Live Encounters Young Poets & Writers March 2021.

A native of Galway, Ireland, Geraldine Mills is a poet and fiction writer. She has published five collections of poetry, three of short stories and a children’s novel. She has won numerous awards for her fiction and poetry, including The Hennessy New Irish Writer Award, a Katherine Kavanagh Fellowship and has been awarded three Arts Council bursaries, the most recent being in 2020 to work on her second children’s novel. Her fiction and poetry are taught on Contemporary Irish Literature courses in the USA. She is a member of Poetry Ireland Writers in Schools’ Scheme. Her poetry collection, Bone Road in Word and Image (Arlen House, 2020) and some of her other titles are now available from:

https://www.kennys.ie/results/?q=Geraldine+Mills

https://www.bookdepository.com/search?searchTerm=Geraldine+Mills&search=Find+book

No one knows how language began, but from the dawning of our existence there has been the need to communicate. To put names to objects, ideas or actions. To make ourselves heard. To enunciate our needs. Children listened, learned from the language around them, the tongue of their people. And carried that on.

Some years ago, when my granddaughter was only two, we were coming back from a trip away. From her secure seat at the back of the car, she began to call out the names of the houses as their familiarity came into view. Her little petal mouth could barely form the words, but she made a valiant attempt at Mumu’s house, Tony’s house, Pheasant Farm, Nina’s house, Poppy’s House, Home. Already she knew the difference between house and home, the word for that safe place where she could go when the world was too big for her and she just wanted to be held close to her father, her mother. She sang the names again, her two-year old voice doing its level best to push out words from somewhere, words she didn’t know the day before. Rainbow, dreams, stars, were part of her song, as she demanded me to sing with her,

– my squeaky, granny voice out of tune– while she grabbed onto her new vowel sounds: O in rainbow, U in blue; I in fly.

Now five years later, she is writing those words down on windowpanes, mirrors, paper. Anywhere she finds a clear space, while her two and a half-year-old brother is at the same stage of finding the sounds that help define his language. Every day he successfully loops words together, being listened to in the art of communication. No matter the size of the word, – bat or brontosaurus– his little mind will search for the sounds and find a way of getting them out. Now when we chat with him across the miles, he has a conversation with us about the salamander he has seen on his way to the beach, the turtle his dad found abandoned in the wilderness, or his favourite dinosaur.

And words need children. Words need them to read the books whose pages they fill. They need them to bring the stories they create into their own existence as this new language seeps into them, so clean, so without criticism. They need them to continue to do this throughout their lives so that they can bring themselves to exciting worlds of the imagination.

In this time of Covid, children and adults alike are finding a world full of challenges. For children it is more important then ever that they read and write themselves out of this world crisis. To this end, Ireland held a day of reading on 25th February to encourage young and old alike to ‘Squeeze in a Read’ in order to encourage relaxation and wellbeing. Ireland Reads is a public libraries initiative, in partnership with publishers, booksellers, authors and others under the Government’s ‘Keep Well’ campaign. In this way we endorse the life-enhancing importance of books.

Normally, I would be visiting schools as part of the Poetry Ireland Writers in Schools’ Scheme. But that has been on hold for a year now. Yet teachers are still encouraging children to express themselves, to put shape on the world they are now living through as you will read in this edition, whether it is the love of horses, heroes or noses. Others explain their difficulty in lockdown.

One of the cultural outings I miss most about being unable to travel, is my annual visit to the treasury section of the National Museum of Ireland. This is one of the rooms dedicated to some of our most precious and holy artefacts. On display is the great treasure of the early Irish Church, the 8th Century Ardagh Chalice, with its spun silver, decorated with gold, amber and jewels. This was found by a boy at Ardagh in Co Limerick in 1868 when he was digging for potatoes. There is the Fadden More psalter, full of poems and psalms, written by monks about 900AD, found in a bog in 2006 when farmers cutting turf unearthed it and identified its calfskin leather, its papyrus inner page that showed their connection with the Coptic church in the east. There is the Tara Brooch, the Loughnashade Horn, the Cross of Cong. The museum has produced a trail guide for children which poses different questions challenging their observation of the intricacies of the craftmanship and myths attached. The last question asks the participant to choose their favourite object from the selection on display.

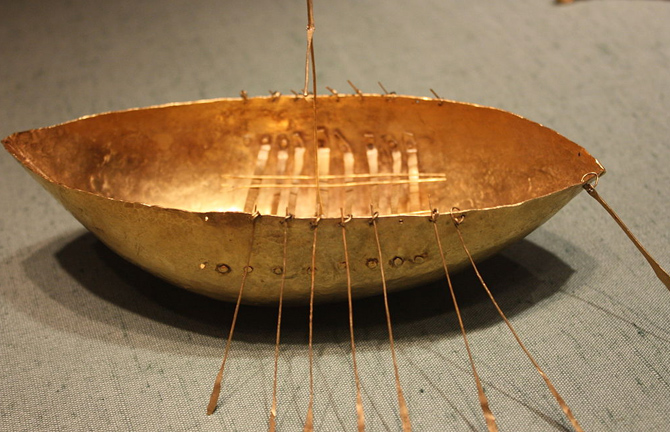

If I were filling it in, I would say without hesitation that the one that never fails to fill me with wonder is the Broighter Hoard. This was discovered in a field near Lough Foyle in February 1886 when two men were ploughing. Lough Foyle has always been connected to Manannán the sea god and this is quite possibly an offering to the god. The golden hoard consists of two chain necklaces, a small bowl or cauldron and a torc or gold collar. For me, the star of the piece is a miniature boat. It is an extraordinary piece of art that measures 18.4cm by 7.6cm and weighs a mere 85g. It has benches, rowlocks, two rows of nine perfectly shaped oars, a paddle rudder for steering and mast yard, all exquisitely crafted from gold. Looking at it I try to imagine the craftsman shaping the vessel, the world he came from, the need to create something beautiful.

Our young people are our lives best treasures. Like the Broighter Hoard, their creativity must be protected. Their jewels of words, their spun gold and silver of sentences, the intricacy of their artwork need to be safeguarded in the storehouse of books and journals, such as Live Encounters, where they will not be locked down, merely held in safe keeping for future readers.

© Geraldine Mills