Live Encounters Arab Poetry & Writing 16th Anniversary Volume Five

November- December 2025

Echoes from the Nile: The World of Ancient Egyptian Poetry,

guest editorial by Dr Salwa Gouda.

The prevailing image of ancient Egypt is one of monumental silence: the stark geometry of the pyramids, the stoic sphinx, the towering temples of Karnak standing against the relentless sun. These structures of eternal stone speak a language of power, divinity, and the immutable cosmic order of Maat. For centuries, our understanding of this civilization was filtered almost exclusively through these official channels—the funerary spells of the Pyramid Texts, the elaborate guides of the Book of the Dead, and the hymns carved for gods and pharaohs.

These texts are profound in their scope and purpose, but they inherently represent the voice of the state and the priesthood, literature concerned with eternity, the afterlife, and the metaphysical maintenance of the universe. However, if we attune our ears to a different frequency, a quieter, more delicate and profound human sound echoes from the papyrus scrolls and inscribed limestone flakes that have survived the millennia. This is the vibrant, often overlooked voice of ancient Egyptian poetry, a rich literary tradition that serves as the essential counterpoint to the civilization’s monolithic grandeur.

It reveals a people not solely preoccupied with death and divinity, but one deeply in love with life, nature, and the intricate, often tumultuous landscape of human emotion. This poetry proves that the architects of eternity were also passionate, witty, vulnerable, and introspective human beings, whose inner lives were as complex and vibrant as their architectural achievements.

This significant shift from purely sacred and functional texts to a more personal, lyrical literature marks a fascinating evolution in Egyptian culture. The Middle Kingdom (c. 2050-1650 BCE), often hailed as Egypt’s classical age, saw the stabilization of the state and a flourishing of arts and letters that began to accommodate more reflective themes. However, it was during the prosperous and confident New Kingdom (c. 1550-1070 BCE)—an era of imperial expansion, international trade, and a growing, literate class of scribes, officials, and skilled artisans—that this personal voice found its full confidence and widespread expression.

A society with more leisure and a broader base of literacy created an audience and a patronage system for a new kind of expression. This was a literature composed not for the tomb, but for the garden; not for the god in his sanctuary, but for the beloved in one’s arms; not for eternity, but for the fleeting, exquisite present. The most captivating and accessible of these works are, without doubt, love poems. Discovered on precious papyri like the Chester Beatty I and on informal ostraca—the pottery shards and limestone flakes used as the notepads of the ancient world—these verses feel startlingly modern in their immediacy and emotional honesty.

They are not the formal declarations of state or the structured rituals of later European courtly love traditions. Instead, they are the raw, playful, agonizing, and intimately relatable whispers of lovers, their voices bridging a chasm of three thousand years with effortless grace.

The poets of the Nile Valley employed their lush, life-sustaining environment as their primary artistic palette. They perfected a technique like what would later be known in Arabic poetry as the wasf, or descriptive blazon, to paint meticulous portraits of their beloveds using imagery drawn directly from their world.

A lover is never simply beautiful in an abstract sense; she is intimately woven into the very ecosystem of desire and admiration. In one famous example, the poet says: “My beloved is like a gazelle, / Whose limbs are sleek, / whose neck is long, / whose hair is dark. / I hold her fast, I will not let her go, / that I may place her in the house of her mother, / with the door shut behind us.” The choice of the gazelle—a creature synonymous with grace, alertness, speed, and wild, untamable beauty perfectly captures the essence of a desired one who is both captivating and elusive. The concluding lines are equally significant, expressing a yearning not for illicit passion, but for private, sanctioned intimacy within the “house of her mother.”

This reveals a sophisticated understanding that for all its overwhelming power, this passionate love was experienced within a real, structured world of family, social codes, and domestic expectations. The goal was to bring the wild gazelle into the social fold, to legitimize the passion within the framework of community.

In this sophisticated tradition, love is never portrayed as a mild affection but as an all-consuming, physical and psychological force that recalibrates the very being of the lover. The natural world is rarely a passive backdrop in these dramas; it is an active, sympathetic participant, a chorus commenting on and amplifying the human emotions played out at its center.

This is most powerfully expressed in the pervasive theme of “lovesickness,” a condition so severe it is presented as a physical ailment that defies the finest medical care of a civilization renowned for its physicians. A lover laments with palpable despair: “Seven days since I saw my beloved, / And illness has invaded me. / My body has become heavy, / I am forgetful of my own self. / If the chief physicians come to me, / My heart has no comfort of their remedies… / What will revive me is to say to me: ‘Here she is!'” This explicit and poignant dismissal of Egypt’s renowned medical science is a powerful rhetorical declaration.

It strategically positions love as a condition of the spirit and the emotions, an existential malady whose only true antidote is the tangible, physical presence of the beloved. This theme of lovesickness is also rendered with charming cunning and a touch of humor in other poems, where a young man feigns illness to lure his beloved to his bedside, knowing full well that she alone holds the cure to his fabricated, yet emotionally real, distress.

The profound pain of separation is often expressed through a direct, plaintive dialogue with nature itself. In one particularly moving poem, a lover addresses the dove, the herald of the dawn that cruelly ends a precious night of union: “The voice of the dove is calling, / it says: ‘It’s day! Where are you?’ / O bird, stop scolding me! / I found my love in his bed, / and my heart was overjoyed… / My hand is in his hand, / I walk in dance with him…” Poems from a female perspective, such as this one, are often rich with social and emotional nuance.

The dove is transformed from a neutral symbol of peace into a chiding, unwelcome intruder on intimacy. The private, authentic joy of the night is starkly contrasted with the public performance of the day, where the lovers must walk in a social “dance,” their relationship now subject to the gaze and judgment of the community. The speaker finds her ultimate validation not just in the secret consummation of love, but in the prospect of being publicly acknowledged, a status that formally protects her from the vulnerability and potential heartbreak of being a mere secret.

These poems were thus not only pure expressions of emotion but also sophisticated navigations of a complex social world where public honor and private desire were in constant negotiation.

Running parallel to this intimate, secular tradition was the continued flourishing of the religious hymn. These works, while more formal in structure and purpose, are nonetheless masterpieces of poetic metaphor and awe-inspired observation, seeking to give shape to the formless and a voice to the ineffable.

The sun god Amun-Ra could be envisioned as a falcon soaring across the vault of the sky or a mighty ram whose breath gave life to the entire world. The great Hymn to the Nile personifies the annual, life-giving flood as the god Hapi, a force of benevolent chaos and creation whose arrival meant “the poor and the rich are laughing, / the trees and the vegetation are verdant.”

The pinnacle of this sacred poetry is undoubtedly the Great Hymn to the Aten, attributed to the pharaoh Akhenaten during his revolutionary monotheistic reign. This hymn is a masterpiece of world literature, notable not just for its radical theology but for its intensely intimate and joyful portrait of divinity. The sun-disk Aten is not a fearsome overlord but a benevolent, nurturing presence; its rays are repeatedly described as “hands” that “soothe,” “caress,” and embrace all they touch.

The hymn is a breathtaking, almost scientific catalogue of the world awakened by the sun, and it reveals a remarkably global and inclusive consciousness: “How manifold are your works!… The countries of Syria and Nubia, and the land of Egypt; You set every man in his place… Their tongues are diverse in speech, and their natures as well; Their skins are different, For you have differentiated the peoples.” This focus on the tangible, visible world—from the chicks in their nests to the diverse cultures of humanity—creates a powerful bridge between the divine and the everyday, mirroring the same keen, loving observation of nature that animates the secular love songs.

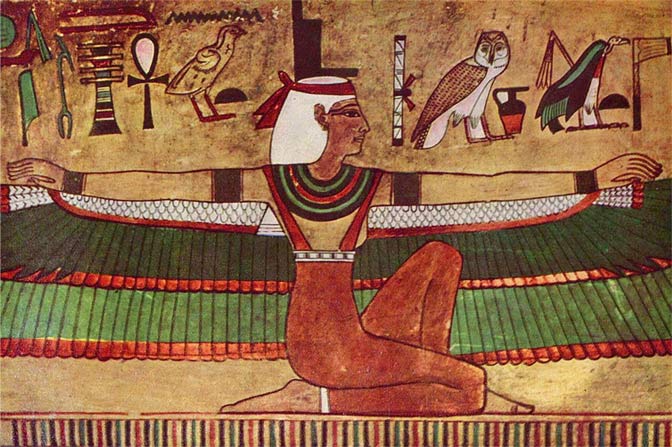

The figure who most perfectly embodies this seamless connection between the divine and the human, the cosmic and the personal, in Egyptian poetry is the goddess, Isis. In grand temple hymns from the Late Period, particularly at her great cult center at Philae, she is celebrated as the universal mother, “the Great Magician, the Queen of the Gods” whose power and scope transcend Egypt itself.

Yet, her most resonant and poignant poetic role is rooted in the foundational mythology of Osiris. Here, she is not a distant, omnipotent deity but a vulnerable, intelligent, and fiercely determined individual using her wits, her courage, and her formidable magical prowess to restore her murdered husband and shattered family. Her laments for Osiris are among the most powerful love poems in the entire Egyptian canon. In these texts, she is the archetype of the grieving widow and devoted wife, a figure of profound pathos.

This narrative of unwavering loyalty, desperate search, and magical restoration made her an immensely sympathetic and accessible archetype for universal human experiences of loss, devotion, and resilient hope.

It is no surprise, therefore, that her influence directly infused the secular love songs, creating a fascinating synchronicity between religion and daily life. In the Chester Beatty Papyrus I, a young lover swears: “I love you; I choose you before all others… Let me not be forced to swear, ‘By the beautiful Isis!’ lest I take my oath in your name. Come to me, that I may see your beauty!” Here, the poet brilliantly uses the immense cultural and religious weight of the Isis myth—her legendary, unwavering fidelity—to underscore the depth and absolute seriousness of his own human passion.

To swear an oath by Isis is to invoke the ultimate standard of devotion; to do so frivolously would be a sacrilege. The lover’s fear is that his feelings are so profound that any oath would be true, binding him eternally. Through this divine figure, the sacred hymn and the secular love poem are revealed as two complementary expressions of the same fundamental, world-shaping power: the force of love and fidelity, whether directed toward a god or a mortal beloved.

To fully appreciate this poetic tradition, one must mentally reconstruct its original context as a primarily oral and social art form. It was meant to be performed, not just read. Poems were sung or recited to the melodic accompaniment of harps, lyres, and the rhythm of tambourines and sistra during festive gatherings in the lush gardens of wealthy estates or in more modest communal settings.

The very structure of many poems, featuring call-and-response patterns or dialogues between groups of young men and women (the chorus of youths and maidens), points directly to their performance at banquets, harvest festivals, or other social celebrations. The archaeological discovery of these texts at Deir El-Medina, the village of the royal tomb-builders, is particularly telling. It provides incontrovertible evidence that this lyrical expression was not the sole province of the elite scribal class or the royal court.

The highly skilled artisans who carved the pharaohs’ eternal resting places in the Valley of the Kings scrawled these very love songs on the limestone flakes and pottery shards they used for practice sketches and memos. This is a profoundly poignant symbol of the enduring human need to express love, joy, and beauty—a need that persisted and flourished even in the direct shadow of the death-obsessed monuments they were commissioned to build.

Furthermore, the Egyptian language itself was a key tool in the poet’s arsenal. Its root-based system and remarkably flexible syntax were perfectly suited for the layered meanings, puns, and evocative metaphors that characterize great poetry. A word for “heart” (ib) could simultaneously imply “mind,” “will,” and “understanding.” The simple act of “entering a garden” could carry unmistakable and powerful erotic connotations. This inherent linguistic richness allowed for a density of expression, a resonance of sound and sense, that is often largely lost in translation, reminding us that what we read today is only a faint, ghostly echo of the original’s full musicality and semantic complexity.

Ultimately, the poetry of ancient Egypt compellingly shatters the long-held, simplistic image of a morbid, death-obsessed culture. In its place, we find a people who were keenly, lovingly observant of their environment, who celebrated the body and its senses without shame, and who understood love in all its forms—erotic, familial, divine—as a powerful, disorienting, and ultimately life-affirming force.

They gazed at the same vast night sky that inspired their grand cosmologies and saw in it a metaphor for a lover’s flowing hair. They felt the same blazing sun that empowered their king as a god and felt its warmth as a personal, nurturing embrace. The names of these individual poets are almost entirely lost to history, subsumed into the collective, anonymous voice of their culture. Yet, in the delicate, graceful lines of a love poem scrawled on a shard of pottery destined for the midden heap, or in the majestic, soaring verses of a hymn carved into a sunbaked temple wall intended to last for eternity, they achieved a different, perhaps more profound kind of immortality. They proved that the most lasting monuments are not always made of stone.

The most enduring are woven from the simple, yet eternal, materials of words that capture the timeless rhythms of the human heart—its passions, its wonders, its sorrows, and its eternal, joyful conversation with the world. In their poetry, we do not meet a dead civilization, but living, breathing, feeling voices. In listening to them, we recognize a part of ourselves, connected across the immense gulf of millennia by the universal and shared experiences of love, longing, and the sheer, unquenchable awe of existence. This literary legacy is their true and greatest pyramid: an invisible, indestructible structure built not from quarried limestone, but from the enduring material of human emotion.

© Dr Salwa Gouda

Dr Salwa Gouda is an accomplished Egyptian literary translator, critic, and academic affiliated with the English Language and Literature Department at Ain Shams University. Holding a PhD in English literature and criticism, Dr. Gouda pursued her education at both Ain Shams University and California State University, San Bernardino.

She has authored several academic works, including Lectures in English Poetry and Introduction to Modern Literary Criticism, among others. Dr. Gouda also played a significant role in translating The Arab Encyclopedia for Pioneers, a comprehensive project featuring poets, philosophers, historians, and literary figures, conducted under the auspices of UNESCO.

Recently, her poetry translations have been featured in a poetry anthology published by Alien Buddha Press in Arizona, USA. Her work has also appeared in numerous international literary magazines, further solidifying her contributions to the field of literary translation and criticism.