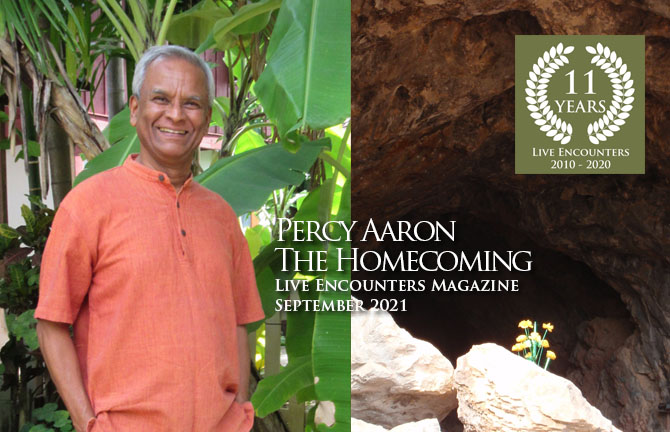

Live Encounters Magazine September 2021

Percy Aaron is an ESL teacher at Vientiane College in the Lao PDR and a freelance editor for a number of international organisations. He has had published a number of short stories, edited three books and was editor of Champa Holidays, the Lao Airlines in-flight magazine and Oh! – a Southeast Asia-centric travel and culture publication. As lead writer for the Lao Business Forum, he was also on the World Bank’s panel of editors. Before unleashing his ignorance on his students, he was an entrepreneur, a director with Omega and Swatch in their India operations and an architectural draughtsman. He has answers to most of the world’s problems and is the epitome of the ‘Argumentative Indian’. He can be contacted at percy.aaron@gmail.com

The Homecoming

Phet is crouched in the deepest interior of cave, eyes wide with fear. Resting his head against his father’s knee, he watches his five-year old twin, unafraid as always, playing catch-me-if-you can with some of the other village children. All around them people are screaming as they climb over those squatting near the entrance. Villagers who have found places are urging the stragglers to move faster. The cave is full but still they make place for the laggards. A dog, its tail tucked between its legs, is burrowing under the crouching bodies. Phet sees his grandmother at the mouth of the cave, hobbling inside on the arm of his aunt. The younger woman looks back anxiously; backwards, upwards. His mother pulls him and his father into another tunnel trying to create room where none is possible.

Then a blinding light and an ear-splitting explosion fills the cave with dust and debris. The next minute, his aunt, his grandmother and several others are just blood, bones and brains splattered over the rocks at the entrance. There is no time to grieve, or even scream. As the fires start, his mother grabs his hand. His father picks up another sibling, and they run, stepping into the crimson human pulp. All around them the cave is emptying as quickly as it filled up.

In the sky the warplane circles like a vulture observing carrion from above. As the villagers rush to the open rice fields, it turns around and dips down, slowing for a strafing run. Phet’s father stops and holds up his hand, they won’t make it, which right now is a good thing. In slow motion, they watch the plane’s machine guns stitching the shallow water of the rice fields, turning it from brown to red.

The next day the old man returns to work, breaking his back in his little rice field. Despite the deaths the previous day, grieving is an unaffordable luxury when so many mouths remain to be fed. But a few nights later, over a rusty mug filled with the locally brewed rice wine, the tears come for his mother, his sister and his son Thip, Phet’s twin.

***

Since that fateful day, life had moved on. Things were still difficult for most villagers. There was still the constant hunger but at least there was peace – some kind of peace. Now at least, those big birds in the sky no longer rained death and indiscriminate destruction.

True, most promises weren’t kept and there was no end to the sacrifices being demanded. True, some people were expected to sacrifice so much more than others. Villagers who were close to the important people visiting from the towns, always seemed to have more for doing so much less. The village chief spent less time in the fields and more time assembling them after a hard day’s work exhorting them to grow more food. The exhortations were always the same: work harder; give more; be patient; and always be vigilant, especially of the enemies in their midst. Phet’s father was really confused. Usually, the enemies were those villagers who cared and shared the most. Those who had fought hardest during the revolution, were now the ‘enemies in our midst’. The old man couldn’t understand. Most times there was never enough food in the village and yet when these people from the towns arrived, the food and drink were plentiful, at least at their table. On each visit, they took away more than half the rice and vegetables grown by the villagers. They were taking away the food to distribute to others who had nothing, they said but it was difficult to imagine any village having less food than this one.

About five years ago, Bounmy his friend, had asked these important people if he could accompany them as they distributed the food to distant villages. He went off with them, very excited at the opportunity to ride in a truck. But he didn’t return and later they told him that he was working for the Party in another part of the country. Selfish Bounmy, not even keeping in touch with his elderly mother. On another visit, Kham the hardest working of them all, had pointed out to these important visitors that they looked healthier and stronger than any of the scrawny villagers and maybe they should stop making speeches and help in the fields. A few mornings later, a couple of them came back and took him away to meet the big chief in the capital. Now more than three years later, he hadn’t returned to his struggling wife and three children. The village headman said that he had met another woman, much younger than his wife, and married her. So it was always with those complaining: leaving without even saying goodbye to family and friends.

As the years went by, life began to ease for some villagers. A few had relatives overseas, people who had left before or during the war. Now they sent back money or parcels. Then a message would come from the town and the lucky ones would journey to the post office there.

True they had to part with almost half of what they received but they never grudged this as it was going to help those villages that had even less. The village headman took a cut too, but that was because he gave the villager a lift into town on his dilapidated motorbike. Despite having to give away almost two-thirds of what was received, there was always enough for a few chickens to share with friends. Gradually, some homes started acquiring bicycles and transistors.

Occasionally a visitor would arrive from these faraway lands to see relatives, trace their roots, and even to marry a local girl. Then they would pay for the slaughter of a pig or two and the whole village would be invited to party.

Early this year a man arrived from America looking for a bride from this village. As always with these visitors, he wanted to impress the local people by being generous with his food and drink. Each night the villagers got together with this Lao-American, sharing his bourbon or offering their homemade brew. The prospective groom, twice divorced, was in his late fifties. While the bride-to-be was just nineteen. But she was beautiful and her impoverished family could do with the handsome dowry promised. One night, after the liquor had taken effect the reminiscing began. Family histories were related, roots traced and ghosts from the past resurrected. Stories from the war were told and retold and those who had died were remembered. But of so many, there was no trace. Most families had paid a heavy price.

Then one night the visitor mentioned a colleague from the same factory back in Minnesota who had lost his whole family in the caves that day the warplane had come. A stranger had grabbed the five-year old’s hand and run, not letting go. And she hadn’t let go even after crossing the border into Thailand, not through all the years in refugee camps, or later in wintry Minneapolis. Aunt Mai had adopted the little boy and cared for him all the years, until the cancer got her last year.

***

Down from the mountains they came and after two days of arduous travel, Phet and his family finally arrived in the capital, Vientiane. Now they were at Wattay International Airport in their finest tatters. Phet, his parents and his three sisters went up to the observation deck while their children went up and down in the lift, pressing numbers at random. After a while, somebody spotted a plane in the sky, and a shout went out. Phet looked into the sky and squinted as the giant silver bird descended. Then memories from thirty years ago came flashing back. He started to shake uncontrollably. His frail old father held his arm, not knowing whether it was excitement, or just his son’s recurring malaria. Steadying himself against the railing Phet pulled up his shirt and wiped his forehead. He choked back a scream and gripped his father’s arm tightly.

The panic subsided by the time the screaming monster taxied to a stop on the tarmac. Phet’s sisters were giggling nervously while their children, bored with the lift, were gaping at the big bird now spitting out tiny dolls of men and women. From the distance, he watched the passengers walking towards the terminal clutching bags or bundles in their hands. He stared hard at all the men but couldn’t identify his twin, despite all the photographs exchanged since contact had first been made.

They took the lift to the ground floor and Phet saw the crowds milling around the Arrivals gate. His mother pushed through the throng, her tiny frame slipping between the people in front of her. His sisters, already teary eyed, struggled not to burst with emotion in front of these slick city folk. His father, too scared to go to the toilet in case his son disappeared for another thirty years, had wet his trousers. He didn’t look well at all.

Phet didn’t know how he would react when he met his twin face-to-face. Even at five, his brother had been his hero, his universe.

Then Phet saw his mother being hugged by a muscular, handsome lookalike. From behind the crowds, he could hear her shouting, crying. His sisters were rushing towards their long-lost baby brother. As he helped his father forward, the old man stumbled. Phet struggled to hold him upright, then saw his father, eyes closed clutching his chest.

©Percy Aaron