Live Encounters Magazine August 2021

Dr Howard Richards (born June 10, 1938) is a philosopher of Social Science who has worked with the concepts of basic cultural structures and constitutive rules. He holds the title of Research Professor of Philosophy at Earlham College, a liberal arts college in Richmond, Indiana, USA, the Quaker School where he taught for thirty years. He officially retired from Earlham College, together with his wife Caroline Higgins in 2007, but retained the title of Research Professor of Philosophy. A member of the Yale class of 1960, he holds a PhD in Philosophy from the University of California, Santa Barbara, a Juris Doctor (J.D.) from the Stanford Law School, an Advanced Certificate in Education (ACE) from Oxford University (UK) and a PhD in Educational Planning, with a specialization in applied psychology and moral education from the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), University of Toronto, Canada. He has practiced law as a volunteer lawyer for Cesar Chavez’s National Farm Workers Association, and as a specialist in bankruptcy. He now teaches philosophy of science in the Doctoral Program in Management Sciences at the University of Santiago, Chile, and co-teaches “Critical Conversations on Ethics, Macroeconomics and Organizations” in the Executive MBA program of the Graduate School of Business of the University of Cape Town, South Africa. He is founder of the Peace and Global Studies Program and co-founder of the Business and Nonprofit Management Program at Earlham. Dr Richards is a Catholic, a member of Holy Trinity (Santisima Trinidad) parish in Limache, Chile, and a member of the third order of St. Francis, S.F.O

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Howard_Richards_(academic)

Overview

Overview

Methodological Remarks

1. Anger and Violence

2. The Economic Freedom Fighters

3. Mandela’s Choices

4. The National Development Plan

5. Economic Theory, Community Development and South Africa´s Community Work Programme

Consideration of the first five topics leads to an appreciation of the importance of the sixth.

1. Methodological Remarks

The brief discussion of constitutive rules in the introduction already hints at our sympathy with John Searle’s account of the construction of social reality, which he reads as the creation of institutional facts out of brute facts. Brute facts (like pieces of paper with certain markings on them) are assigned social status (like the status of money). That social status makes them institutional facts.[1] The rules that turn brute facts into institutional facts Searle calls constitutive rules.

A constitutive rule takes the form of ‘X counts as Y in context C’. To continue with Searle’s example: certain brute facts in the form of pieces of paper count as money in certain historical contexts. Another example (our adaptation of Searle, not pure Searle) is the legal rules that constitute property rights; here it is members of the species Homo sapiens who are the brute facts assigned a social status—that of ‘owner’. ‘Owner’ is an institutional fact.

The general acceptance of constitutive rules is the means by which cultural facts about meanings create material facts about social structure[2] and by which material relations are established among social positions. To revisit Sen’s example presented in the introduction, it is a constitutive rule that establishes who, at some given time and place, has a legal or customary right to eat and who does not. Transposing this idea from the Anglophone idiom of Searle and Porpora into the Francophone idiom of Michel Foucault, at certain historical moments material practices and regimes of truth converge to form dispositifs (devices) of power/knowledge.[3]

A key purpose of this book is to contribute to rebuilding not only economic theory but also the basic social structure that (mainstream) economic theories presuppose. However, this effort begs for sympathy. The words available to us as building materials denote essentially contested concepts. They are words with long histories marked by socially violent and academically convoluted confrontations. We therefore find ourselves in a distressing situation not unlike that of seasick passengers on Neurath’s boat.[4]

Otto Neurath likened scientific knowledge to a boat that must be repaired while at sea. The sailors must reconstruct the boat they are sailing on, so they can replace only one plank at a time. If they removed and replaced too many planks at once, the boat would sink. Similarly, we are constrained to work with mainstream thinking and the basic social structure as they are, even when we believe they are mistaken not just at a few points but ab initio (from the beginning).

Our situation, however, is even worse than that of Neurath’s sailors because, much more than the history of physics that Neurath mainly had in mind as his boat, the history of economics is a history of the construction of social realities. We claim that economic theory did not arise just to understand its object of study, i.e., modern economic society; it arose as part of the social construction of its object of study. Adam Smith was not just a student of market exchange; he was an advocate and an architect of a society under construction whose most powerful institution would become market exchange organized by the rule of law.

Our situation, however, is even worse than that of Neurath’s sailors because, much more than the history of physics that Neurath mainly had in mind as his boat, the history of economics is a history of the construction of social realities. We claim that economic theory did not arise just to understand its object of study, i.e., modern economic society; it arose as part of the social construction of its object of study. Adam Smith was not just a student of market exchange; he was an advocate and an architect of a society under construction whose most powerful institution would become market exchange organized by the rule of law.

Economics did not begin with Smith’s political economy or as a science at all. Before it was a science, it was a moral and political movement in favour of what was called natural liberty.[5] Preexisting social structures in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries established what Foucault would call the historical conditions of the possibility of economics. These conditions were established only in Europe; economics as we know it became possible in the rest of the world only when its European conquerors brought European law and customs with them.[6] Among the preexisting discourses that facilitated the emergence of the discourse on political economy in Western Europe were those of Roman law, the similar common law of England, eighteenth-century notions of natural rights and social contracts, Protestant theologies, several schools of ethics, and Newtonian mechanics.

Our plight now, in the twenty-first century, is that of passengers on Neurath’s boat who wish they had some influence over the direction the boat is going but have good reason to doubt that they do. Today, an account of economic theory should—so we claim—offer ideas about where society is going and why, and about how to change economic theory’s object of study: the basic social structure. It should give people hope that they can contribute to transforming economic society. It should propose a strategy for changing the course of history.

This book does indeed propose such a strategy, and it intends to encourage readers to believe they can make a difference. The strategy, which we call unbounded organization and ethical realism, hits the ground running by building on community development methods that already exist and are already achieving some success.

The discursive approach of this book starts from the premise that one will not get far in changing the linguistic side of discourse without changing its practical side. For this reason, this book includes many pages filled with brute facts. Otherwise put, if, in terms of Searle’s story about how to construct social reality, the brute facts are where the institutional facts come from, and if we want to change the institutional fact that humanity is currently condemned to live under one or another regime organized to facilitate accumulation to the detriment of nature, then we would be wise to ground our search for change strategies at the brute-fact level.

Some might challenge our approach by claiming that there are no brute facts. For instance, while John Searle proposes a plausible vocabulary and viewpoint in which concepts like brute fact and basic fact are given reasonably clear, nuanced meanings, Martin Heidegger proposes an equally plausible vocabulary[7] expressing a quite different viewpoint. Most people would agree that every so-called brute fact is actually a description by some speaker speaking some language. It does not necessarily retain the same brute status when it figures as a fact in some other speech. Martin Heidegger goes further: To see something is already to interpret it;[8] that is, we cannot see without Auslegung—without interpretation, without reading. Even before we open our mouths to describe a fact and thus sully the fact’s pristine bruteness with the cultural baggage of our language and our extempore choice of words, our eyes have already betrayed us.

O ur defence, our appeal to the mercy of the court, as it were, is that we will do our best to ground our word choices in physical realities (ecology) and in the realities of people’s lives (what they experience). To back up our defence we again call upon the author of Reclaiming Reality,[9] Roy Bhaskar, as a witness to make one key point that he qualifies at length elsewhere in his extensive writings. He testifies that, although it is true that every fact is a fact only under some description and only in the light of some way of seeing, it is also true that science can detect underlying causal powers that produce observed phenomena. So it is okay to repose some faith in a naturalist worldview (in an emergent-powers materialism neither wholly like nor wholly unlike Searle’s naturalism) and at the same time agree with Heidegger that all seeing is seeing as. Roy Bhaskar’s early work (known as ‘first wave critical realism’) was nothing if not a reconciliation of science and hermeneutics; we intend to stand barefoot on his shoulders and let our ankles be tickled by his long hair.

ur defence, our appeal to the mercy of the court, as it were, is that we will do our best to ground our word choices in physical realities (ecology) and in the realities of people’s lives (what they experience). To back up our defence we again call upon the author of Reclaiming Reality,[9] Roy Bhaskar, as a witness to make one key point that he qualifies at length elsewhere in his extensive writings. He testifies that, although it is true that every fact is a fact only under some description and only in the light of some way of seeing, it is also true that science can detect underlying causal powers that produce observed phenomena. So it is okay to repose some faith in a naturalist worldview (in an emergent-powers materialism neither wholly like nor wholly unlike Searle’s naturalism) and at the same time agree with Heidegger that all seeing is seeing as. Roy Bhaskar’s early work (known as ‘first wave critical realism’) was nothing if not a reconciliation of science and hermeneutics; we intend to stand barefoot on his shoulders and let our ankles be tickled by his long hair.

Having set out our methodology, we offer next a plausible description of facts about contemporary South Africa. While these facts may not be wholly brute, they are at least more brute and less institutional than—to cite an economic theory discussed later—Dani Rodrik’s theory of economic growth.

2. Anger and Violence

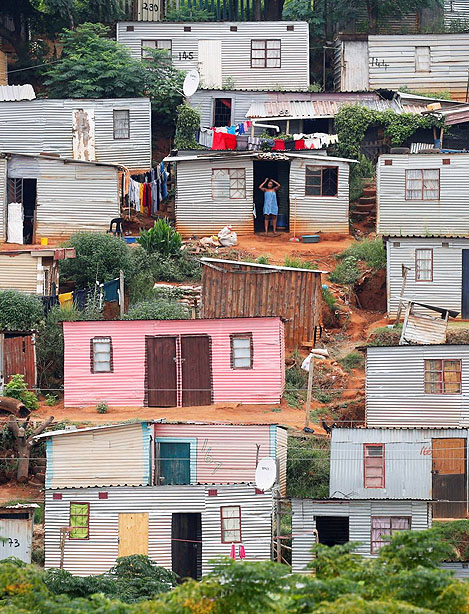

A wave of violence swept across South Africa’s poor townships starting in May of 2008. In some places it was preceded by a history of protests dating back as far as 1996, just two years after democracy was established in the country. It was followed by even more protests, many of them violent, in the succeeding years. We focus on 2008 and 2009 because we have access to careful case studies of those years’ violence at eight locations.[10]

Various incidents triggered the violence. Protests led to mass meetings and marches. Then came the burning of private and public buildings, and work stay-aways and deaths. Once the protests began, the police became a factor, either because of their absence or because their excessive violence led to running battles between youth and police. In most cases, there were attacks on foreigners and foreign-owned shops and dwellings, and in one case study (of Slovoview), the researchers found xenophobic violence to be the primary violence.[11]

A common trigger for the violence was real or alleged corruption; for example, in the town of Voortrekker in the province of Mpumulanga, the trigger was the disappearance of 150 thousand rands. Whatever the underlying structural causes may have been, the proximate cause of that violence was that money intended as prizes for winning athletes in a competition had disappeared. Somebody had stolen it.

In each case of violence studied, there was some form of broken trust or broken promise. For example, a protest organizer in Voortrekker asserted: ‘That the houses were burnt down was the mistake of the premier. He promised to come but did not.’[12] Sometimes the violence was triggered by a faction in local politics mobilizing popular discontent to serve its own interests. A protestor at Kungcatsha described the discontent this way: ‘People of this township are very patient, but this time they are very angry. They are sick and tired of waiting.’[13] Another described partisan and even self-serving mobilization: ‘Some of the leaders were angry that they were no longer getting tenders, and then they decided to mobilize the community against the municipality.’[14]

Over and above the particular sparks that ignited particular conflagrations, three recurrent fact patterns stand out. The first pattern underlies the partisan mobilization of discontent and is well summarized by Karl von Holdt, author of one of the case study reports: ‘Using the appropriation of state activities as a basis for accumulation, a thuggish local elite is able to rise through a combination of criminal, extra-legal and quasi-state activities.’[15] The protests frequently did not target the national government or the ruling African National Congress. Rather, they targeted the misdeeds of local authorities and then looked to higher authority to correct them.

The second pattern is the continuity of the ideas and repertory of the protest activities with those of the decades-long anti-apartheid struggle before 1994. A protestor in Azania said, ‘The Freedom Charter says people shall govern, but now we are not governing, we are being governed.’[16] During the struggle against apartheid and again in 2008–2009, violence was preceded by peaceful protest in the form of mass meetings, marches, petitions and strikes. During both periods of protest, the burning of a public building—a library, a clinic, a community centre—was a symbolic disruption of oppressive authority. The report says, ‘It is a symbolism that is well understood, both by community and by authorities, since it was central to the struggle against apartheid authority.’[17] Burning down the homes of local authorities perceived as corrupt in 2008–2009 was similar to the burning out of collaborators practiced in the 1980s. The protestors of the later era burned tyres and barricaded streets, as their predecessors had done. They engaged in toyi toyi, marching aggressively while singing struggle songs. Video footage of protestors at Voortrekker shows them chanting Tambo, kumoshekile; bayasithengisa—‘Tambo, things are bad; we are being sold out’—referring to Oliver Tambo, who headed the African National Congress during the freedom struggle.

The third and most fundamental pattern is the contrast between the prosperity promised to the masses during the struggle against apartheid and their present reality of grinding poverty under democracy. Jacob Dlamini, in his report on violence at Voortrekker, provides some detail: ‘In Mpumalanga, as in the rest of South Africa, despite the ANC commitments to eliminating poverty and the expectations of the majority of black people, poverty and inequality have increased dramatically since 1994. For example, South Africa’s Gini coefficient [a measure of inequality] moved ahead of Brazil’s to become the world’s worst among major countries: from 0.66 in 1993 to 0.70 in 2008. The income of the average African person fell as a percentage of the average white’s from 13.5 percent (1995) to 13 percent (2008) (Development Policy Research Unit, 2009).’[18]

Young protestors in Azania Township responded angrily to the suggestion that, in protesting, they were being manipulated by the local elite. One said: ‘It is an insult to my intelligence for people to think we are marching because someone has bought us liquor. We are not mindless. People, especially you who are educated, think we are marching because we bored. We are dealing with real issues here. Like today we don’t have electricity. We have not had water for the whole week.’[19]

The violence of 2008 has recurred at different moments and places in the years since then. At times it takes the form of service-delivery protest, or xenophobic violence, or, as a daily painful reality, violence against women and children. Violence is an ongoing social reality for the vast majority of South Africa’s people.

3. The Economic Freedom Fighters

We write here of a particular political party now (in 2019) active in South Africa. In the interim between when we write this and when someone reads this, this party as a specific movement may have waxed, waned, or disappeared. But political movements that articulate and mobilize popular discontent will not disappear. They will recur as long as there is popular discontent and as long as there is politics.[20]

On July 26, 2013, on the sixtieth anniversary of Fidel Castro’s unsuccessful storming of the Moncada Barracks in Havana, a radical movement rolled out its founding manifesto in Soweto, South Africa.[21] They called themselves Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), and they called their leader commander-in-chief. They cast themselves as the finishers of the unfinished revolution that had won democracy for South Africa. In their manifesto they state that political power without economic emancipation is meaningless:

On July 26, 2013, on the sixtieth anniversary of Fidel Castro’s unsuccessful storming of the Moncada Barracks in Havana, a radical movement rolled out its founding manifesto in Soweto, South Africa.[21] They called themselves Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), and they called their leader commander-in-chief. They cast themselves as the finishers of the unfinished revolution that had won democracy for South Africa. In their manifesto they state that political power without economic emancipation is meaningless:

Concerning real economic transformation, the post-1994 democratic state has not achieved anything substantial owing to the fact that the economic-policy direction taken in the democratic-dawn years was not about fundamental transformation, but empowerment/enrichment meant to empower what could inherently be a few black aspirant capitalists, without the real transfer of wealth to the people as a whole.[22]

The Freedom Charter of 1955 had inspired much of the resistance to apartheid before the African National Congress (ANC) came to power in 1994. It continues to play an important role in South African politics. The Manifesto of the EFF reads the Freedom Charter radically. The Charter says that South Africa belongs to all who live in it. In the EFF Manifesto, that principle is read to imply public ownership of natural resources and key industries,[23] as well as nationalization of mines, banks and monopolies. It is also read to mean that the state should assure economic opportunities to all.

The Charter also says that while the state should be in control of the commanding heights of the economy, ‘people shall have equal rights to trade where they choose, to manufacture and to enter all trades, crafts, and professions’. Therefore, there will never be nationalization and state control of every sector of South Africa’s economy.[24] However, says the Charter, ‘there will be cooperatives and other kinds of common and collective ownership’.[25]

The EFF Manifesto goes on: ‘The struggle for economic freedom is not a struggle against white people, but a struggle for the emancipation of the working class and for equal benefit of those who are not benefiting from the current economic realities.’[26] It declares that the EFF will be present at the barricades. It will be involved in mass movements and community protests.[27] From this it appears to be reasonable to anticipate that, in the future, successive waves of protest triggered by local issues will be joined and supported by militants of one or more national organizations with a definite ideology.

In its Manifesto the EFF self-identifies as leftist, anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist. It purports to draw inspiration from Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Frantz Fanon and all those who over the centuries have struggled for the economic liberation of humanity. In 1992, Francis Fukuyama looked around the world and concluded that history was over;[28] from then on and into the indefinite future, all leftist ideologies would remain in the dustbin—defeated, disproven and discredited. The EFF Manifesto of 2013 says ‘not anymore’. Not in South Africa.

However, the admiration of the EFF for nineteenth- and twentieth-century leftist revolutionaries appears to be more a matter of honouring the lives of heroes than one of advocating an economic model like that of the former Soviet Union. (When it comes to naming models, according to the EFF, South Africa can learn from the countries on an honour roll that includes Brazil, India, China, Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan and Finland.) Much of the Manifesto is not so much about the choice of an economic model as it is about basic morality (which critics of the EFF are quick to charge its leadership with violating). It denounces the juicy perks of public officials, cronyism, sexism, silencing the truth for fear of losing your job, putting profit before people and self-serving venality.

It declares seven cardinal pillars of a strategic mission for economic freedom in our lifetime.[29] The seven cardinal pillars are (slightly simplified) as follows:

1. Expropriation of South Africa’s land, without compensation, for redistribution in use. (Redistribution in use is later explained as granting permits to use land for up to twenty-five years for stated uses, presumably mainly as farmland.)

2. Nationalization of mines, banks and other strategic sectors of the economy without compensation.

3. Building state and government capacity, which will lead to the abolition of tenders.

4. Free quality education, health care, houses and sanitation.

5. Massive protected industrial development, leading to jobs and adequate minimum wages for all.

6. Massive development of the African economy on the entire continent.

7. Open, accountable and corruption-free government.[30]

While the EFF’s campaigns against corruption and its admiration for Asian developmental states are not especially radical, its first two cardinal pillars are undoubtedly radical. Not even five years after the party’s launch, however, the call for the expropriation of land without compensation had won such a degree of support that the ruling ANC adopted the same position.

Were these pillars to become facts on the ground, they would lead to what Lewis Coser calls ‘absolute conflict’.[31] In an absolute conflict, the parties do not acknowledge a common frame of reference for rationally negotiating a compromise or a mutually agreed-upon settlement. In the terminology of the ancient dialogues featuring Socrates and composed by Plato, there is no presiding logos (reason or plan) for making the outcome of the argument independent of the will of the arguers. Nothing enables the arguers to convince each other with reasons. Let us look at the two views of this issue.

In the first view, which is the EFF’s discourse, the dispossessed have been cheated and have a right to take back what is theirs. The liberation movement had promised that a free South Africa would belong to all its citizens. Liberation came, but that promise was not kept. Therefore, the anger of the masses, articulated and mobilized by the EFF, is righteous.

Quite apart from the unkept promise made in the Charter, a number of arguments can be made in support of sharing property. One is that communal property is a desirable part of the cultural heritage of South Africa; it was suppressed through force of arms by European conquerors and should in some form be restored. According to that heritage, the land is sacred to the ancestors, while the living are stewards of it and use it (prefiguring the EFF’s proposal to organize use without ownership) not only for themselves but to improve it for those yet unborn.[32] Africans did not know or practice the Roman law concept of dominium, imposed on them by colonialism and now enshrined in the rules of the World Trade Organization that are obligatory throughout the global economy.[33] This indeed is one of the constitutive rules of modernity spoken of earlier. The Africans did not accept modernization (read: marketization and immersion in the cash economy) willingly but had to be coerced—for example, by being forced to pay a tax in money, which in turn forced them to work in the mines or on farms to earn the money.[34]

Quite apart from the unkept promise made in the Charter, a number of arguments can be made in support of sharing property. One is that communal property is a desirable part of the cultural heritage of South Africa; it was suppressed through force of arms by European conquerors and should in some form be restored. According to that heritage, the land is sacred to the ancestors, while the living are stewards of it and use it (prefiguring the EFF’s proposal to organize use without ownership) not only for themselves but to improve it for those yet unborn.[32] Africans did not know or practice the Roman law concept of dominium, imposed on them by colonialism and now enshrined in the rules of the World Trade Organization that are obligatory throughout the global economy.[33] This indeed is one of the constitutive rules of modernity spoken of earlier. The Africans did not accept modernization (read: marketization and immersion in the cash economy) willingly but had to be coerced—for example, by being forced to pay a tax in money, which in turn forced them to work in the mines or on farms to earn the money.[34]

Throughout the world precapitalist and non–Roman law traditions express, in one way or another, the idea that the resources of the earth should be shared and used for the good of all.[35] Pope Francis I underscored this tradition when he wrote in 2013 of ‘creating a new mentality that thinks in terms of community, of the priority of the life of all over the appropriation of property by some’. He continued: ‘Solidarity is a spontaneous reaction of those who recognize the social function of property and universal purpose of property as realities prior to private property. The private possession of property is justified to the extent that it serves to take care of it and to use it to better serve the common good. Therefore, solidarity should be lived as a decision to return to the poor what belongs to them.’[36]

There is, then, a convincing logic underpinning the EFF (and later the ANC) position about land expropriation. However, if we apply here Heidegger’s insight that all seeing is seeing as, all seeing is interpretation,[37] then expropriating the commanding heights of the economy and using them to serve the good of all can not only be seen as justice for reasons such as those sketched above; it can also be seen as tyranny. In the first place, the social rule of private property is so ingrained in modernity that any diversion from it appears anarchic and destructive to the economy; indeed the South African Banking Council issued a strongly worded condemnation of appropriation without compensation, noting that the entire banking system was underpinned by loans against land.

In the second view, in opposition to the EFF’s stance, one can imagine the anger of men and women faced with expropriation of land they ‘own’ without compensation by an EFF-led government. Regardless of what happened during the past few hundred years, in their own memory and the fairly recent past, they bought their land with hard-earned money. They put their own sweat, blood and tears into farming it. These people, farmers and city dwellers alike, are not likely to see EFF government officials as saints who selflessly administer the land for the benefit of all. They are more likely to see them as twenty-first-century versions of the monarchs of old who stole whatever they wanted from their subjects until, thank God, modern republican constitutions were instituted to protect the people against having their property seized by their rulers. They are likely to see them as twenty-first-century versions of twentieth-century dictators who stripped citizens of all their rights. They will send a call around the world to show how the basic rules of the game are being flouted in South Africa. Solemn promises to protect property rights were part of the democratic transition and then became part of the Constitution. International law will support them, not least because South Africa has signed and ratified international treaties guaranteeing human rights that include property rights.

This brief analysis suggests that the radical pillars of the EFF Manifesto would indeed lead to absolute conflict. Even if the EFF as an organization proves ephemeral, similar thinking proposed by another organization would lead to absolute conflict, with no apparent common moral framework that could be a basis for negotiation, compromise or cooperation.

The facts are telling us that economic theory bears on questions more serious than the allocation of scarce resources among competing uses. It bears on meeting basic needs without which life cannot go on (what heterodox economists sometimes call ‘provisioning’). It bears on creating social peace and on avoiding civil war.

In this book, we advocate for unbounded organization as a successor to conventional economic thinking and a contribution to management science. In the course of this text we will explore fully what we mean by ‘unbounded organization’. For the moment, we mention two supporting lines of thought that count, among their benefits, the defusing of absolute conflict over property rights. The flexibility these lines of thought offer is to be contrasted with the rigidity of the juridical framework that has been decisive for the social construction of both economic society and the science that studies it. They suggest that there are superior alternatives to the conventional economic response given by South Africa’s National Development Plan (NDP), which promises, though not credibly, economic growth as a path to defusing conflict by enriching all parties. Our hope is that these two lines of thought will help South Africa to step back from the brink of absolute conflict.

The first such line of thought is ethical realism. For a realist ethical philosophy, there are no absolute rights; therefore there can be no absolute moral conflict, as when one party claims to have an absolute right incompatible with an absolute right claimed by the other party. The nonexistence of absolute rights entails that anyone who claims to have such rights is mistaken.

Rights talk is often recommended for good, practical reasons, one such good reason being the observed empirical fact that the security of property rights keeps the wheels of industry turning and the ploughs of agriculture churning.[38] However, the very fact that rights talk is recommended for good practical reasons implies that there can be good practical reasons for backing off from rights talk when it leads to absolute conflict. By the same token, there can also be good reasons for modifying property rights. Once we start having rational conversations about the social functions of property, we can take into account empirical evidence supporting the idea that property rights usually work better when they are more widely distributed, when more of them are common, and when more of them are public.[39] For a realist, a pragmatic compromise is not a second-best solution that falls short of the ideal; pragmatic compromise is the ideal.

The second line of thought consists of whatever improves social theory and transformative practice. As things now stand, the poor people of South Africa are urged to be patient because help is on its way in the form of social and economic development. They are told that their eventual prosperity will be delayed or will not come at all if they frighten away investors. They are admonished not to listen to populists. Behind such pleas to the poor lies a faith, widespread among governing elites, in the teachings of mainstream liberal economics. But if it is the case—and we will argue that it is the case—that mainstream liberal economics does not work for the poor, then the faith elites have placed in it is erroneous, and the grounds for asking the poor to be patient lack credibility.

The second line of thought consists of whatever improves social theory and transformative practice. As things now stand, the poor people of South Africa are urged to be patient because help is on its way in the form of social and economic development. They are told that their eventual prosperity will be delayed or will not come at all if they frighten away investors. They are admonished not to listen to populists. Behind such pleas to the poor lies a faith, widespread among governing elites, in the teachings of mainstream liberal economics. But if it is the case—and we will argue that it is the case—that mainstream liberal economics does not work for the poor, then the faith elites have placed in it is erroneous, and the grounds for asking the poor to be patient lack credibility.

Stepping back from the brink of absolute conflict calls for a more believable story. We offer our unbounded approach as one such story. We believe it contributes to building better social theory and more effective practices that will, in turn, contribute to defusing violence. The spectre of absolute conflict will fade away to the extent that better science leads to better practical results that demonstrate sincerity and meet needs.

Related to the topic of how the absolute conflict inherent in talk of absolute rights might be defused are a pair of questions. The first is whether government control of the commanding heights of land, banking and industry would or could lead to the results desired. The second is whether the absence of government control of the commanding heights of the economy would or could lead to the results desired. One of the aims of this book is, in G. W. F. Hegel’s terms, to aufheben these twin questions (raise them to a higher level, taking seriously Albert Einstein’s warning that our main problems cannot be solved at the same level of thinking as the thinking that caused them).

If economic theory, like any scientific theory, is about which causes produce which effects, then questions about what will work to achieve the results desired are questions about economic theory. They are questions for empirical research and theoretical reflection. The framing of the research and the interpretation of the results are embedded in the theory.

A first observation concerning the question economic theory should answer—the question of what will work—concerns the claim in the EFF Manifesto that, according to heterodox economists,[40] nations that have successfully developed have succeeded because of state-led industrialization and because of protection of key home industries. We observe that there is no nation that has successfully developed, certainly not the countries named in the manifesto: Brazil, India, China, Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan and Finland. In fact, the modern world system is in crisis everywhere in the world. Further, there is certainly no relevant model for successful development if one thinks not of industrializing using yesterday’s technologies but of achieving social justice in harmony with nature, using tomorrow’s technologies.

A second observation concerning the question of what will work is that the ANC leaders during the freedom struggle believed that socialism (in some generic sense of that capacious term) would work, but by the time they became the government they had for the most part changed their minds. This second observation leads to our next topic, which is why the ANC backed away from a socialist reading of the Freedom Charter.

4. Mandela’s Choices

According to his authorized biography, at some point in 1992 Nelson Mandela called together his inner circle and said to them: ‘Chaps, we have to choose. We either keep nationalization and get no investment, or we modify our own attitude and get investment.’[41] A logical first response to this statement would be to say that Mandela was wrong: South Africa did not have to choose.

South Africa already had a large public sector, built largely by Afrikaners as a counterweight to Anglo economic supremacy, and if it had any difficulty in accessing international capital markets, such difficulty was because of moral condemnation of apartheid, not because financial institutions refused to lend to government-owned enterprises or to buy their bonds. Brazil’s state-run Petrobras has had no problems raising investment funds in capital markets or partnering with private-sector petroleum giants like British Petroleum. Indeed, Brazil´s experience in establishing a plastics industry was the opposite of what Mandela appears to assert: private capital was not willing to take the plunge until public capital had put up most of the money and assumed most of the risk.[42]

To be sure, ideological prejudice exists. When the American retail giant Walmart acquired the Chilean supermarket chain Lider, all products made in Cuba or Venezuela disappeared from Lider’s shelves. But for the most part, business is business. When an enterprise in any sector is profitable enough to pay the cost of capital at market rates, it can acquire capital.

This is especially true today, when the world is awash in accumulated funds unable to find productive use in the real economy. Today enormous sums find no better use than speculating in the ups and downs of currencies and other paper and electronic fictions in what has become known as the global casino economy. Today what John Maynard Keynes called a ‘liquidity trap’ has become the stuff of everyday life—as is shown in European countries where central banks have lowered interest rates to zero and still there is a shortage of entrepreneurs brave enough to take out loans. An enterprise in any sector with real resources producing real products for real customers holds the aces when playing poker with global investors. And for every Walmart there is an employee-controlled pension fund or an investors’ social responsibility fund somewhere in Europe or North America that positively prefers to invest in social and ecological progress and is happy to fund viable enterprises with worthy purposes in any sector.

Nevertheless, Mandela’s conversion to accommodating liberalism is understandable, and when he backtracked on socialism, he did not backtrack on his ideals. Instead he became an ardent advocate of human rights, chairing the writing of the world´s most progressive constitution, which guarantees a record 35 inalienable rights.

In 1990, when Mandela was released from jail, he told a cheering crowd in Cape Town during his first public appearance that he was still a loyal ANC member and that the Freedom Charter was still its programme. Two years later, he told his inner circle that they would have to modify their attitude to get investment. We can assume that what was going on in his mind from 1990 to 1992 was a gradual adjustment to a world and to an economic science that had changed while he was in prison. In 1993, he wrote as the first paragraph of an article he contributed to the American magazine Foreign Affairs:

As the 1980s drew to a close, I could not see much of the world from my prison cell, but I knew it was changing. There was little doubt in my mind that this would have a profound effect on my country, on the southern African region, and on the continent of which I am proud to be a citizen. Although this process of global change is far from complete, it is clear that all nations will have boldly to recast their nets if they are to reap any benefit from international affairs in the post–Cold War era.[43]

In the article, Mandela spells out how South Africa would join the ‘new world order’. By the early 1990s, the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc that might have supported a socialist South Africa had melted away. Social democracy was melting away in western Europe. In Sweden, which like the Soviet Union had faithfully supported the freedom struggle in South Africa, a conservative government had been elected after the world-famous Swedish model had proven to be unsustainable.[44] The proposition that socialism does not work appeared to have been demonstrated by historical experience. Neoliberal thinking was firmly entrenched in the governments of the world’s major powers, including those seated at Moscow, Beijing and Hanoi.[45] It was entrenched in the International Monetary Fund and at the World Bank, as well as in the World Trade Organization, which would soon meet in South Africa with Mandela as host. The neoliberals had the power. South Africa was largely constrained to play by their rules; in particular, it needed the 850-million-dollar emergency loan that the ANC had secretly negotiated with the IMF.[46]

In addition to the de facto power of the new neoliberal world order, by the 1990s academic neoliberal economists had been generating intellectually powerful theories supported by persuasive empirical findings for half a century, in the process generating a dozen Nobel Memorial Prizes in Economic Science. It seemed reasonable to believe their claims that minimal government and maximum free markets would bring employment to the unemployed, reduce inequality, and lift the poor out of poverty.[47] Their superficially plausible theories had not yet been refuted by tragic historical experience in South Africa and the rest of the world. It is easy, then, to understand why in the early 1990s Nelson Mandela and other ANC leaders put their faith in somewhat nuanced neoliberal ideas. It was a necessary accommodation to the perceived realities of economic and political power. It was a defensible intellectual judgment.

We suggest that one reason for the persistence of such ideas today is that even though neoliberal economics is discredited, the well-known alternatives to it have also been discredited. As we write this book in 2019, experience and thought are still in flux. The implausibility of neoliberalism does not prompt a return to Soviet-style central planning. Nor does it mean reviving the Western European style of social democracy that was dying in the late eighties and early nineties even as democracy was being born in South Africa. Rather, at this point in history a reconsideration of premises common to all three (central planning, social democracy and neoliberalism) is called for. We are being asked to reconsider what Joseph Schumpeter in his History of Economic Analysis named the ‘institutional frame’ of economics.[48]

Today the physical realities of ecology and the social realities of deepening structural unemployment, underemployment and precarious employment are happening off the blackboards of mainstream liberal economics in a space different from the Cartesian space of its curves. The breaching of the natural boundaries of the biosphere makes daily more poignant Kenneth Boulding’s remark that anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a lunatic or an economist. The onward march of technologies such as robotics, 3-D printers and artificial photosynthesis is consigning mainstream ideas like ‘full employment is normal’, ‘a natural rate of unemployment around five percent is normal’, and ‘investment (or growth or development) will bring an end to mass unemployment’ to the same lunatic category as the beliefs of flat-earthers, holocaust deniers, and global-warming deniers.[49] But a call to reconsider the institutional frame need not imply a free pass for dissident economists. Nor is it a call to revive without amendment the economic beliefs held by Nelson Mandela and his colleagues when they first set foot on Robben Island.

5. The National Development Plan

In February of 2010, President Jacob Zuma constituted a National Planning Commission to ‘take a broad, cross-cutting, independent and critical view of South Africa, to help define the South Africa we seek to achieve in 20 years’ time, and to map out a path to achieve those objectives’.[50] In June of 2011, the Commission released a diagnostic report, and in November of that year, it submitted a draft plan. Many thousands of people from all walks of life discussed the draft in meetings held throughout the country. In August of 2012, a widely owned revised version became South Africa’s official National Development Plan (NDP). We comment on a few of its key statements.

The plan draws extensively on the notion of capabilities. (NDP, Executive Summary)

The source of the notion of capabilities is Amartya Sen and his co-authors, Martha Nussbaum and Jean Dreze. Sen, Nussbaum and Dreze also emphasize pluralism—the idea that no one institution, in particular the market, and no two institutions, in particular the market and the state, can solve society’s problems. Sen wrote of ‘the mean streets and stunted lives that capitalism can generate, unless it is restrained and supplemented by other—often nonmarket—institutions’.[51] In this book we extend the idea of pluralism to the idea of unboundedness.

The source of the notion of capabilities is Amartya Sen and his co-authors, Martha Nussbaum and Jean Dreze. Sen, Nussbaum and Dreze also emphasize pluralism—the idea that no one institution, in particular the market, and no two institutions, in particular the market and the state, can solve society’s problems. Sen wrote of ‘the mean streets and stunted lives that capitalism can generate, unless it is restrained and supplemented by other—often nonmarket—institutions’.[51] In this book we extend the idea of pluralism to the idea of unboundedness.

The fragility of South Africa’s economy lies in the distorted pattern of ownership and economic exclusion created by apartheid policies. (NDP, ch. 3, ‘Economy and Employment’)

We show in chapter 2 of this book that every economy is fragile. There may or may not be investment. There may or may not be buyers. There may be—and sooner or later there always are—new technologies producing new products or producing the same products more cheaply, thus making whatever a person, firm or nation has to sell unmarketable. The phrase ‘community development’, when associated with unbounded organization, names ways to make people more secure in a world where purely economic relationships are always relationships at risk.[52]

Several studies, most notably Aghion and Fedderke, argued that profit margins are already very high in South Africa, even in the manufacturing sector. The high profits have not generated higher investment levels because many of these markets are highly concentrated with low levels of competition. (NDP, ch. 15, ‘Transforming Society and Uniting the Country’)

This statement implies a dubious scientific assertion: that if manufacturing in South Africa were more competitive than it is, there would be more economic activity. This assertion relies on theories that regard competitive markets as normal and normal markets as tending toward full employment of all factors of production.

We argue that such theories have never accurately portrayed the real world of business, and that, in any case, they will be useless in a high-tech future. Instead of making business more competitive, a better approach is to make business contribute more to society by generating a larger social surplus, and then to transfer the surplus to create more livelihoods that do not depend on sales. To this end, instead of sending high-powered promoters of South Africa to scour Wall Street and the city of London to find new investors and convince them that new businesses in new niches can be new sources of profit in South Africa, it is better to work hand-in-glove with enterprises that are already in South Africa—develop more transparent and ethical relationships with, and expect more contributions to the common good from, businesses that already have an emotional attachment to this long-suffering country and that have already proven themselves to be profitable here.

South Africa’s level of emissions will peak around 2025, and then stabilise. This transition will need to be achieved without hindering the country’s pursuit of its socioeconomic objectives. (NDP, ch. 5, ‘Transition to a Low Carbon Economy’)

There is no more graphic or poignant illustration of the clash of social structure with physical necessity than the struggle of South Africa’s planning commissioners to come to consensus on environmental policy. As the quote above reveals, their efforts ended in a nonconsensus prescribing an impossibility. As further evidence of the commissioners’ split opinions, chapter 4 of the NDP calls for a new rail corridor to the Waterberg coal fields and for generating more coal-fired electricity. Stabilising South Africa’s carbon dioxide emissions by 2025 is too low an objective, despite the objective stated here to reduce emissions.

The carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere is already over 400 ppm, which is too high, and experts tell us it cannot be stabilised short of 500 ppm, which is much too high. Nobody should be surprised if even the too-low goal of 500 in 2025 is not achieved. And nobody should be surprised that whatever South Africa does will be ineffective, since success would require concerted global action that included the large economies.

None of this is the fault of the NDP. Nor is it the fault of the commissioners or the South African government. It is the fault of the logic and dynamics of the economy, which in turn is the fault of the basic social structure, which in turn is the fault of history. As history has turned out, although it is physically possible to save the biosphere and with it the human species, it is not, as things now stand, socially possible. In this book, we are proposing unbounded organization as an approach to making socially possible what is physically possible.

Society is constrained by a socially constructed reality called economic reality, and the current economic reality is that human needs are met by a system that either runs on profit or does not run at all. Specifically, the commissioners could not, even if they wanted to, shut down a large privately owned business that brings money into South Africa by exporting coal to Asia. They knew this. We quote them: ‘Indeed, in the era of globalisation, is it possible for any government to be able to discipline capital?’ (ch. 15, p. 477). The NDP’s power, like the government’s power, does not extend to reversing the dynamics driving the self-destruction of Homo sapiens.

A footnote in chapter 1 of the NDP, ‘Key Drivers of Change’, includes a quote from Dani Rodrik’s book One Economics, Many Recipes[53]: ‘”You don’t understand; this reform will not work here because our entrepreneurs do not respond to price incentives,” is not a valid argument. “You don’t understand, this reform will not work here because credit constraints prevent our entrepreneurs from taking advantage of profit opportunities” or “because entrepreneurship is highly taxed at the margin,” is a valid argument’. Rodrik’s unabashedly neoclassical book was published in 2007, prior to the 2008 meltdown leading to the global recession that has continued. A few buildings away on the same Princeton campus where Rodrik works is the office of Paul Krugman, a Nobel Prize winner in economics. In his 2009 book The Return of Depression Economics, Krugman argues that whatever may happen on a practical level, on the level of economic theory, the series of crises in the last few decades, culminating in the 2008 meltdown, demonstrates that on some key issues the neoclassicals were wrong and the neo-Keynesians are right.[54]

In this book we criticize Rodrik (and his co-authors, Andres Velasco and Ricardo Hausmann) in some detail. Although theirs is the only mainstream book we critique, we mean our critique to apply to other books of the same genre, which we call ‘mainstream empirical studies’.[55] Such books compare the results of left-leaning and right-leaning economic policies. The weight of empirical evidence tends to favour right-leaning policies, in spite of the exceptional empirical counter-evidence cited by left-leaning economists. Our approach is to analyse the basic structural causes of the empirically observed relative success of, for example, lower wages, lower taxes on profits, less welfare and more austerity. Instead of concluding that right-leaning policies should as a general rule be adopted, we propose (and empirically illustrate the effectiveness of) transforming the basic social structure.

We hold that in the long run, and perhaps in the medium run, there can be no future for humanity or the biosphere without emancipation from the social structures that produce the anti-life results that are, unfortunately, currently observed. Emancipation so conceived does not require imposing on humanity an abstract totalitarian utopia. It does require an open-minded (unbounded) approach to economic theory, along with a psychologically effective and multicultural approach to ethics. A better theory will be capable of seeing—and a stronger ethics will be capable of actively supporting—the thousands of transformative social innovations already happening. Some achievements at some sites of South Africa’s Community Work Programme are among them.

While South Africa’s planning commissioners cite Rodrik’s hard-nosed semi-standard economics, they also appeal to sentimental patriotism. The NDP begins with a picture of children putting their hands together in a gesture of solidarity. It continues with a long lyrical prose-poem vision that celebrates the traditional African value of ubuntu. The NDP calls for social cohesion across society. It calls on both business and labour to moderate narrow self-interest for the sake of the greater good. Integral parts of the Plan are more psychological than economic. Children are to learn social values in school—on this point we could not agree more. A ‘Bill of Responsibilities’ is included in the Plan as a tool to change behaviour.

While South Africa’s planning commissioners cite Rodrik’s hard-nosed semi-standard economics, they also appeal to sentimental patriotism. The NDP begins with a picture of children putting their hands together in a gesture of solidarity. It continues with a long lyrical prose-poem vision that celebrates the traditional African value of ubuntu. The NDP calls for social cohesion across society. It calls on both business and labour to moderate narrow self-interest for the sake of the greater good. Integral parts of the Plan are more psychological than economic. Children are to learn social values in school—on this point we could not agree more. A ‘Bill of Responsibilities’ is included in the Plan as a tool to change behaviour.

Echoing the NDP, Adam Habib writes in an article on South Africa, ‘The successful consolidation of democracy requires . . . an expanding economic system within which resources are made available for redistribution, so as to lead to an appreciable increase in the standard of living of the populace.’[56] The opinion that higher economic growth is an indispensable prerequisite to higher employment and lower poverty is not only the opinion of the NDP commissioners, their academic advisors and, presumably, the thousands who participated in the planning process. A recent survey of public policy debates, reported in the South African media, concluded that it is an opinion nobody denies. The surveyor was himself surprised to find that, even though South Africa had its Economic Freedom Fighters and its share of left-leaning politicians, labour leaders and intellectuals, nobody—or at least nobody visible in the media—was offering an alternative to the standard International Monetary Fund prescription of investment to create growth and growth to create employment.[57] This prescription is implicit on every page of the NDP.

Nevertheless, chapter 1 of the NDP confesses that prospects for high levels of growth are not good for the foreseeable future. Every year so far, growth has been less than the NDP target of at least five percent. It was 2.8 percent in 2010, 3.1 percent in 2011, 3.9 percent in 2012, 4.4 percent in 2013, 1.5 percent in 2014, 1.3 percent in 2015, 0.3 percent in 2016, 1.3 percent in 2017 and 1.8 percent in 2018.[58] As we discuss later, Thomas Pikkety has made a convincing argument that, except for nations doing what he calls technological catch-up, slow growth will be the norm for the twenty-first century.[59]

In this book, we criticize the very concept of growth. With respect to growth, the famous words of Ludwig Wittgenstein apply: ‘A picture held us captive. And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably.’[60] Growth is commonly pictured as a larger pie to be sliced. We argue that there is no such pie and that if there were such a pie, there would be no one authorized to slice it. Instead of advocating no growth or degrowth, we advocate what we call governable growth.

We agree with the NDP’s call for the wise use of rents from natural resources. Rent is a major part of surplus. To use surplus wisely is to use it to meet needs in harmony with nature. However, we propose a different vocabulary expressing a viewpoint that reworks theory in the light of brute facts and on-the-ground working alternatives. A first step must be to face the question of how to eliminate poverty and how to reduce inequality under conditions of slow or no growth. We put community development forward as a big part of the answer to this question, and we put community broadly understood as, in principle, a complete answer. Later steps include critiquing GDP as a measure of growth.

Citizens have a responsibility to dissuade leaders from taking narrow, short-sighted and populist positions. (NDP, overview)

The term ‘populist’ denotes a pattern of tragedy all too common in the twentieth century.[61] Leaders seen as demagogues by some and as progressives by others win political power by promising a welfare state. To win and to keep power, they mobilize the masses. Ever more popular participation in politics leads to ever more demands on the state. Taxes go up. Wages go up. Capital flees. The state has assumed more burdens than it can carry. The leaders have made more promises than they can keep. The people come to feel that their leaders have betrayed them. The country is paralyzed by protests and strikes. Inflation makes wage increases illusory and business impossible. The dénouement is an authoritarian crackdown that persists until the authoritarian regime itself crumbles and the cycle begins again.

The NDP proposes in place of such a vicious cycle a virtuous circle. A social compact establishes the preconditions for economic growth. Economic growth makes it possible to fund a welfare state. The first principle of the social compact is the security of property rights, especially the property rights of the mine owners. With credible guarantees that there will be no nationalization, mine owners can invest with confidence. The requirement of a stable environment for economic growth is the reason why citizens have a responsibility to dissuade leaders from taking short-sighted populist positions. Populism chills growth because it chills confidence.

By the same token, as the NDP whispers and reality shouts, if economic growth leads not to welfare but to profits being taken out of South Africa and invested elsewhere, there will be no virtuous circle. Either populism or the socially irresponsible exercise of property rights can render the careful work of the commissioners vain.

In this context, we emphasize, the spectre of absolute conflict reappears. From a moral point of view, conservatives can argue that the legitimacy of any government depends on its respect for property rights. Progressives can argue that everyone who is born on this earth deserves a fair share of the gifts of nature (products of nobody’s labour) and the gifts of history (products of the labour of nobody now living), and sooner rather than later; the dispossessed have already waited too long to receive their rightful inheritance. While the NDP appeals to citizens to resist populism, its anti-populist appeal relies only slightly on a moral defence of property rights. It appeals much more to the human longing to be part of a social whole with a common purpose.

The NDP will inevitably be reconsidered. The numbers the commissioners projected as objectives for tomorrow will inevitably be replaced, one by one, by numerical descriptions of yesterday. It will always be possible to argue that the plan would have worked if only the masses had been less populist and if only the classes had been more socially responsible.

This book argues instead that any such plan cannot possibly work in the absence of a practical method for transforming the basic social structure. Unbounded organization is such a practical method. We argue that some things that South Africa’s Community Work Programme has been doing on the ground show how such a method works.

6. Economic Theory, Community Development and South Africa’s Community Work Programme

6. Economic Theory, Community Development and South Africa’s Community Work Programme

At this point, as Robert Frost wrote, two paths diverge in the woods, and we take the one less travelled. The more common path—the path of Spain’s Podemos party, of Jeremy Corbyn and Yanis Varoufakis, and of much of the South African left—calls a plan like the NDP neoliberal, even though its authors and its ideological mentors, Rodrik, Hausmann and Velasco, deny that they are neoliberals. And the common path of the left, quite rightly, calls for alternatives that are not neoliberal.

The problem, as we see it, is that these very alternatives have not worked in the past for reasons inherent in their basic structure. They are old and inadequate versions of democratic socialism. Typically, their goals in the South African context include nationalizing the mines, implementing the Freedom Charter, bringing the banking system or at least the Central Bank under democratic control, rebuilding a shattered welfare state, crafting an industrial policy where the state plays a leading role in accelerating development and so on. The political strategy for realising a not-neoliberal alternative usually calls for a broad-based coalition capable of achieving an electoral majority. It usually calls for exercising direct economic power through strikes, boycotts, cooperatives and worker-owned enterprises. It should be evident by now that this commonly travelled path regularly fails to arrive at its laudable goals.

Our less-travelled path treats the NDP and its mentors as a foil for rethinking basic economic theory and, moreover, as a foil for dissolving economic science altogether into a design science approach that does not separate constructing a world from understanding a world.[62] We view the failures so far of efforts to build democratic socialism as consequences of the basic cultural structure of modernity.[63] Changing policies, changing governments, changing who owns the means of production and changing economic models will not get Homo sapiens off the endangered species list unless such changes are accompanied by deeper intellectual and emotional changes that refocus humanity as a cultural animal. (We want to say ‘spiritual animal’, but we use that phrase only occasionally because for many it calls to mind exactly what we do not mean.)

At a practical level, we often agree with the common path. We agree with building an electoral majority, strikes, boycotts, cooperatives and worker-owned enterprises. We have participated in those activities, and we support them as long as they are accompanied by rethinking, redefining the problems, and unbounded organizing. We are intellectually convinced that the common path without rethinking, without doing what Fritz Schumacher called ‘inner work’ and without building a broad consensus will not work because we ourselves have experienced it as not working.

It is becoming more evident to more people every day that economic theory and community have to be rethought, or unthought, from the ground up. Our effort claims to be distinct from the many other rethinkings of economics on offer because (1) it reframes the issues in terms of social structure, and (2) it combines a conceptual study with an empirical study of a programme that (quite imperfectly) demonstrates in action some of the principles our rethinking advocates in theory. Unbounded organization, like Latin American economia solidaria, is a new theory that already has some practical achievements to its credit.

The empirical parts of this book examine one part of the public employment that South Africa’s National Development Plan called for: the creation of a million new jobs in public employment by 2015 and two million by 2030. This was to be done principally through the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP), of which the Community Work Programme (CWP) is a part. The following are some of the reasons why the CWP at its best has demonstrated the idea of unbounded organization in terms of practical experience:

1. The CWP partly succeeded in decentralizing a huge national programme by empowering grassroots citizen participation and partnering with local partners in many ways.

2. In the absence of social validation of the efficiency of resource allocation through sales in markets, and in the absence of a command economy with a Gosplan, the CWP found innovative ways to distinguish useful work from useless work.

3. Earning a dignified livelihood does not depend on selling or on complying with the requirements of a regime of accumulation.

4. The CWP seeks, in addition to the usual multiplier effect as money spent on public works is respent by its recipients, an additional kind of multiplier effect. It uses community development to mobilize resources complementary to those that can be mobilized through public budgets.

5. It has moved toward—though not yet to—an employment guarantee that would effectively insulate the right to a decent life from the vagaries of today’s labour market and from the virtual certainty that future technologies will make most work obsolete.

6. It achieved outcomes in social cohesion, and in mental health and a psychological sense of well-being, not achieved by social grants or less innovative forms of public employment.

[1] John Searle, The Construction of Social Reality (New York: Free Press, 1995); Joshua Rust, John Searle and the Construction of Social Reality (London: Continuum, 2006).

[2] Douglas Porpora, ‘Cultural Rules and Material Relations’, Sociological Theory, vol. 11 (1993), pp. 212–229.

[3] See Michel Foucault, La volonté de savoir (Paris: Gallimard, 1976).

[4] Willard van Orman Quine discusses Neurath’s Boat in Word and Object (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960).

[5] This point is brought out in ch. 2 and in the discussion of Say’s Law in ch. 9. It is fair to speculate that Adam Smith may have had a different view of natural liberty than did the people taken out of Africa as slaves at the time Smith was writing.

[6] See Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale (London: Zed Books, 1986); Catherine Hoppers and Howard Richards, Rethinking Thinking (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 2012).

[7] Heidegger’s plausible vocabulary is hard to translate, since so much of it depends on plays on words in German, such as eigen, Eigentum, eigentlich.

[8] Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit (Tubingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1986 (1926)), p. 149. Heidegger adds that every description is an interpretation.

[9] Roy Bhaskar, Reclaiming Reality (London: Routledge, 1989).

[10] Karl von Holdt, Malosa Langa, Sepetla Molapo, Nomfundo Magapi, Kindeza Ngubeni, Jacob Dlamini, and Adèle Kirsten, The Smoke That Calls: Insurgent Citizenship, Collective Violence, and the Struggle for a Place in the New South Africa (Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation and Society, Work and Development Institute, 2011). One of the cases studied, Bokftontein in North West Province, was a case in which a result of the Community Work Programme (CWP) preceded by an Organization Workshop (OW) was ‘. . . the end of intra-community violence and the deliberate rejection of xenophobic violence’ (p.3). The CWP, OWs, and the case of Bokfontein will be considered later in this book.

[11] Ibid., p. 6.

[12] Ibid., p. 15.

[13] Ibid., p. 15.

[14] Ibid., p. 16.

[15] Ibid., p. 21.

[16] Ibid., p. 23.

[17] Ibid., p. 27.

[18] Ibid., p. 34.

[19] Ibid., p. 23.

[20] See the studies of groups that articulate and mobilise popular discontent in Ted Robert Gurr, Why Men Rebel (Princeton University Press, 1970); and the references to ‘leaderships’ in Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (London: Verso, 2006), pp 160–161.

[21] Economic Freedom Fighters Founding Manifesto, (http://effighters.org.za/documents/economic-freedom-fighters-founding-manifesto/).

[22] Ibid., par. 16.

[23] Ibid., par. 30.

[24] Ibid., par. 31.

[25] Ibid., par. 36.

[26] Ibid., par. 137.

[27] Ibid., par. 33.

[28] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992). Fukuyama made an exception for certain countries that were ‘not yet’ capitalist democracies. He described them as ‘still in history’.

[29] Other documents of the EFF movement available on its website spell out details.

[30] EFF Manifesto, par. 35.

[31] Lewis Coser, The Functions of Conflict (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1956).

[32] Mfuniselwa J. Bhengu, Ubuntu: The Global Philosophy for Humankind (Cape Town: Lotsha Publications, 2006).

[33] Hoppers and Richards, Rethinking Thinking.

[34] Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale (London: Zed Books, 1986).

[35] For an Asian perspective see Howard Richards and Joanna Swanger, Gandhi and the Future of Economics (Lake Oswego, OR: World Dignity University Press, 2011). For a Latin American view see Gustavo Gutierrez, A Theology of Liberation (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1988). In the posthumously published Volume III of Capital (various editions), Karl Marx speaks of ‘gifts of nature’ which should not belong to any individual because they were not created by anybody, and of ‘gifts of history’ which should not belong to anybody now living because they were created by the labour of people now dead.

[36] Pope Francis I, Evangelii Gaudium (Rome: Tipografia Vaticana, 2013), pars. 188–89.

[37] Martin Heidegger, Sein und Zeit (Tubingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1986 (1926)), p. 149.

[38] Theodore Panayatou makes rational arguments for the ecological benefits of secure property rights in his Green Markets: the Economics of Sustainable Development, a copublication of the Harvard Institute for International Development and the Institute for Contemporary Studies (San Francisco, 1993).

[39] See Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better (London: Allen Lane, 2009) and other works by the same authors.

[40] The founding manifesto does not name any heterodox economists, but it may refer to the MERG report, proposals made from time to time by COSATU, and other technical studies that have been attacked and shelved in South Africa. See Matthew Kentridge, Turning the Tanker: The Economic Policy Debate in South Africa (Johannesburg: Centre for Policy Studies, 1993); and Hein Marais, South Africa Pushed to the Limit: the Political Economy of Change (London: Zed Books, 2011).

[41] Nelson Mandela quoted in Anthony Sampson, Mandela: The Authorized Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), p. 429.

[42] This and other similar experiences are documented in Cheryl Payer, The World Bank: A Critical Analysis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1982).

[43] Nelson Mandela, ‘South Africa´s Future Foreign Policy’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 72 (1993), pp. 86–97).

[44] See Assar Lindbeck et al., Turning Sweden Around (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994).

[45] Two important influences in Mandela´s conversion were his conversations with leaders from China and from Vietnam who told him of the acceptance of private enterprise in those Communist countries. ‘They changed my views altogether’, said Mandela (Sampson, Mandela: The Authorized Biography, pp. 210–211).

[46] John Saul and Patrick Bond, in South Africa: The Present as History (Woodbridge, UK: James Currey, 2014), give details on the power-politics aspects of the imposition of neoliberalism on South Africa.

[47] Such optimism is expressed in Milton Friedman´s now classic neoliberal text Capitalism and Freedom, published by University of Chicago Press in 1962. Similar claims were made for a reform package proposed by the South Africa Foundation in 1996. We do not think they could be made today. The history of these issues in South Africa is reviewed by Hein Marais in South Africa Pushed to the Limit.

[48] Joseph Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis (New York: Oxford University Press, 1954, p. 544).

[49] Bernard Stiegler, For a New Critique of Political Economy (New York: Wiley, 2010); Jeremy Rifkin, The Zero Marginal Cost Society (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). Rifkin’s point is not just that today’s new technologies make human labour increasingly redundant. It is that in principle the tendency to replace humans with machines and electronics is infinite with no end in sight.

[50] All quotations are from the plan itself and associated documents found at www.npconline.co.za.

[51] Amartya Sen, ‘Sraffa, Wittgenstein and Gramsci,’ Journal of Economic Literature. Volume 41 (2003), p. 1247. We will quote this line several times.

[52] See Ulrich Beck, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity (London: Sage, 1992).

[53] Dani Rodrik, One Economics, Many Recipes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).

[54] Paul Krugman, The Return of Depression Economics (New York: Norton, 2009).

[55] Other books of the mainstream empirical studies genre include David Neumark and William Wascher, Minimum Wages (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008); Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards, eds., The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991); and Alberto Alesina, Carlo Favero and Francesco Giavazzi, Austerity: When It Works and When It Doesn’t (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019).

[56] Adam Habib, South Africa: ’The Rainbow Nation and the Prospects for Consolidating Democracy’, African Journal of Political Science/Revue Africaine de Science Politique, vol. 2 (1997), p.19.

[57] Keith Boyd, Over the Rainbow: From Closed Circles to Virtuous Cycles (Unpublished MBA Dissertation, University of Cape Town, 2016), p. 40.

[58] Statistics South Africa Statistical Release P0441; and ‘World Bank: South Africa Country at a Glance’, www.Worldbank.org/en/country/South Africa. These numbers would be lower if they were expressed in terms of GDP per capita, thus taking into account the growth of population.

[59] Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2014).

[60] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations (Oxford: Blackwell, 1958), par. 115.

[61] Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards, eds., The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

[62] Herbert Simon, The Sciences of the Artificial ,3rd ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996). Unbounded organization can be viewed as a science and art of the artificial and also as practicing what Paulo Freire called ‘cultural action’.

[63] Howard Richards and Joanna Swanger, The Dilemmas of Social Democracies (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2006).

© Dr Howard Richards

Overview

Overview  Our situation, however, is even worse than that of Neurath’s sailors because, much more than the history of physics that Neurath mainly had in mind as his boat, the history of economics is a history of the construction of social realities. We claim that economic theory did not arise just to understand its object of study, i.e., modern economic society; it arose as part of the social construction of its object of study. Adam Smith was not just a student of market exchange; he was an advocate and an architect of a society under construction whose most powerful institution would become market exchange organized by the rule of law.