Download PDF Here

Live Encounters Poetry & Writing July 2023

Some Poems (Despite Their Serious Intent) Love to Play,

Are Inspired By The Ancestors – Guest editorial by Lynne Thompson.

When I served as Los Angeles’ 2021-22 Poet Laureate, many readers who had little experience reading poems often demurred when I encouraged them to listen to my podcast to acquaint themselves with the variety of contemporary poetic voices. They stated they didn’t—or feared they wouldn’t—understand it. It’s hard to argue with their reluctance as I’ve questioned for some time whether poetry is properly taught in schools. I’ve wondered if potential readers shouldn’t be taught poetry by working backward starting with poets writing today: from Douglas Kearney to Marwa Helal to Ada Límon to Robert Lynn Wood and only then back generationally to Sylvia Plath then on to Edgar Allen Poe then William Wordsworth and then William Shakespeare before sitting with Sappho, for example.

But poets and readers often come to the written word with pre-established stylistic preferences that can initially lead them to a more satisfactory reading of the genre. Some prefer a linear narrative approach. Some prefer an experimental style that leads to constant surprises, constant questions. There are those whose brains operate best within a visual context and the field of visual poetry is blooming in contemporary poetics. Finally—but hardly exclusively—some resort to traditional forms: sonnets, villanelles, pantoums. And none of these preferences are constant; rather those inclinations are like Shakespeare’s “inconstant moon, that monthly changes in her circled orb…”

Lately, my fondness for poets “at play” has grown exponentially. What can be found in their work is a nod to the various stylistic modes—and more—mentioned above while simultaneously declining to craft the work with relentless seriousness, no matter how serious the themes and their ultimate aims.

One of my favored style of poems at (serious) play are abcedarians. These poems rely on the seeming simplicity of the alphabet but can present as elegy or admonition or reverie. Often these poems bow to their audiences dressed in their glossary-gowns where “the first letter of each line or stanza follows sequentially through the alphabet” (Poetry Foundation). I took one of these lovely, though unsophisticated and possibly too eager, playmates out for a test drive with the following result:

Call It Havoc

as every step you take is clutch and coffin.

Believe me, baby-bent-on-starshine, you’re

crazy if you think you can get away by train.

Doubt is your best depend upon it,

especially when it was only a

few days ago when you cast bread—with

glee and hope—on a mirage.

Here’s a news flash: we’re all chumps who

ignore the fact we live in cities of the already-dead,

justice just a fairy tale,

kingdoms bellicose,

love-sick in these times of unloving….[1]

Ok, you get the idea. Luckily, I quickly learned that the approach to this exercise in poetic magic need not be so pedestrian. As far as one can get from pedestrian, for example, is the work of Harryette Mullen in her collection, Sleeping With the Dictionary” which includes one of my favorite poems “Any Lit.” An excerpt reads:

You are euphony beyond my myocardiogram

You are a unicorn beyond my Minotaur

You are a eureka beyond my maitai

You are a Yuletide beyond by minesweeper

You are a euphemism beyond my myna bird

You are a unit beyond my mileage

You are a Yugoslavia beyond my mind’s eye

You are a yoo-hoo beyond my minor key

You are a Euripides beyond my mime troupe

You are a Utah beyond my microcosm

You are a Uranus beyond my Miami

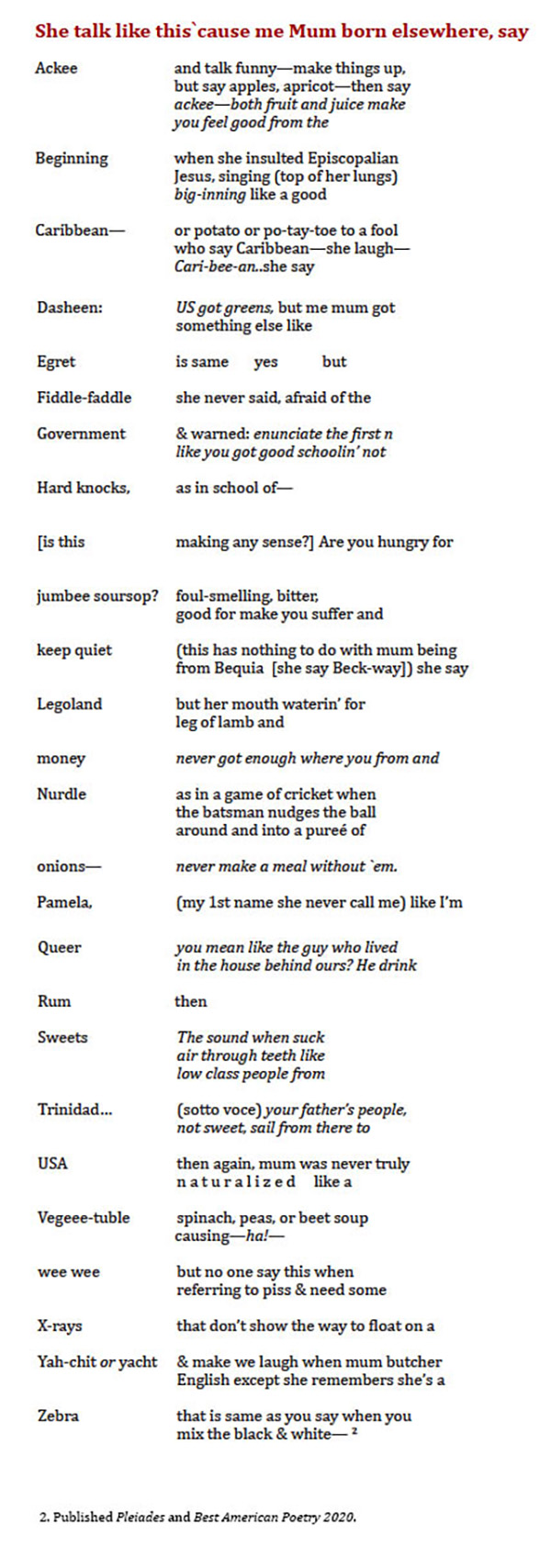

The poem’s obsession with “you” (and its variations “eu” and “yoo”) and “my” (and “mi” and “mai”) is heightened by an awareness that the alphabet is flexible and that sound is an element of poetry that plays an integral part in its design. It forms the basis of play in a poem that celebrates my mother’s Caribbean accent:

Having fun yet? If not, you may prefer something more serious; to rely, perhaps, on the creative directions the ancestors—either genealogical or literary—propose. Again, there’s a certain amount of “play” that these poems also employ. Cameron Awkward-Rich relies on his literary contemporaries and ancestors (Hieu Minh Nguyen, Franny Choi and Lucille Clifton, to name a few) in his poem “Cento Between the Ending and the End” to remind us:

Sometimes you don’t die

when you’re supposed to

now I have a choice

repair a world or build

a new one inside my body.

Cento is Latin for “patchwork” and, in poetry, is formed from lines of poems written by other poets as Awkward-Rich does in his poem above. In addition, the cento can rely on the work of just one poet as I did (relying on various first lines in Marge Piercy’s poems) and can address serious matters such as the children who live their first days as those who were once called foundlings:

Catch and Stick, Foundling

I was a girl-child, born as usual,

and every day whittles me.

Victim, not of accident, my vision is

catch-and-stick. There’s no difference

between being raped. When did I

first become aware? Who decided

what is useful to its beauty? The city

lies grey and sopping—a dead rat,

but living someplace else is wrong &

loving feels lonely amidst the violence.

© Lynne Thompson

Lynne Thompson was Los Angeles’ 2021-22 Poet Laureate and is a Poet Laureate Fellow of the Academy of American Poets. She is the author of three collections of poetry, most recently Fretwork, winner of the 2019 Marsh Hawk Poetry Prize, and of the forthcoming Blue on A Blue Palette that will be published by BOA Editions in Spring 2024. Her recent work can be found or is forthcoming in Best American Poetry, Kenyon Review, Massachusetts Review and the anthology In the Tempered Dark: Contemporary Poets Transcending Elegy. Thompson sits on the Boards of the Los Angeles Review of Books, Cave Canem and The Poetry Foundation.