Live Encounters Magazine July 2021.

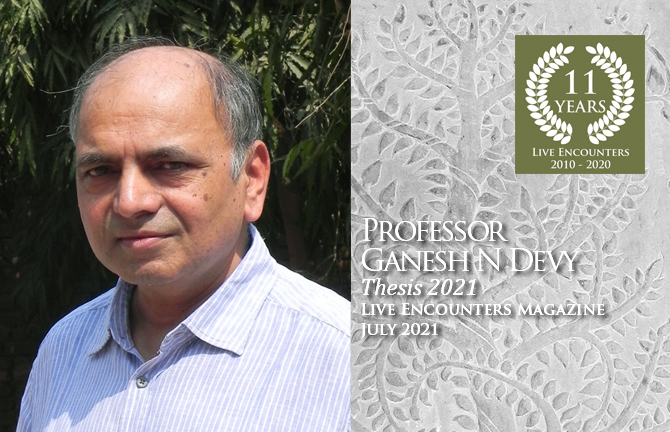

Professor G. N. Devy was educated at Shivaji University, Kolhapur and the University of Leeds, UK. He has been professor of English at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, a renowned literary critic, and a cultural activist, as well as founder of the Bhasha Research and Publication Centre at Baroda and the Adivasi Academy at Tejgadh. Among his many academic assignments, he has held the Commonwealth academic Exchange Fellowship, the Fulbright Fellowship, the T H B Symons Fellowship and the Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship. He was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award for After Amnesia, and the SAARC Writers’ Foundation Award for his work with denotified tribals. His Marathi book Vanaprasth has received six awards including the Durga Bhagwat memorial Award and the Maharashtra Foundation Award. Similarly, his Gujarati book Aadivaasi Jaane Chhe was given the Bhasha Sanman Award. He won the reputed Prince Claus Award (2003) awarded by the Prince Claus Fund for his work for the conservation of craft and the Linguapax Award of UNESCO (2011) for his work on the conservation of threatened languages. In January 2014, he was given the Padmashree by the Government of India. He has worked as an advisor to UNESCO on Intangible Heritage and the Government of India on Denotified and Nomadic Communities as well as non-scheduled languages. He has been an executive member of the Indian Council for Social science Research (ICSSR), and Board Member of Lalit Kala Akademi and Sahitya Akademi. He is also advisor to several non-governmental organizations in France and India. Recently, he carried out the first comprehensive linguistic survey since Independence, the People’s Linguistic Survey of India, with a team of 3000 volunteers and covering 780 living languages, which is to be published in 50 volumes containing 35000 pages. Devy’s books are published by Oxford University Press, Orient Blackswan, Penguin, Routledge, Sage among other publishers. His works are translated in French, Arabic, Chinese, German, Italian, Marathi, Gujarati, Telugu and Bangla. He lives in Dharwad, Karnataka, India. www.bhasharesearch.org

1

Power, at its best, is in the structure and form of an overwhelming rumour; at its worst, it is mimesis, but a copy of what has been power at some distant time in the past. For a rumour to be a rumour, there has to be a field for its spread, which, in this case, is the credulous audience. Mimesis, in order to be a credible mime asks for an as yet unforgotten precedence, something in the past that somehow worked. The credulous audience for power that is rumour needs to perceive itself as ‘one’ of some kind, of whatever kind, a state, a nation, a movement, anything that is capable of dynamism and not entirely in the grips of a stasis.

The perceived oneness of the credulous audience generates an intangible horizon of expectations. All those in this perceived ‘one’ entity know that the horizon is there, but no one can name it with any complete precision. Power at its highest brilliance lifts up the intangible horizon; at its lowest, it dips the intangible horizon.

Every change in the holder of power necessarily requires change, on part of the ‘audience’, in the perception of what power is and can be. The perception is nascent when such change is imminent; but change is impossible when the perception is closest to being sensed as delusion, not quite delusion but close enough to be seen as delusion. The perception of change is conditioned by the psychology of the perceivers, their political orientation and their tolerance to collective hallucination.

Therefore, in order to perpetuate power, those in power attempt to deepen the proclivity to hallucination that the ruled people have. Media, once seen as a pillar of democracy, is known to induce hallucination by a mix of not speaking, speaking and speaking out. When those who are in power are conservative, media prefers speaking over speaking out. In order to counter formation of such nexus, two methods become effective: Lifting the intangible horizon of people’s expectations in such a way that the rulers start losing nerve; and, Changing the goalposts between speaking and not speaking.

Media management is not the question of scale but of skill. It requires a deep understanding of what amounts to silence and what the horizon of expectations are. It requires acute ability to sense what silence is and how it relates to speaking.

2

Thinkers all over the world are seriously worried about the future of democracy, at least the kind of democracy that the world had dreamt of during the twentieth century. Similarly, there is an anxiety if the human control over large social and political systems can at all be continued in view of the great advancement in Artificial Intelligence. Central to both these large questions is the question of how we grasp the mutual engagement of democracy and machine memory.

Natural Memory, in order to be memory, first needs to predicate a notion of past. One does not know if the limitless expanse and emptiness through which the process of the creation of the cosmos and the subsequent process of evolution of life have progressed, can be attributed with a time dimension. But, having conceptualised Time and its segments such as the present and the non-present time, Memory likes to make an engagement with the past its prerogative. Having come into existence, Memory asserts its identity by striving to infinitely extend the past backward to an ever-receding point of origin. This it does, as Memory is a generative process, a lot more than it is a process of mere collection and record of what is or was. The idea of an infinite past, though a mere hypothesis, turns the ever receding pastness into ‘something’, a ‘that’ or an ‘it’ an object for curiosity, though such a pastness is only a hypothesis. The indescribable ‘it’, without attributes and without any further past is, then, imagined as power. In turn, it also begins to be seen as the source of all forms of power, spiritual or material, either in the order of God or in the order of Government.

For primitive human society, power emanated through the word of shamans, for it was the shaman alone who was believed to possess a superlative ability to remember all, something that the others did not have. In societies that accepted kingship as a valid form of power, the king was believed to have a kind of a divine sanction to rule and was believed to be the holder of memory of the precise moment of the birth of this arrangement. The King’s subject people were not considered worthy of such a divinely sanctioned ability.

The idea of democracy took birth in the desire to rebel against the idea of ‘That’, ‘It’, ‘the pastness beyond past’, and anything that was outside the reach of man’s rational abilities. Though the specific historical particulars differ from nation to nation, the desire for accepting democracy as the form of government has a shared universal narrative. It is a new social and political arrangement which is bound to have an uneasy relationship with a mystified and deified past. Besides, the historical moment of arrival of democracy as an arrangement of power, which coincided with the birth of rationality as the foundation of science and modernity as an eco-system of sensibility, place a further stress on the uneasy relationship between Memory and Democracy. For many centuries in the past, Utopia was seen as the mythical future. In the era of democracy, future ceases to be a mere myth and starts becoming the source of power, a function that memory had performed in pre-democratic ages.

3

It is difficult to say if the historical coincidence of the rise of rationality as the essence of knowledge and the rise of democracy as the essence of power-arrangement is reason enough to argue that the emergence of the technology driven non-natural memory is in any tangible way linked with democracy. Sigmund Freud’s analysis of dreams points to the working of suppressed natural memory as the mother of dreams. It is difficult to say if, in an analogues way, Artificial Memory, the AM or the memory chip, has an ability to spawn dreams of the future in the era of democracy. The AM is organised and systematic. Unlike natural memory, it does not predicate a past, and certainly not an interminable past. It does not mystify and deify that infinite past, which is essentially but an idea. The AM is self-sure and does not require for its self-justification the idea of a creator God, a long forgotten moment of its creation and a point of origin, albeit never to be fully known. The AM is itself its origin. It itself is god.

Democracy, with its attendant mental ecology of modernity and its uneasy relation with the idea of the past does not easily grasp how it can deal with Artificial Memory. While it requires the future as a myth, it does not know how it can generate that myth in the times of AM. That is going to be a long struggle and an entrenched debate that human societies will have to negotiate in the decades to come. Meanwhile, the AM, which by its very condition of being what it is, neither being able to generate myth nor able to give birth to dreams, can only produce rumours, illusions, hypnotising chimera or mesmerising terror. Short of dreams— as distinct from rumours and illusions– for the future, the democratic order will continue to limp forward unless humans think seriously of the implications of the disjuncture between dreams and AM.

At present, most governments in the world, including the government of India, is over- busy using the AM to discipline order and control citizens. In that process, they are facilitating the supremacy of the AM over democracy. It is, however, too late in history to think of knowledge and society without an overwhelming presence of the AM. In the twenty-first century, democracy can redeem itself not by seeking to extend the grip of technology over psychology, not by calling to aid the ‘inner strength’ of democracy. That has faded out a few decades ago, not just in India but in most other countries.

Democracy can, and one hopes will, redeem itself not by an obsolete mystification of history and memory. It can be redeemed by grasping the absolute contradiction between Natural Memory and Artificial Memory. The party that is obsessively interested in making ‘past alone’ as the main plank of its politics is quite hopelessly out of tune with the historical shifts in the trajectory of memory and its impact on the forms of government. Similarly, politics which is entirely technology driven has a view of the future that can only hasten the decline of democracy. In the 21st century, the pro-democratic politics will have to bring gods and robots face to face and confront one with the other in order to rebuild the future as a myth and invent AM that is capable of a sense of its past. They need to meet and transform themselves for a long continued life of democracy.

The virtual world has posed an unprecedented challenge to our known ideas of space and time. It is over-busy providing legitimacy to non-matter as Real and Existent and reducing the material into incompletely existent. Citizens,therefore,cannot any longer be citizens unless they are in digital form free-floating in virtual time and space. And, because they are substantially digital, the idea of equality no longer is found relevant to sizing them.

4

Political energy, applied in the past by visionary thinkers and mass leaders to bringing citizen and citizen within a single matrix of class, race, gender, is not compatible to a society which understands no difference— while it materially exists but digitally disappears from view— and has yet not been replaced by new forms of political energy and transformative visions. The visions we see as transformative today are bogged down with a burden of dry numbers, data-sheets, graphs and a narrative related to numbered bodies and have no space for views and perspective that measure distance comparatively and progress in broken lines of the local and personal aspirations. Identity politics, therefore, can no longer be the driving engine for any movement that seeks to transcend the narrowness of identities. The society depicted in digits fails to grasp what is narrow and what is not.

Nation, in its earliest form, was the people. Nation, in its subsequent ideological forms, became the past of a people and the future of the people. The past imagined as a being spread over a very long span of time becomes challenge to memory and begins acquiring the form of myth, which is irrationally compressed and imaginatively transformed time. The future, as against the past, spread over an endless time, becomes a challenge to imagination and acquires the form of fantasy or utopia, which are compressed and fantasy driven re-statements of the idea of time. Therefore, a nation can live in real time only when it has a range of myths recognised by the people as their own and a fantasy or utopia owned by the people as of their own making.

5

Artificial Memory lacks – at least so far—the myth making ability. However, the technology based image making (imagination) is surfeit with fantasy.

In any tussle between the ideas of democracy inherited from the 20th century and the emergent ideas of democracy in the 21st century, the ideas of nation will undergo a radical shift. Those ideas will attempt to subvert the mythical and try to mould them in the form of fantasy.

In real time, fantasy cannot endure if it is entirely alienated from myth. How can the future tense in any language function effectively unless that language has a sense of the past tense structures; as with languages, so with political discourse. Therefore, in real time, merely technology driven power structures can but generate inadequate expression of the self of the people, the nation. It generally slips off the fantasy –terrain that it uses pervasively as the statement of its rational for being what it is. However, such power structures will not be able to return to their origins and earlier forms since history is a one-way traffic and irreversible.

The way forward, the only way forward, for the technology driven powers is to surrender to the idea of nation as its people; but, ironically, at that point in historical time when such an idea of nation will have been exhausted. The other alternative before such powers is to move in the direction of dissolving the idea of nation by generating a counter-narrative. The future for the people world over is to move in the direction of opening the possibility of rescuing the world from the idea of nation as people. It is within that paradoxical possibility that the new battle lines have to be drawn by those who do not wish to remain bound by over-used and out-dated political jargon.

6

‘Class consciousness’, a term widely used by Social Sciences, though useful in the times when it first began to be used, appears now to deny micro-specificities. Consciousness, in its intelligible form, is an attribute of an individual. It is predicated upon existence of life defined in terms of functioning of an individual’s brain. A given ‘class’, in its form as a group, cannot be said to have life of the same order as individuals in that group have. In the context of a large group, the term consciousness at best can be used as a metaphor. What a group does as action can at best be described as engagement and an intellectual and emotional investment for inter-subjectivity. Yet, under no circumstances, that can be described as ‘life.’ The class consciousness is essentially a metaphor useful for developing an argument and a narrative.

Historians, challenged by the complexity of their subject, take recourse to this metaphor. Social analysts use it only when viewing their subject from a distance. As soon as either of them get closer to the subject for finer analysis, what initially appears as ‘class’ starts appearing like a basket full of contradictions, paradoxes, a set of sub-classes and even as a throng of individuals. As such, the use of the term ‘class consciousness’ unmistakably signals procedural and disciplinary limits in its analysis. The metaphor acquires meaning only in the presence of its antonym which, in this case, is not ‘non-class’ or ‘classlessness’ but ‘some other class’. However, on scrutiny, the antonym too is seen to face exactly the same difficulty for it to be useful for a sound analysis. The idea of ’class’ has its historical roots in education system(s), as it is born in a ‘class room’. Independently, it has its roots in economics of want and denial. Yet, what is denial is a question, answer to which may fluctuate from age to another age.

Caste is an identity that individuals, at least in India, acquire passively. No individual has the control over the caste group within which she or he is born; though a few try to consciously transcend it of their own volition. In either case, the caste experience, being a lived experience, is less abstract than the class-experience. However, the caste consciousness is not any consciousness; it is the naming of the identity association experienced by an individual.

7

Federalism is natural if nature has brought together vast territories and kept them together through mutual interdependence. Federations which have diverse ecological conditions, may tend to stay together for a long historical period. Federalism resulting out of conquests of other nations by a given nation stay in place so long as the force that conquered those states continues to be adequately forceful. The former USSR collapsed because the conquered entities were ‘nations’ in and by themselves and their explicit or tacit consent to be ruled was missing during the process of forming the federation.

Federations born out of a gradually evolving entity can be lasting provided the sense of identity of its individual units is not overtly ethnic or linguistic. If the identity acquires primacy, such a federation becomes less than convincing, as has happened in the case of the European Union. The Indian federation is not entirely territorial or natural. It is not a creature of a conquest. It is not as fragile as the European Union is. What then is the catalyst for the federation that India is? Several waves of population settling down slowly over long stretches of history, creating different languages is one pillar of the Indian federation. Immense geographical and climatic diversity causing the emergence of distinct cultural zones is the second pillar of the Indian federation.

Governments in India that ignore the historical and geographical context of India’s formation can be detrimental to Indian federalism. In other words, when Indian governments attempt to overwhelm the Indian federation, India’s federalism moves towards centripetal dynamics and the federation can turn fragile and shaky. Cultural diversity, ecological diversity and linguistic diversity become less self-sure in times of any despotic regime. If the regime starts posing nationalism as an alternative to federalism, the unity of India comes under a tremendous stress. Therefore, a totalitarian regime can be challenged by highlighting India’s diversity, pluralism and its intrinsic federalism.

8

Power, which constitutes the entire spectrum of the dominated and the dominators, requires, in order to be constituted in that manner, the consent of the dominated for such an arrangement. As a scientific field of study, Psychology looks at the desire to be dominated as a mental abnormality. It also interprets the desire to dominate as an abnormality. Together they form a continuum of illness. Were such an abnormality to become the norm itself, it would require a collective effort for its concealment so that no one calls it an abnormality. Various methods of concealing it used in the past and the present have taken the form of rituals. All and every ritual associated with all and every form of domination is an attempt to conceal the widespread mental illness and turning what is essentially an abnormality into a norm. In democracy, representation of people is an ideal and a dream; but the processes formalised to actualise the ideal slip off the ideal. In course of time, the formalisation intended to effect the ideal ends up as a ritual. As the gap between the ideal and the ritual increases, representation gets replaced by covert or overt domination. Primarily empty rituals replace the relation between the represented and those who are supposed to represent them. Though it may look logical that if these rituals are unmasked, debunked and somehow made irrelevant, society may manage to return to the original arrangement born as an ideal. However, that logic has a deep flaw in it; such an assault on rituals of presentation may weaken those rituals as well as the ideal that they purport to embody. In the process the idea of democracy itself may suffer a wound impossible to heal. Recovery of democracy is possible not by attacking the aberrations that have entered it but by reasserting the original idea. Mixing the two—attacking rituals and affirmation of the ideal — can only perpetuate the mental illness that the spectrum of domination has been.

9

Every manner of reassertion of democracy needs to question not how people are represented but by foregrounding what people want represented. Therefore, the business of the civil society should be not exposing the aberrations but restating the dream, not trying to clean the ground sullied by the devious rituals but by lifting people’s sight to new and higher horizons of expectations. This task is very different from the task assigned by Karl Marx to the class capable of becoming society’s critical consciousness. In fact, the task cannot be performed by a class; it can be performed by individuals who refuse to be any class. Reinvention of democracy calls for public intellectuals who can place themselves outside class, race, and gender and, most of all, the momentary rush of events of the day.

10

Power can become active only through an implicit or explicit consent of the ruled, even if the consent is expressed through a mere ritual, optically correct but semantically distorted; In exceptional cases, power receives its sanction by inventing a platform or a modality making such the expression of such consent irrelevant. During the 20th century, the source of validation of power used to come from the following:

a. Constitutions, democratic, dictatorial, or mixed

b. No constitutions at all, if a venerated convention has been in existence for long

c. Military invasion of a country and a tacit acceptance of it by the community of nations.

d. Military or civil coup by a group within a given nation

e. Sudden revolution by people driven by an incipient ideology or a regime-fatigue.

f. The rise of an economic class or theological group claiming being majority

Several large scale political changes in the world over the last three decades indicate the rise of some previously unknown modes of regime change:

a) A sudden ecological disaster, climate change or other natural calamity

b) Overpowering of people’s natural intelligence by use of artificial intelligence

c) Use of biological weapons, internally or externally.

Given the above, the probability range for control of power during the 2020s—at least till the Indian population reaches its peak and starts declining — includes the following:

a. Constitutional Democracy

b. Constitutional Dictatorship

c. Religious Majoritarianism

d. Technology based control of citizens’ sensibilities

e. Focusing on Climate Change and Ecological Challenges

All other modes such as Satyagraha/ Movements, etc. are clearly improbable or self-defeating.

11

The present regime in India has been employing a combination of three of the above modes, in order of their effectiveness, in order to wield power: A. Technological control, B. Religious majoritarianism, and C. Constitutional Democracy

The BJP government in Delhi is still not fully equipped to scrap the present constitution due to its not having absolute majority in the Rajya Sabha. Therefore, holding one more general elections is an unavoidable compulsion for the BJP. Opposition parties are not in a position to fully counter and defeat the BJP for several reasons. The chief among these is that they operate within a relatively narrower range of probabilities. Therefore, the objective of the opposition parties should be ideally to restrict the BJP to less than two thirds seats in the Parliament, which can give it an absolute majority necessary for major constitutional amendments. The civil society needs to focus on resisting BJP’s technological superiority. The critical class of opinion makers have to reconstruct and redesign the sensibilities of the majority community and reduce its theological inclinations. Yet, all of these to happen, when they should happen, is a big challenge.

12

The movement of Europeans towards the world outside Europe began at the time when the hold of Catholic religion was beginning to decline. The rise of colonialism and the rise of Protestant movement not only just coincided, but they were also interconnected. The rise of science based on rationality and the decline of the idea of omniscient god were not just historically simultaneous but were also deeply interconnected. What colonialism found in the colonies was material wealth which European powers decided to drain. In return, the European powers transported to the colonies many things including some elements that were becoming out dated in Europe, mainly the church and ideas of divinity. Colonialism, from the perspective of Europeans, had objectives related to material wealth and emerged in the context of material deficit. Colonialism placed in circulation an over-inflated idea of spirituality of the colonies. However, nothing in the political, social and cultural life in the colonies during the 17th and 18th century indicated an overwhelming spiritual and theological life. Yet, the colonies responded to the colonial image of their self and imbibed a hallucinatory self-image as a spring of religious profundity in turn, imagining the long discarded theological schools as the core of their being. Hinduism, a large scale fiction, is a colonial product of this nature. It is in the manner of consoling the colonies for the material deficit being exported by the colonialist to their subject colonies. Several visions of the future were produced during the 19th century and the 20th century. It is a matter of discussion if any of them had the vision of India’s future as a materially prosperous country. The dominant philosophical influences in India during these two centuries were primarily social and humanistic and not political-economic. In order to reverse this history, India will have to re-enact the theatre that was enacted in Europe in the early phase of colonialism. By implication, any and every philosophy that harps on India’s religious character will necessarily generate lack of engagement with the material and the economic.

13

Twice in recent history religion centre BJP attempted to project itself as economically super competent government. In both attempts, the adventurism failed. Shining India could not be sufficiently convincing for the voters; and ‘sabka vikas’ has hardly been the main core of the Modi regime. The deep inter-relation between the material deficit on the one hand and over-statement of spirituality explicitly positioned in political sphere by the RSS-BJP on the other hand has an unmistakable stamp of the colonial legacy on it.

14

The widening middle class in India is not entirely a product of increase in the income levels of its citizens. It is also in a large measure the result of the food sufficiency and textile sufficiency that India attained for a while. It created a population not exactly rich but, at the same time, not exactly poor and, therefore, resembling middle classes elsewhere, yet not in material facts quite the middle class as seen through the lens of social analysts. The upper layer in the wide spectrum of the ‘middle’ class in India is not given to over-statement of its religious identity, though it is deeply attached to various theological sects and practices. The lower section of the ‘middle’ class is indeed ready to place theological identity among its ways and means of attaining prosperity. Science, but mainly technology, and material wealth are the primary interests of the upper layer. Therefore, they feel easily attracted to the neo-liberal economic order and the benefits it brings to them. The lower level middle class is interested in the public affirmation of theological identity in order to achieve up gradation in the social hierarchy ( what is called Sanskritization) and the potential benefits it may bring to them in future.

Any political formation keeping the middle class in focus involves the risk of generating in the long run a clash and conflict between science-technology on the one hand and identity and theology on the other hand. This cannot be avoided in politics shaped from the perspective of the right wing-middle-class-majoritarian democracy.

15

In the corona induced economic down turn, the OBCs now in the lower section of the middle class are likely to begin to pass on the burden of keeping alive religion as a political argument to the poorer and pauperised classes, tribals, migrant labourers, farmers, the unemployed youth and housewives whose families are destroyed by the pandemic. The OBCs are likely to shift their political loyalties towards theologically non-explicit and materially and technologically more explicit politics, the politics that demands wider spread and access to education and healthcare. The aspiring OBC class, therefore, will come in a clash with the upper layer of the middle class. Those who desire to dismantle the right wing regime in India will have to work on the cross-section of the OBCs and the upper classes, and at the same time taking science and technology to the poorer classes.

16

The beginning of the year 2000 had brought great excitement among people in all continents. That was the year marking the beginning not just of a new century but a new millennium. Many names were suggested as historical tags for the new century; but probably the one that was received with the greatest enthusiasm for the 21st century was ‘the knowledge century’. Two decades is not such a long span of time; but time, indeed, has humbled humans, for no one talks of the present century now using that term. The world has meekly accepted to look askance at what is in store for homo-sapiens. At this juncture, the future looks so embattled. We are surrounded by so many newly unfolding war-fronts.

There are news-reports about a strange war that appeared in several newspapers in Karnataka last month. These reports covered an on-going war between elephants and humans. Some 800 elephants roaming in what is known as the ‘elephant corridor’ of the Western Ghats have opened a systematic war with the human habitants there. It has been recorded by the forest officials since 2014. During it so many humans have been maimed by elephants and so many elephants have been shot dead. The tension between the two warring sides is so acute that the forest officials in the Hasan District have decided to install censors for alerting the inhabitants to the presence of elephants in the vicinity. A siren starts sounding when these censors pick up elephant presence and humans run to the nearest safe-shelter reminding one of Londoners getting into tube stations when Hitler’s military planes hovered over the city during the Second World War. Just a month before the news about the elephants in the forests in India came, one had read about the outburst of bush-forest fires in Australia. The geographic spread and the frequency with which those fires erupted were mind-boggling. They spread over nearly 110,000 sq kms and had in a single week caused the death of 33 persons. The sheer number of trees destroyed by these wanton fires runs into millions. Australia is not the only continent where forest fires have besieged humans. North and South Americas, East Africa and South –East Asia have witnessed increase in the frequency with which forests are getting gulped by uncontrollable wild fires.

17

A Harvard Professor of Astronomy Avi Loeb claimed earlier this year that the floating object spotted in the outer space in 2017 was not natural but launched by another intelligent species. In his provocative book published in February Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth, Loeb warned the world that to not take the existence of an alien extra-terrestrial species seriously could prove a fatal mistake for us. The object he discusses is given the name ‘Oumuamua’, a word from the language of an indigenous community. Leob’s argument is that the orbit through which the object moved did not follow the laws of gravitation. It clearly showed that a ‘non-gravitational force’ was directing its movements. He believes that it is a spaceship powered by solar power generated by using hugh mirrors set on its body. His conclusion is the existence of extra-terrestrial aliens, a subject for science fiction and movies, can no more be seen as just a figment of imagination or fantasy. Another Professor has brought in even more disconcerting news for humans. Professor Idam Segev of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and his team of scientists are busy forming artificial human-brain cells. His research will feed into placing the intelligent machines at par with the most innovative humans. Combined with the rampant use by State powers of artificial intelligence for surveillance, the scientific advancement visualised by the researchers in Israel, unfolds before us the spectre of having a mix of intelligent machines and humans as the ‘ruling class’ in the coming decades.

The Corona virus disease spell has made the shortage of oxygen for medical purposes big news. But, just before the outbreak of COVID, we had seen that schools in Delhi had to be locked down as there was not enough oxygen in air for children to breathe freely. Air pollution at an alarming level is no longer news for any part of the world. But before the big economies of the world find a solution to this seemingly irreversible problem, David Beasley of the World Food Organisation has given a stern warning that over 83 cr people in the world, that is one in every ten humans, have entirely lost their food security. Already agriculture and fishing as conventional methods of food production have become entirely unviable livelihood choices for the generation born in the twenty-first century. The utter disregard of the Indian government for the farmers’ discontent is not just an expression of its characteristic arrogance. It is also, to an extent, a reflection on how low agriculture now ranks in the economic policies of governments.

What do these apparently diverse calamities threatening human existence indicate? Whether arising out of threats posed by microscopic viruses, radical environmental changes, artificial intelligence, extra-terrestrial interference or out of sheer human arrogance towards nature, indifference to suffering of fellow humans and insensitivity to the signs of the resulting degeneration, the nature of wars that humans have to face and fight in near future will be such that humans have never known in the past. The wars fought by us centuries ago, at the beginning of the second millennium, were mostly faith-based. They were crusades or jihads. The wars fought during the nineteenth century were nationalistic in character, based in ethnicity, language and contested territorial claims. The wars fought during the last century were driven by ideologies combined with economic interests, whether they were wars caused by Fascism, Communism or Capitalism. The wars waiting for us on the horizon are of a different character and a different order. These will be wars for or with environment, with the forces of the natural evolution, with non-human intelligence and with life and objects that belong to a different framework of matter and motion. Sadly, governments that humans have are still in the old world mind-set, prisoners of terribly dated political ideologies analysis focused on faith-based divisions, territorial contestations and narrow nationalism. Though the proponents of Cosmo-Democracy have made a beginning of thinking about political systems necessary for equipping humans to fight these new wars, their voice is still very feeble and has not reached beyond a very small circle of political scientists. But, time is ticking fast.

18

On all horizons in view there are unprecedented wars waiting for us. It is now for humans as a single species to unite, learn adaptation, respect the logic of evolution and manage to survive; COVID and much beyond it through this war century. In India we have the great task at hand of cleansing the minds of people of the poison of communal hatred spread by the RSS. We have also to bring in a government that is sensitive to people’s needs and perceptions. We have to think of how our federal structure can be given the centrality it deserves and the idea of India as a plural and diverse society can be safeguarded. We have to work towards restoring the institutions that secure democratic checks and balances in the system. We have to make education and basic health-care accessible to everyone as their fundamental right. We have to see to it that the media regains its freedom. And, we have to ensure an equitable livelihood opportunity to those whose economic condition deserves urgent attention by the state. Most of all, giving women the rights that legitimately belong to them is an urgent obligation on all of us. These are big challenges. There are equally big challenges posed by the non-human world. Protection of natural environment and keeping ecological balance are the foremost among them. Protecting individual privacy and dignity in the face of the vast advent in the field of artificial memory and artificial intelligence is also as daunting a challenge.

19.

During Margaret Thatcher’s regime, the conservative British habits of mind made England believe that would be some let up in the government’s anti-poor policies. That has not happened during the last four decades. After the dismantling of the former USSR, many had hoped that Russia would actually become a welfare state prompted by an open society. That hope is dead a good quarter of a century. An economically compounded Europe was initially seen as the transformed future of the nation state, and the brief spell of Euro-Communism was seen as rebirth of the idea of equality. Far from it, at present nearly a dozen European countries are experiencing a rapid rise of the political right-wing influence. One had hoped that long wars in Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan would end by generating new models of balance of power. Instead, they resulted in spawning the ugly face of militant theocracies and a range of non-state formations thriving on terror and violence. The world today looks more sordid, far more terrifying and unsettled than ever before. The sphere of influence of ideas of peace, amity, evenly shared progress, reason, balance and restrain has been continuously shrinking. It is as if, like the great economic depression forming the prelude to the second-world-war, there is a kind of a great political depression presenting itself to the community of nations as a prelude for something terrible to come.

The nineteen-eighties had brought to the world a fleeting vision of a one-world phase of the community of nations. Increased food sufficiency, better transport and oil tracking, more easily accessible healthcare and the promise of free flow of information were in the background of the German unification. In our country, those years were marked with the telecom and TV revolution. Despotic rules and dictatorships, where they existed, had started looking like expired ideas by mid-eighties. Liberal economic ideas were becoming ready to free the spirit of enterprise and creativity and loosen the stifling regimes making them supple and flexible. The fear of nuclear wars had started evaporating like some forgotten nightmare. The world thought that the future wars would be wars on malnutrition, disease and illiteracy. International agencies were getting ready to spell out their agendas for the Millennium Development Goals and ‘X for All’ kind of collaborative programmes. However, through the last three decades the mood has changed, changed altogether, and as w. B. Yeats said a century ago, ‘a terrible beauty is born.’

There is a cryptic definition of democracy which wits ‘democracy is a rumour not as yet disproved.’ In our time, it is indeed becoming only a rumour, in Chile, Russia, U.S.A., Nigeria, Egypt and even in our dear own country. During the last few years, world over there is an inexplicable rise of an anti-democratic sentiment. This is explained by thinkers with a left leaning as the capture of the state by the corporate. Gandhians explain this as a predictable consequence of unchecked greed. The neo-liberals explain this as a passing phase of the clash between technocratic ethics – ‘transparency’ and ‘fast-growth’– and the political order prone to ‘populist’ economic drives. There are also explanations stressing on the deviant personality traits of individuals, whether Donald Trump, Recep Erdogan or Narendra Modi. What is difficult to explain is why so many of them and all at one time? George Santayana had described his times as the world ‘on a moral holiday’. Following him, one can probably say that the world today appears to be ‘on a political holiday.’

20.

It is time for us to return from our political holiday, time to unmask the system, free it from the rituals that have replaced democracy and people’s representation and time to face the challenges head on. It is time for us to understand that humans have to come to terms with artificial intelligence, on the one hand, and with non-human life on our planet, and even beyond on the other hand. It is time for us to rethink and revitalise the idea of democracy, as an integral part of the global and even the cosmic arrangement of life. Cosmo-democracy is the term being used for such an arrangement. It is time for us to think of rights beyond the rights just of the majority, just of adults and just of humans. We need to invent ways of respecting and protecting the rights of all marginal communities and all minorities in every country, the rights of children and the rights of non-human life among all species in the world known to us and in the worlds that we still do not know but may come to know in near future, and also the rights of what is still not life—such as the AI– but is fast moving towards acquiring life.

In order to meet these challenges squarely, we need to come together on the following points:

1. Our political vocabulary is hopelessly outdated

2. Our political understanding can never be complete unless it integrates with a scientific view of the vast cosmos that surrounds us. It cannot be complete unless it takes into account life other than human life.

3. Systems so far created by us have remained lop-sided because they have not fully found out the ways of dealing with diversities and pluralities

4. We cannot bring about any fundamental change unless we propose for ourselves and adopt a working system of global governance, not as a community of nations but as a community of peoples, communities and cultures.

5. Democracy is a gift given to us by the previous generations of thinkers and leaders. We shall have squandered it away if we do not leverage it for moving forward to an idea of cosmocracy.

6. Politics is not about gaining or consolidating power but about gaining freedom for all from the bondage of outdated thought, slavery to a narrow identity and loyalty to sinking horizons of hope and expectations. Our job is to lift up those horizons.

© Professor Ganesh N Devy