played and plays still in many cultures—the making of memorable sense of mystery and tragedy and delight, of being of some use. The story of twentieth and twenty-first century poetry in the west is two divorces: from its readers and their needs (for clarity and delight, the work of lyric sense-making poems from the dawn of human languages have fulfilled), and from language and its service, at its best, of our deepest human needs, as I’ve explored them here.

Poetry has largely in our times uncoupled itself, with the support of wave after wave of theory, from the tradition of (oracular, arresting, strange, memorable) sense-making by means of form and speech music and of patterns of syntax recognisable to most readers.

There are many exceptions, of course, many poets even in recent times, like Seamus Heaney, Mary Oliver, W H Auden, Judy Beveridge, Joy Harjo, David Brooks, who have kept the poet’s oath to language and readers and the healing of spiritual harm, through devices of language used at its most economical and stirring. But poetry has lost its readership, has lost the greater part of its market; its brand awareness, as the commercial people say, is fading, readers are out of touch and out of love with poetry, suspicious of it, and that is a tragedy. A tragedy very largely of poetry’s own making. This is not really something that has happened to poetry. Forgetting whom and what they serve, persuaded by one theory after another that has elevated thought over language, the idea over the utterance, the poet over the reader, the poets have run themselves out of town.

Time to find a way back in. Manifestly, no one can live long in a world from which the lyric has taken flight, where daily discourse is violent and stupid and brutal in ways that any good poem would sing right out of town.

© Mark Tredinnick

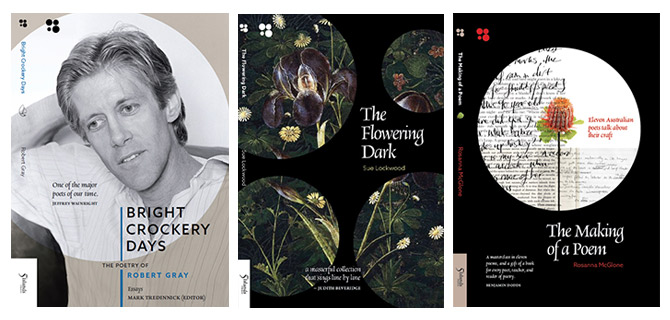

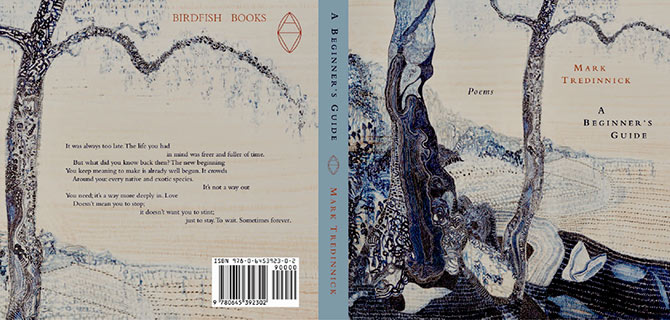

Mark Tredinnick OAM is a much-awarded poet and essayist and the managing director of 5 Islands Press. He is the author of five collections of poetry, including, most recently, A Beginner’s Guide; Chain of Ponds: New &: Selected Poems appears in July 2026. Next year also sees the reissue of his classic guides to the craft:The Little Red Writing Book and The Little Green Grammar Book (New South). Mark lives with his wife Jodie in Bowral, on Gundungurra Lands, southwest of Sydney. He runs the poetry masterclass What the Light Tells online through his website https://www.marktredinnick.com/ and he teaches literature and creative writing at the University of Sydney. He is at work on The Divide, which tracks the Great Dividing Range in prose and poetry, the way Basho’s Narrow Road tracked the deep north/ outback/ deep interior of his times. 5 Islands Press has recently published a collection of poems from Gaza, Each Night I Count my Children, edited by Denise Howell. All revenue goes to support MSF in Gaza. Please support the book, which you can purchase at https://www.5islandspress.com/