Live Encounters Arab Poetry & Writing April 2025

The Nile River: A Literary Lifeline Through Time,

guest editorial by Dr Salwa Gouda

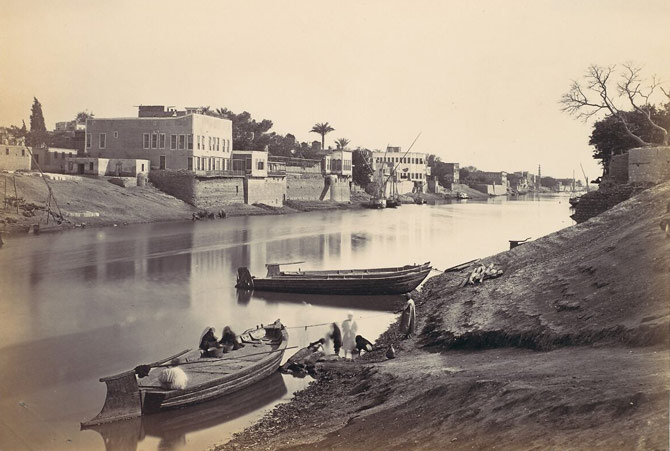

The Nile River, a meandering lifeline that carves through Africa’s deserts, has long transcended its role as a geographical marvel in Arabic literature. It stands as a symbol of life, a silent witness to history, and a mirror reflecting the soul of a civilization. From ancient hymns to contemporary novels, the Nile has carried the hopes, struggles, and dreams of countless generations. My own bond with the river runs deep, as I spent my early years in a family home perched on its banks. Back then, the Nile flowed with a tranquil grace, not only in its journey from south to north but also in the hearts and veins of the Egyptians who revere it. It has long been a cradle of civilization, a muse for poets, and a testament to nature’s enduring generosity. For millennia, its waters have nurtured cultures, inspired mythologies, and sustained ecosystems, creating a tapestry of human and natural grandeur that remains unmatched. This editorial delves into the river’s evolving portrayal across Arabic literary traditions, revealing how it has both shaped and been shaped by the cultural and political tides of the region.

In ancient Egyptian poetry, the Nile was often depicted as a divine gift, embodying the gods’ benevolence and the pharaohs’ might. The river was not merely a source of water but a sacred entity that sustained life and symbolized the cyclical nature of existence. In the Hymn to the Nile, attributed to Pharaoh Akhenaten, the river is celebrated as a source of fertility and abundance:

“Oh Nile, you rise in the heavens,

And your waters flow to the sea.

You bring forth the lotus flowers,

And the fish swim in your streams.”

This hymn captures the reverence ancient Egyptians held for the Nile, viewing it as a celestial force that connected the earthly realm to the divine. The river’s annual flooding, which deposited rich silt onto its banks, was seen as a manifestation of the gods’ favor, ensuring bountiful harvests and prosperity. The Nile was not just a physical entity but a spiritual one, deeply intertwined with the identity and survival of civilization.

The ancient Egyptians also personified the Nile as a god, Hapi, who was believed to control its waters. Hapi was often depicted as a figure with a potbelly, symbolizing abundance, and carrying offerings of food and water. This personification underscores the Nile’s centrality to Egyptian life, not just as a natural resource but as a divine presence that demanded reverence and gratitude.

Early Egyptian poets, influenced by Pharaonic reverence, wove the river into their verses as a sacred blessing. With the advent of Islam, the Nile’s symbolism deepened. The Abbasid poet Al-Mutanabbi, during his visit to Egypt in the 10th century, immortalized it as a manifestation of cosmic justice:

“Egypt—a land where all good flows,

Its Nile runs with the essence of justice.”

Also, the river’s literary presence flourished during the Islamic Golden Age. The Andalusian scholar Ibn Hazm, in his treatise The Dove’s Neckring, likened the Nile’s constancy to enduring love. Travel writers like Ibn Battuta marveled at its role in sustaining Cairo’s vibrant markets and intellectual hubs. In chivalric romances, such as The Adventures of Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan, the Nile became a stage for epic quests, symbolizing both abundance and danger. Its dual nature—nurturer and destroyer—resonated in folk tales, where floods could signify divine wrath or mercy. The Nile’s duality is particularly evident in Islamic folklore, where it is often portrayed as both a giver and taker of life. In one tale, a flood is sent as punishment for human arrogance, only to recede when the people repent. This narrative reflects the river’s unpredictable nature and its role as a moral arbiter in the collective imagination.

The 19th-century Arab Renaissance reimagined the Nile as a symbol of Egyptian identity and a national icon amid colonial rules. Ahmed Shawqi, the “Prince of Poets,” blended Pharaonic pride with anti-colonial sentiment:

“The virgin Nile, ransom of ancestral land,

Flows with our glories, as time itself marvels.”

Similarly, the poet Hafez Ibrahim portrayed the river as a silent ally in the struggle for independence. Prose writers like Rifāʿa al-Ṭahṭāwī linked the Nile’s fertility to Egypt’s intellectual revival, arguing that its waters nourished both fields and minds. This period marked a significant shift in the Nile’s literary portrayal. No longer just a divine or natural entity, the river became a political symbol, embodying the nation’s resistance to foreign domination and its aspirations for self-determination. The Nile was no longer just a source of life but a source of pride, a testament to Egypt’s enduring legacy and its capacity for renewal. Also, the Nile’s annual flooding, which brought nutrient-rich silt to the land, was seen as a symbol of renewal and rebirth. The poet Salah Abdel Sabour wrote:

“The Nile’s floodwaters bring us life,

And the land is reborn with the coming of the rain.

The river’s bounty is a gift from the gods,

And we are grateful for its life-giving waters.”

The 19th century also saw the rise of travel literature, where European and Arab writers alike marveled at the Nile’s grandeur. For European travelers, the river was often exoticized, a symbol of the “mysterious East.” For Arab writers, however, it was a reminder of their heritage and a call to reclaim their narrative from colonial distortions. Following the 1952 Egyptian Revolution, the Nile emerged as a voice for the marginalized. The vernacular poetry of Abd al-Rahman al-Abnudi infused the river with a proletarian spirit, narrating the hardships of farmers:

“The Nile laughs at dawn, shouts at oppression,

Waters palaces and waters the shacks.”

Further, Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz set his novel Miramar (1967) in an Alexandrian pension overlooking the Nile, using the river to reflect Egypt’s class divisions. The contrast between luxury hotels and fishermen’s huts along its banks underscored the nation’s social inequalities.

Moreover, Sudanese literature offers a unique perspective, capturing the Nile’s role in both unity and conflict. Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North (1966) juxtaposes the river’s serenity with postcolonial upheaval, symbolizing the tension between tradition and modernity. The Nile, in this context, becomes a metaphor for the nation’s struggle to reconcile its past with its present, to navigate the complexities of identity in a rapidly changing world. In the 21st century, the Nile’s literary identity grapples with environmental crises and globalization. Sudanese poet Al-Saddiq al-Raddi laments the river’s exploitation:

“They shackle your flow with cement and iron,

But who can shackle dreams or love?”

The Nile’s journey through modern Arabic literature reveals its remarkable adaptability. From a nationalist emblem during the renaissance to a voice for the oppressed in social realism, and now a rallying cry for ecological justice, the river remains a mirror to the region’s soul. As Sudanese American poet Emtithal Mahmoud writes:

“The Nile does not forget—

It carves its path through stone,

A testament to what persists.”

The river’s journey through Arabic literature is a testament to its enduring resonance. It has been a divine gift, a nationalist symbol, a witness to oppression, and a casualty of modernity. Yet, its essence remains unchanged: a symbol of resilience. As Mahmoud Darwish once wrote,

“The Nile flows within us… Not above,

It is the story, and the story remains.”

Darwish also wrote:

“The Nile is the artery of Egypt’s heart,

And its waters flow through our veins.

We are children of the Nile,

And its legacy is our heritage.”

In every era, the Nile has mirrored the Arab world’s triumphs and trials, proving that literature, like the river itself, is a force of perpetual renewal. Its waters, once sung by pharaohs, now inspire tweets and treaties, ensuring that the Nile’s story flows endlessly.

© Dr Salwa Gouda

Dr Salwa Gouda is an accomplished Egyptian literary translator, critic, and academic affiliated with the English Language and Literature Department at Ain Shams University. Holding a PhD in English literature and criticism, Dr. Gouda pursued her education at both Ain Shams University and California State University, San Bernardino. She has authored several academic works, including Lectures in English Poetry and Introduction to Modern Literary Criticism, among others.

Dr. Gouda also played a significant role in translating The Arab Encyclopedia for Pioneers, a comprehensive project featuring poets, philosophers, historians, and literary figures, conducted under the auspices of UNESCO. Recently, her poetry translations have been featured in a poetry anthology published by Alien Buddha Press in Arizona, USA. Her work has also appeared in numerous international literary magazines, further solidifying her contributions to the field of literary translation and criticism.