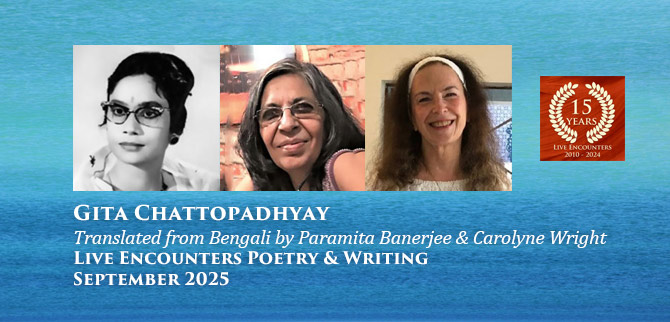

Live Encounters Poetry & Writing September 2025

Pujas and Politics: the Poetry of Gita Chattopadhyay,

poems translated from Bengali

by Paramita Banerjee and Carolyne Wright.

I’m Going to My Mother

Notes:

In a Field Already Harvested

of the Buddhist nun.

Notes:

What Is There to Be Sorry About?

Truce

Remove this metal armor, it hurts.

Let the breeze play on my bare body now,

undo the ancient brass lock from my heart.

Won’t your hand be a prisoner in mine?

Let the sky, the earth and the fourteen worlds know

the war is over now, Commander;

throw down your shield and sword, wash off

your scars and arrogance in water, remove the armor.

Remove the armor, the flowers will all be trampled;

their days won’t be numbered by raising victory pillars!

Time robs them of so much anyway,

at least let them be spared by your hand.

The day wears on, Commander; say how long twilight

can linger still on the battlefield with the close

of Raga Bhupali at sunset. Knowing shoreless

evening will descend, make peace, in a duet join hands.

Note:

Raga Bhupali (Rāga Bhūpāli) is a rāga to be played just at the hour of sunset.

Published in Bengali in Sapta Dibāniţi Kalkātā (Kolkata: Seven Days and Nights).

Kolkata: Kabi O Kabita, 1973. Copyright by Gita Chattopadhyay.

© Paramita Banerjee and Carolyne Wright

Gita Chattopadhyay was born in 1941 into a traditional zamindāri (large landholding) family in North Kolkata, in the family’s l75-year-old ancestral home, where she still lives with her widowed mother, a brother and two sisters, all unmarried. She was educated at the Baptist Mission School, then at Lady Brabourne College, University of Calcutta. After that she devoted herself to her writing—mainly of poetry and literary criticism—and to extensive reading in Bengali, Sanskrit, and English. Although she gave a few readings on All-India Radio, she lived essentially in seclusion, and remained an elusive and highly respected figure in contemporary Bengali letters until her passing in 2019. For all her privileged background and Dickensonian lifestyle, her work is among the most powerful and politically committed written in Bengali in her generation. Although she was wary of the commercialization of literature, her poems appeared in the magazines Kabi o Kabitā and Samved; and she published several volumes of poetry, essays, and verse drama, including a Collected Poems (কবিতা সংগ্রহ) from Aadam Publishers. In English translation by Carolyne Wright and Paramita Banerjee, her work has appeared in Artful Dodge, Calyx, Chicago Review, Crab Orchard Review, Field, International Quarterly, Poetry Review (U.K.), Primavera, and in the anthologies In Their Own Voice: The Penguin India Anthology of Contemporary Women’s Poetry, ed. Arlene R. K. Zide (Penguin India, 1993), Penguin New Writing in India, ed. Aditya Behl and David Nicholls (Penguin India, 1994), and Majestic Nights: Love Poems of Bengali Women (White Pine Press, 2008), ed. and trans. Carolyne Wright.

Paramita Banerjee was born in Kolkata in 1958, the daughter of two university professors. She received a B.A. with Honours in Philosophy at Presidency College, and an M.A. in Mental and Moral Philosophy from Calcutta University in 1981; and is currently completing her Ph.D. in Social Philosophy on a research fellowship from Jadavpur University. As a child, she wrote for several Bengali children’s magazines, and won prizes for her stories and poems. During her college years, she was involved in student politics, especially as an election organizer and observer in the frequently violent polling stations in rural West Bengal; at one point, she was beaten up by political party thugs and hospitalized for these endeavors. As an adult, she has been active in local political theatre groups and alternative bookstores, and has published articles on theatre and on women’s issues, as well as poetry, in a number of small literary magazines. She has written feature articles for the Calcutta English daily The Telegraph, published poems in Desh, and translated two novels of the late Samaresh Bose from Bengali into English for Penguin India. After a few years of editorial work at the publisher, Orient Longman, and teaching of Philosophy at Muralidhar Girl’s College in South Calcutta, she now directs Diksha, a non-governmental organization to provide social services and education to the children of prostitutes and other residents of the urban slums. She has three daughters, and lives with her family in Lake City, a suburb of Kolkata.

Carolyne Wright spent four years on Indo-U.S. Subcommission and Fulbright Senior Research fellowships in Kolkata and Dhaka, Bangladesh, collecting and translating the work of Bengali women poets and writers for a major anthology in progress. For these translations, she has received a Translation Fellowship from the Santa Fe Arts Institute, a Witter Bynner Foundation Grant, a National Endowment for the Arts Grant in Translation, a Fellowship from the Bunting Institute of Radcliffe College; and she has been a research associate at Harvard University (Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies), Wellesley College (Center for Research on Women), and Emory University (Asian Studies Program), where she also taught courses on South Asian Women’s Literature which were cross-listed with English and Women’s Studies. Volumes in Wright’s translation from Bengali published so far include Another Spring, Darkness: Selected Poems of Anuradha Mahapatra (Calyx Books), a renowned West Bengali poet about whom Adrienne Rich has written, “across culture and language we are encountering a great world poet.” Another published collection is The Game in Reverse: Poems of Taslima Nasrin (George Braziller), the dissident Bangladeshi writer living in exile with a price on her head. Most recently published is the anthology, Majestic Nights: Love Poems of Bengali Women (White Pine Press, 2008). Wright has published eleven award-winning books and chapbooks of her own poetry, and three other volumes of translation from Bengali and Spanish. Since moving back to her native Seattle in mid-2005, she has taught at the community literary center, Richard Hugo House; and was on the faculty for the Northwest Institute of Literary Arts / Whidbey Writers Workshop MFA Program until its closure in 2016