DOWNLOAD PDF HERE

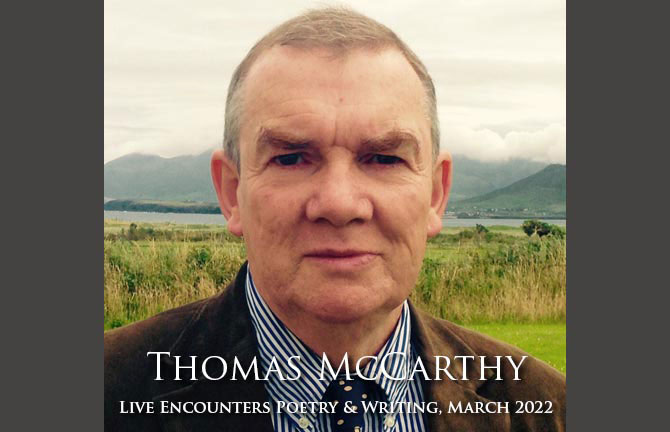

Thomas McCarthy was born at Cappoquin, Co. Waterford in 1954 and educated locally and at University College Cork. He was an Honorary Fellow of the International Writing programme, University of Iowa in 1978/79. He has published The First Convention (1978), The Sorrow Garden (1981), The Lost Province (1996), Merchant Prince (2005) and The Last Geraldine Officer (2009) as well as a number of other collections. He has also published two novels and a memoir. He has won the Patrick Kavanagh Award, the Alice Hunt Bartlett Prize and the O’Shaughnessy Prize for Poetry as well as the Ireland Funds Annual Literary Award. He worked for many years at Cork City Libraries, retiring in 2014 to write full time. He was International Professor of English at Macalester College, Minnesota, in 1994/95. He is a former Editor of Poetry Ireland Review and The Cork Review. He has also conducted poetry workshops at Listowel Writers’ Week, Molly Keane House, Arvon Foundation and Portlaoise Prison (Provisional IRA Wing). He is a member of Aosdana. His Pandemonium was published by Carcanet Press in 2016, and his collection, Prophecy, was published by Carcanet in April, 2019. Gallery Press, Ireland, has just published his journals, Poetry, Memory and the Party, in 2022. It is available here: https://gallerypress.com/product/poetry-memory-and-the-party/

Thomas McCarthy was born at Cappoquin, Co. Waterford in 1954 and educated locally and at University College Cork. He was an Honorary Fellow of the International Writing programme, University of Iowa in 1978/79. He has published The First Convention (1978), The Sorrow Garden (1981), The Lost Province (1996), Merchant Prince (2005) and The Last Geraldine Officer (2009) as well as a number of other collections. He has also published two novels and a memoir. He has won the Patrick Kavanagh Award, the Alice Hunt Bartlett Prize and the O’Shaughnessy Prize for Poetry as well as the Ireland Funds Annual Literary Award. He worked for many years at Cork City Libraries, retiring in 2014 to write full time. He was International Professor of English at Macalester College, Minnesota, in 1994/95. He is a former Editor of Poetry Ireland Review and The Cork Review. He has also conducted poetry workshops at Listowel Writers’ Week, Molly Keane House, Arvon Foundation and Portlaoise Prison (Provisional IRA Wing). He is a member of Aosdana. His Pandemonium was published by Carcanet Press in 2016, and his collection, Prophecy, was published by Carcanet in April, 2019. Gallery Press, Ireland, has just published his journals, Poetry, Memory and the Party, in 2022. It is available here: https://gallerypress.com/product/poetry-memory-and-the-party/

Greg Delanty’s No More Time, a book review

Greg Delanty’s No More Time, recently published by Louisiana State University Press in Baton Rouge, is not so much a celebration of the natural world as a lamentation for the extinction of entire species and the expression of craftily-controlled rage at the destruction brought about by the actions of humankind. It is a wondrous and beautiful poetry collection from a master formalist, a poet who seems to have been born with a metaphysical tongue and a God-given lyrical gift. I wish that every person who cares about environment and the wild could find a copy of this book. No doubt, like all good poetry books, it won’t be easy to find. But go find it.

Greg Delanty was born in Cork in 1958 but has been a resident in Vermont for many years where he works as a Professor of English at St. Michael’s College. Delanty, in all the years I’ve known of him and read his work, has never ceased to celebrate the abundance of life and to fight battles against the forces of mass destruction and earthly annihilation. The heft and seriousness of this new project in verse is immediately announced in its dedication page – the work is dedicated to, among others, his son and nieces, as well as to Greta Thunberg. It is a poet’s cry sent up to heaven on behalf of the future, a warning uttered by a modern Jeremiah, but composed formally by a gifted winner of the Patrick Kavanagh Award and a Guggenheim Fellow.

When he was a young poet in Ireland in the 1980s Delanty was a passionate supporter of Adi Roche’s CND, as well as a constant protester against cruise missiles and a fervent advocate of the wider peace movement. More recently he has become a hugely influential cultural voice in American environmentalist politics. So, he is no Johnny-come-lately to the environmental debate, his heart has been with the Green vision from the very beginning and his political activism is part of a deeply embedded character trait. In addressing his own father’s early death in ‘Interrogative’ (1992) he wrote: ‘even the flimsiest, most vulnerable creatures/ are equipped with devices to outwit death.’ The major thesis of this new collection from Louisiana State University Press is that death, empowered by the actions of humankind, has finally begun to outwit complex and innocent creatures.

When he was a young poet in Ireland in the 1980s Delanty was a passionate supporter of Adi Roche’s CND, as well as a constant protester against cruise missiles and a fervent advocate of the wider peace movement. More recently he has become a hugely influential cultural voice in American environmentalist politics. So, he is no Johnny-come-lately to the environmental debate, his heart has been with the Green vision from the very beginning and his political activism is part of a deeply embedded character trait. In addressing his own father’s early death in ‘Interrogative’ (1992) he wrote: ‘even the flimsiest, most vulnerable creatures/ are equipped with devices to outwit death.’ The major thesis of this new collection from Louisiana State University Press is that death, empowered by the actions of humankind, has finally begun to outwit complex and innocent creatures.

The collection’s overwhelming sequence here, its moral signature, is ‘A Field Guide to People,’ what the book’s blurb describes as ‘an alpha-bestiary of twenty-six sonnets.’ Each sonnet is an evocation of, or meditation upon, some natural thing, flora or fauna, that is either extinct or endangered. The present, stressed earth is seen as a purgatory or hell for living things, and poetry becomes the advocate or defender of all life under threat in our biosphere. Inserted between two groups of sonnets is ‘Breaking News,’ a sequence of wider cultural significance, an interruption of vast cultural, historical references. From Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and fall of the Roman Empire he has extracted the salutary tale of Emperor Heliogabalus, the Roman emperor of 204AD-222AD, who sought to confound the order of seasons and climates:

‘The emperor and his hobnobbing retinue

recline on the high dais. Everyone gazes

up at them from the floor. He winks to his chosen few,

mutters, “Watch this for a trap,” hollers, “Let’s

play. Bring on the grand finale….”

The grand finale was the shattering of a fake ceiling and the showering of crowds with pink roses. It was an impressive feat, but a coup against nature, an act of human madness that wouldn’t work out very well: for Heliogabalus or his distracted crowds. The emperor thought of himself as the invincible sun-king, maker of reality, but in the end he discovered that there was but one world, the one made by nature. Delanty’s human response to this litany of historical vanities is to reach for that great but humble weapon of the green movement, the bicycle:

‘You bike most everywhere these days,

wary of your part in the latest war, the slaughter

of innocents, the various wily ways

we’ve grown used to complicity’s tether.

The gas pump is an umbilical cord

Sucking the life out of Terra Mater.’

‘Dear Fellow Citizens,/ the answer to all our problems is around the bend’ he says in ‘State of the Union,’ a list-poem of poverty, racism, violence, water contamination, drug cartels and human trafficking:

‘No need for any distress.

Thank you, and God bless.’

In ‘Spiritus Mundi’ and ‘From The Vision of Mac Conglinne’ he addresses not hunger but gluttony: ‘A pool of colcannon/ under a thick butter/ lay between that and the ocean.’ The poet, like the wise Manchin of the old Cork myth of the Lough, hopes to coax insatiable demons from our indifferent bellies. If this project seems overly didactic, preachy, even, well tough luck. It is meant to be; it is meant not to be comforting. But the comfort, for readers of poetry, is in the craft; a precise, impressive poetry in poem after poem. In ‘One More Time’ the poet returns to a scene from his earlier life as a student in Ireland – when he, a champion swimmer, worked as a beach lifeguard during the Kerry summers of his College years. In this poem it is Mother Earth who requires resuscitation:

‘call the earth female, as of old.

She needs to be placed pronto

In the recovery position, gently hold

her chin up, bend the left arm at the elbow,

hand above the head, palm facing down

– Waving goodbye or hello?

Set the right arm straight and in line

with her side. Quickly tuck the left foot

up against the right knee, Watch for a sign

of breathing…………..’

The poem is a masterpiece, a combination of deep knowledge, pathos and leaping political metaphors. It is an example of Delanty’s deceptive aplomp; this memory of restoring life during a mid-summer emergency, all of it folded tightly into fourteen lines. His leaps of imagination, the risks he is prepared to take with language and metaphor, remind us constantly that though the book is an urgent appeal for environmental justice it is in the end, simply and completely, a work of art. Not to understand this would be an injustice to poetry everywhere.

The poem facing ‘Part 3’ is set as white type in a dark page. It is a memorial stone at the heart of the collection. ‘On a friend Visiting the Vietnam War Memorial’ outlines the litany of names placed on black marble in the great Vietnam memorial in Washington D.C. But instead of human names, the poet adds his own sacred litany:

‘…………………..imagine such a wall

listing plants and creatures since Noah

that we’ve undone, a roll call;

paradise parrot, Cape lion, great auk, moa,

Guam flying fox, dusky seaside sparrow,

St. Helena olive, passenger pigeon, quagga,

Laughing owl, Cry violet, Steller’s sea cow,

Caspian tiger, and more and more now and now.’

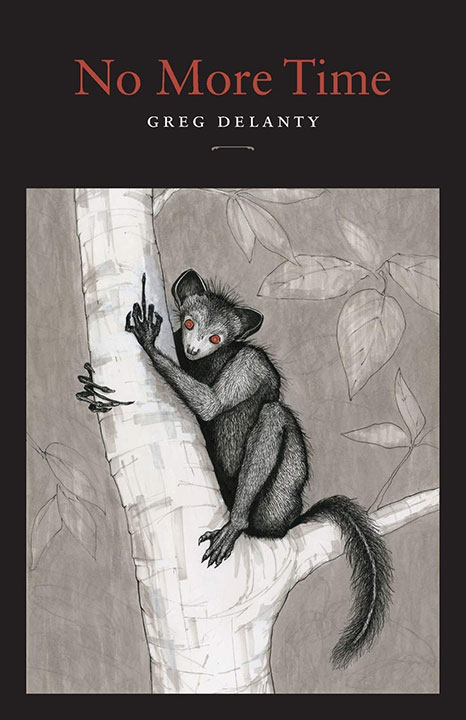

This is the method of the book, to name the endangered and the extinct. The superb cover drawing by Amber Geneva of the aye-aye, an endangered lemur whose disconcerting stare was said to harbinger certain death for the onlooker, is an inspired image. ‘Aye-aye, you continue to glare/ / back, your face a mirror, terror’s dead ringer,’ the poet writes in his sonnet to the mysterious, long-fingered creature.

The poet concedes that imagination can lead us into needless fear, like the fear of the aye-aye’s stare, but all of the important work assembled in No More Time by this very important Irish poet is a warning that our fears of environmental destruction are very real indeed. The book is an anthology of pleading creatures, given voice by a prophetic poet.

We have made our heavenly earth a hell for animals and plants. The rare achievement of Delanty here is that he has placed his art at the service of an important ethical epiphany, all the work charged with a single compelling message, but he has achieved this without any loss of aesthetic power or thrilling verse-craft. No More Time is a rare and important book, driving home to poetry – and to those who read poems – that ‘….we’ve made our mother ill./ Praise those who say there is hope still….’

Lyrics by Thomas McCarthy

I love also

The way birds in flight, bird motifs and fine drawings of birds

Draw you into their circle. It is as if there was something

In creatures of feathered flight, an improvisational air, a birdlike

Balancing act between the persistent patterns of wind and

The calculations of feathers, that responds to something

Not quite settled in you. I remember the owl at the hall door

Of old Parknasilla and how it spoke of you directly as if it knew

All the fiction you left hidden beneath stones from a time

When you were possessed with the migratory passions of

Youth. That owl had the dignity of George Bernard Shaw

And seemed to offer you a perch at the apex of a tall barn

In a fairytale. “Meet me later and we’ll catch some fat mice,”

The owl seemed to be saying. “Meet me later.” Today, it is

Tiny twittering song-birds hanging on for dear life in the

Catapult of fuschia branches in a force ten gale. They are,

You say, clinging in delicious fear like children on a fun-fair

Helter-skelter. They are born to this balancing act in a storm.

Women’s eight

A June sound like no other. A ventilator sound, or

The sound you come upon in the corner of a field

In late evening, the clunk-clunk of an electric

Fence, the pulse of things, of lungs and of danger.

Women pass me in a Senior Eight: no splash,

Not one splash from this Lee Rowing crew, but

The catch and slide in unison, the perfect

Motor of hours upon hours, the punch of bodies

As one. The power of them, the coach’s signature.

A waiter takes us

(In memory of Matthew Sweeney)

This is a restaurant that has a flame at its heart,

A place of singed linens

And charcoaled parts. Their menu is

The heaviest spirit we have ever opened

And the bodies within it

Are nothing more than a series of rumoured foods.

Matthew, nothing is heavier than promise,

And nothing more prophetic than egregious

Meat. Monkfish with its old vow of poverty

Is now a king bathing in veils of steam,

And nettle soup now as precious as Verdigris;

Stinging weeds are suddenly edible

And this square of Valentia slate as expensive

As a monogrammed poem. Your heart goes out to the world

Breathing of money, world of wishful and weak,

World of weary and of ennui. Meat comes to greet us

And to burn us back. Sweeney, we are pinned to the edge

Of this Donegal menu, the first

Part of conflagration already over. A waiter takes us

By the neck and shakes, making the wines to pass.

© Thomas McCarthy