Live Encounters Poetry & Writing August 2025

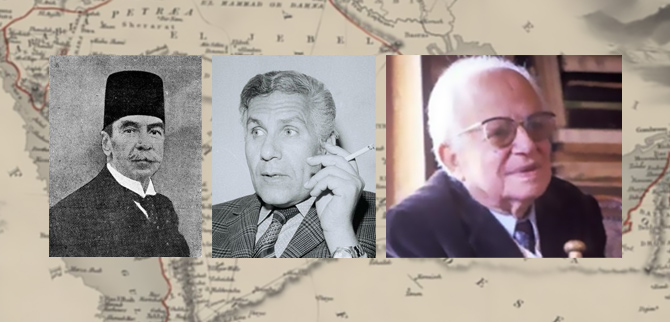

Taymour, Idris, Haqqi: Architects of the Arabic Short Story

guest editorial by Dr Salwa Gouda.

While the Arabic novel commands global attention, the short story has pulsed with a quieter, yet equally vital, energy within modern Arabic literature. Its emergence and evolution are inextricably linked to Egypt, where three towering figures – Mahmoud Taymour, Youssef Idris, and Yehia Haqqi – stand as foundational pillars, each shaping the form in distinct and enduring ways, navigating the transition from romanticism to piercing realism and laying the groundwork for profound social and psychological explorations.

Emerging during the twilight of the Nahda (Arab Renaissance), Mahmoud Taymour (1894-1973), often hailed as the father of the modern Arabic short story, witnessed profound societal shifts in early 20th-century Egypt – the waning Ottoman influence, British occupation, stirrings of nationalism, and jarring modernization. Beginning under the influence of romanticism and European models like Maupassant, Taymour crucially turned his gaze inward, moving beyond exoticism to focus intently on Egyptian society.

His stories delved into the lives of the Cairene middle and lower classes, peasants, and the marginalized, capturing tensions between tradition and modernity, rural roots and urban dislocation, bringing new psychological insight and commitment to authentic local reality. His prose, while formal, sought Egyptian nuances, exemplified in a character’s turmoil in “The Call of the Unknown”: “He felt his soul was a dark abyss, echoing with strange, frightening calls… calls that pulled him towards the unknown, towards a terrifying freedom he could neither comprehend nor resist.” This line captures the internal conflict between societal expectations and burgeoning individual desires, defining Taymour’s move towards psychological realism within the Egyptian context. Elsewhere, in “Aunt Nafisa,” he depicted tradition’s suffocating grip: “She lived as if wrapped in a cloak of ancient customs, each thread woven with the fear of God and the dread of people’s tongues. To step outside its folds was to step into an abyss,” illustrating the perilous cost of defying social norms.

If Taymour laid the foundation, Youssef Idris (1927-1991) detonated a literary explosion. A physician by training, Idris brought an unflinching, clinical eye to the raw underbelly of Egyptian life, rejecting the genteel realism of predecessors to plunge into the visceral world of the urban and rural poor with unprecedented intensity. His revolutionary genius lay in mastering colloquial Egyptian Arabic, infusing it not just into dialogue but the narrative voice itself, capturing the rhythm, humor, anger, and despair of the streets and villages. Idris depicted poverty, bureaucratic absurdity, sexual frustration, political disillusionment, and the sheer struggle for survival with brutal honesty, presenting flesh-and-blood characters often trapped and desperate yet pulsating with life and dark humor.

Collections like The Cheapest Nights reshaped expectations, proving the short story could be a blunt instrument of social critique and profound humanism from below, crystallized in his iconic line: “He felt that life was a cheap night, the cheapest of nights, where everything was sold: honour, conscience, manhood… and all for pennies.” This stark indictment, devoid of sentimentality and delivered in the raw language of the street, gave shocking power to the voiceless and dehumanized under systemic neglect.

His unsparing gaze captured the cyclical despair of the marginalized, as in “The Dregs of the City”: “The child’s bare feet slapped the mud, not running from something, but running toward nothing. That’s how we lived: chasing emptiness,” distilling the crushing futility of poverty. In stories like “The Chair Carrier,” he portrayed resilience amidst brutality: “They broke his fingers one by one. With each snap, he laughed louder. Pain was the only thing they couldn’t steal from him,” revealing defiance as a final refuge against oppression.

Yehia Haqqi (1905-1992) then brought a different, crucial dimension. A diplomat, intellectual, and master stylist deeply engaged with Arabic heritage and European modernism, Haqqi’s short stories leaned towards psychological depth, existential questioning, and consciously crafted, lyrical prose. While capable of sharp social observation (seen in his novel The Lamp of Umm Hashim), he explored alienation, identity, the burdens of the past, and the complexities of the human psyche with subtlety and nuance.

A meticulous craftsman concerned with structure, symbolism, and the musicality of Fus’ha (Modern Standard Arabic), his stories often featured introspective protagonists – intellectuals, artists, civil servants – grappling with internal conflicts and the meaning of existence within modern Egypt. He moved beyond pure social documentation to explore the inner landscapes shaped by those forces, as voiced by his protagonist in “The Postman”: “Who am I? A name on an envelope? A number in a file? A shadow passing through corridors? … I deliver letters, but who delivers me to myself?” This quintessential Haqqi lament reflects his preoccupation with identity, alienation within the bureaucratic state, and the search for authentic selfhood, delivered with introspective layering and melancholic wisdom.

In “The Saint’s Lamp,” he explored faith’s fragility in the modern world through potent metaphor: “Faith, he realized, was not a beacon on a hill, but a flickering wick in a broken lamp – barely lit, easily drowned by the world’s wind, yet stubborn,” capturing the delicate persistence of spirituality. His story “The Empty Bed” rendered profound loneliness tangible: “The emptiness beside him wasn’t space; it was time solidified. Years of silence pressed into the mattress like a fossil,” transforming absence into a palpable, haunting presence.

Together, these giants charted the modern Arabic short story’s course: Taymour transitioned it from romanticism towards authentic Egyptian social realism and psychological insight; Idris revolutionized it with raw, visceral power, colloquial language, and an unflinching focus on the marginalized, proving its potency for radical social critique; Haqqi elevated it with psychological depth, existential themes, modernist techniques, and mastery of literary Arabic, expanding its scope to explore the inner world shaped by outer realities.

They moved the genre from observing society to dissecting its soul. Taymour provided the map, Idris unleashed the torrent, and Haqqi reflected deeply on the floodwaters. Their innovations – the focus on the local and marginalized, embrace of colloquial rhythms, unflinching gaze at social ills, exploration of psychological complexity, and mastery of form – became the bedrock for generations of Arab writers. Their sparks ignited a flame that continues to illuminate the intricate, challenging realities of the Arab experience. The echoes of Taymour’s psychological abyss, Idris’s cheap nights, and Haqqi’s searching postman still resonate in the alleys and consciousness of Arabic fiction today.

Works Cited

- Badawi, M. M. *Modern Arabic Literature*, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Haqqi, Yehia. *The Saint’s Lamp and Other Stories*, 1944.

- Haqqi, Yehia. *The Empty Bed*, 1952.

- Idris, Youssef. *The Cheapest Nights*, 1954.

- Idris, Youssef. *The Dregs of the City*, 1958.

- Taymour, Mahmoud. *The Call of the Unknown*, 1939.

© Dr Salwa Gouda

Dr Salwa Gouda is an accomplished Egyptian literary translator, critic, and academic affiliated with the English Language and Literature Department at Ain Shams University. Holding a PhD in English literature and criticism, Dr. Gouda pursued her education at both Ain Shams University and California State University, San Bernardino.

She has authored several academic works, including Lectures in English Poetry and Introduction to Modern Literary Criticism, among others. Dr. Gouda also played a significant role in translating The Arab Encyclopedia for Pioneers, a comprehensive project featuring poets, philosophers, historians, and literary figures, conducted under the auspices of UNESCO. Recently, her poetry translations have been featured in a poetry anthology published by Alien Buddha Press in Arizona, USA. Her work has also appeared in numerous international literary magazines, further solidifying her contributions to the field of literary translation and criticism.

Thank you for this. Every day is a school day.

Thank you for this. This is the wonderful thing about LE. .. we are exposed to cultures and work.

Thank you, Terry, for your kind comment.